Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door (21 page)

Read Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door Online

Authors: Roy Wenzl,Tim Potter,L. Kelly,Hurst Laviana

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Serial murderers, #Biography, #Social Science, #Murder, #Biography & Autobiography, #Serial Murders, #Serial Murder Investigation, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Case studies, #Serial Killers, #Serial Murders - Kansas - Wichita, #Serial Murder Investigation - Kansas - Wichita, #Kansas, #Wichita, #Rader; Dennis, #Serial Murderers - Kansas - Wichita

“No no no,” Landwehr said coolly. “Just follow your chain of evidence and let your case speak for itself. Don’t ever worry about anything else.”

Otis’s case held up.

“Landwehr, ever since I’ve known him, has had this steely-eyed confidence that we’re going to win our cases,” Relph said later. “He gets us that way because he knows how to build a case.”

They usually won, but not every time. Relph once saw a man he had investigated walk away with an acquittal. It horrified him.

To his relief, Landwehr stood by him all the way.

“Here’s where detectives get themselves lost,” Landwehr told Relph the day they first talked about BTK. “They get lost in some guy’s story. A guy looks good as a suspect; if you have maybe twelve criteria for being the right guy for the crime, and this guy meets ten of the twelve, then he’s looking good. And so the detective gets enthralled, chases his story�and goes off on a tangent, a wild-goose chase. Because if the guy’s DNA doesn’t match the DNA from the crime, it’s not him. And then you have to drop him like a rock.”

Relph began to apply this advice while reading about BTK and working on other cases.

“How do you not get lost in all these thousands of pages of evidence?” Relph asked.

“Don’t try to get into all that peripheral evidence,” Landwehr said. “Just read the actual case files. Focus on the essentials.”

That advice worked with BTK and with every new homicide Relph handled.

He realized, with some pride, that Landwehr had helped him become a better detective. And if BTK ever resurfaced, Relph would be ready to help Landwehr put him in a cage.

In the Landwehr house in Wichita there is a photograph that Cindy sometimes shows to family and friends. It shows the back of a man’s head and a baby reaching a tiny hand to the man’s face. The face is turned away from the camera, but anyone familiar with the family would recognize the narrow head and thick, dark hair of the chief homicide investigator for the Wichita police.

The boy was born in 1996.

Ken Landwehr had thrown himself into fatherhood with enthusiasm even before he became a father. Cindy had worked with special-needs kids for years and had talked Landwehr into becoming a foster parent with her. In the first three years of their marriage they served as temporary foster parents to ten children. That’s how they found the baby they wanted to adopt. They named him James.

Cindy had worried�most men want their own children, but she could not give Landwehr any. He waved off her concern. “That doesn’t bother me at all,” he said.

He was now responsible for shaping a child’s life. He soon saw that the boy was changing his life too. The Party Guy from Hell now stayed home changing diapers.

In that same year Bill Hirschman, working at the

Sun-Sentinel

in Florida, heard that a fellow reporter was leaving for

The Wichita Eagle

. Hirschman met him for coffee. Roy Wenzl, a Kansas native, was anxious to move home. At the

Eagle

, Wenzl would join the newspaper’s crime team, Hirschman’s old group. Hirschman was delighted. He had spent fifteen years at the

Eagle

and became almost weepy talking about Wichita and Kansas and people he missed.

You will work with Hurst Laviana, he said. He’s a resourceful investigative reporter. Wichita is a much safer place to raise children, more neighborly and relaxed, much friendlier than South Florida, Hirschman told Wenzl. There’s some crime, he said, and of course there is BTK, the big one that never got solved. Some people think he’s dead, Hirschman said. Or in prison. But he and Laviana thought BTK may have just quit killing.

Maybe BTK will never be solved, he said.

Wenzl looked puzzled.

“Bill,” he said. “What’s a BTK?”

A year later, at the

Eagle

, Laviana told Wenzl the whole story. The newsroom was empty, it was dark outside, and Laviana told it as a ghost tale, how the killer took his time strangling people, performing perversions. There is an old file in a drawer here, Laviana said. It has a copy of the first BTK message.

He waved a hand at the newsroom, which contained more than a hundred desks.

“If he ever does surface again, you’re going to see this entire room full of people head out the door with notebooks in their hands. Because that is what we’ll do to cover the story. It will be that big. Like the beginning of World War II.”

Paul Dotson, now a captain, took command of the Crimes Against Persons Bureau in 1996, which meant he became Landwehr’s supervisor. One of the first things he did was to issue a directive that other lieutenants in the bureau had to serve on a rotation, at staged intervals, to supervise homicide investigations. Landwehr would no longer be on call for all homicides twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

Landwehr hated it, but Dotson ignored his opposition. Every detective in the homicide unit had a habit of self-delusion, Dotson thought. They told themselves they could keep going on a case after forty-eight hours without sleep. They all had to have that kind of work ethic to do their jobs, but Dotson remembered how the unrelieved stress of investigating every homicide had nearly ruined his health when he did it. When Landwehr continued to gripe about it, Dotson brushed him off. “Come on, Kenny,” he said. “Look at how tired you look.” From now on, unless there was a huge case, Landwehr would get to take a break once in a while.

On the night of June 17, 1996, a one-story wooden home in the 1700 block of South Washington burned. Firefighters found a woman dead and her toddler daughter in critical condition.

The

Eagle

sent Laviana to the house the next day. He was surprised to see Landwehr and his detectives there. Was this a homicide?

Not long after the television reporters had finished their noon live shots, a big man in his twenties approached Laviana and said he was looking for the injured girl’s father. Laviana told him he was probably at the hospital with his daughter, then offered to drop the man there on his way back to the newsroom.

During the ride, Laviana tried to ask the man about the family. The man’s answers seemed odd and evasive. When they got to the hospital, Laviana handed him a business card and asked him to call. “What’s your name?” Laviana asked.

“Mike Marsh,” the man replied.

The little girl died six days after the fire. Meanwhile, Landwehr’s detectives had arrested Marsh. It became Wichita’s first death penalty case in decades.

Not long after Marsh’s arrest, Landwehr gave reporters a briefing about another homicide. Someone asked what detectives were doing to catch the killer.

“We’re going to see who Hurst drives to the hospital and arrest him,” Landwehr said.

One day Laviana heard a truck back up into the driveway of his home.

Laviana found Landwehr outside. Laviana was bewildered; the two men never socialized. Now the homicide chief had come to his home with a peculiar look on his face.

“Where do you want it?” Landwehr asked bluntly.

“Where do I want what?”

Landwehr waved a hand at what lay in the bed of the truck�a moldering, eight-foot-tall playhouse. It looked like a big piece of junk.

And now, with the help of Laviana’s wife, Landwehr unloaded the playhouse, heaved it over the chain-link fence, and dragged it to the middle of Laviana’s backyard. Landwehr avoided looking at him, but he was smiling. Laviana’s wife said Cindy Landwehr had told her that she had a playhouse she wanted to give away; Laviana’s wife thought that their three daughters would like it. Laviana just rolled his eyes. His daughters never entered the playhouse; they said it had cobwebs.

Capt. Al Stewart had never forgiven himself for failing to catch BTK. When he retired in 1985, he took copies of some of the old files with him to study. He had been through a lot on the job. When he was a young officer, a sniper’s bullet had knocked his police cap off his head. When he was a Ghostbuster, he had driven himself to tears and drink with frustration.

He spent his last years dying of emphysema. He warned his son Roger one day that he did not intend to suffer much longer. He was down to ten percent lung capacity; it took him half an hour to walk across the hall from his bedroom to the bathroom.

On March 31, 1998, Stewart, lying in bed, put a .25 caliber pistol to his head. He was only sixty-one.

On the nightstand beside his body, his family found one of his BTK files lying open. He had studied it until the end of his life.

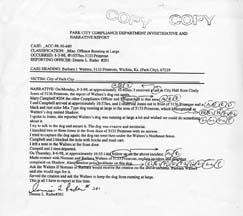

The phone call came to Patrick Walters’s law office around 11:00 AM on August 3, 1998. Someone who lived near the lawyer’s mother in Park City was on the phone. There was a guy in Barbara Walters’s backyard, the neighbor said, shooting at a dog with what looked like a tranquilizer rifle.

When Walters got to his mother’s house, he found Park City compliance officer Dennis Rader inside her fenced yard.

Patrick Walters asked him to get off the property. Rader would not leave. The Park City police chief happened to drive up then; he tried to calm both men. Then Walters noticed the dog was gone. A neighbor told him that Rader had opened the gate.

Three days later, Rader delivered a citation to Barbara Walters, saying she had allowed the dog, Shadow, to run loose.

She had received several tickets from Rader. He seemed obsessed, driving by slowly several times a day. She decided to fight the latest ticket. She was sure Rader intended to catch her dog and kill it.

One of Patrick Walters’s fellow attorneys, Danny Saville, agreed to represent Barbara Walters in Park City Municipal Court.

By the time of the hearing, Rader had supplied the judge with a half-inch-thick stack of papers supporting his case. He had audiotapes and videotapes of the dog. He had annotated, cross-referenced notes. The judge continued the case twice because Rader kept saying he needed time to prepare. All this over what would be a twenty-five-dollar ticket.

The judge found Barbara Walters guilty. She appealed, then settled before the case reached Sedgwick County District Court.

She got to keep Shadow but paid a fine.

She was glad to save the dog. Shadow had one characteristic Barbara Walters now cherished: he despised Rader.

On February 26, 1999, a man named Patrick Schoenhofer went out to buy Tylenol and was shot to death by a robber lurking near his apartment. Schoenhofer was only twenty-three.

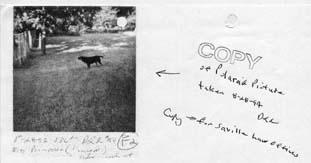

Park City compliance officer Dennis Rader took Polaroid photos of Shadow, a dog he claimed was a nuisance to the neighborhood and should be put down.

Roy Wenzl from the

Eagle

knocked on his widow’s door two days later. Erika Schoenhofer let him in and talked calmly about Patrick for a few minutes. But then a little boy came out of a nearby room. His name was Evan Alexander Schoenhofer, and he was two years old. He crawled up into his mother’s lap with a questioning look.

“Daddy?” he said.

Erika Schoenhofer hugged him.

“Daddy’s not here,” she said. She had turned her face away from her child as she hugged him, hiding tears.

Earlier that day Wenzl had talked to the cop assigned to the case, a detective with a crew cut named Kelly Otis. Otis was helpful and fun to talk with. He was also wary.

“Do not quote me,” he said. “I’ll talk enough to help you figure it out yourself, but keep me out of your story.”

Wenzl agreed. As he left to see the Shoenhofers, Otis looked hard at him.

“Treat those people right when you talk to them,” he said. He did not phrase it as a request.

That same week, Wenzl learned that a Wichita lawyer named Robert Beattie had recently spent forty-five minutes interviewing Charles Manson.

Rader’s annotated report for the Shadow court case, one of a half-inch-thick pile of documents he’d prepared.

Manson’s hippie clan had murdered a movie star and several other people in California in 1969; for decades afterward, Manson was the most notorious murderer in national history. Beattie gave Wenzl a transcript of the Manson interview. In spite of the killer’s fame, Beattie said, any reader of the transcript would see what a dull person Manson was. The media had made Manson the personification of evil, but in conversation he was boring.