Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door (23 page)

Read Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door Online

Authors: Roy Wenzl,Tim Potter,L. Kelly,Hurst Laviana

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Serial murderers, #Biography, #Social Science, #Murder, #Biography & Autobiography, #Serial Murders, #Serial Murder Investigation, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Case studies, #Serial Killers, #Serial Murders - Kansas - Wichita, #Serial Murder Investigation - Kansas - Wichita, #Kansas, #Wichita, #Rader; Dennis, #Serial Murderers - Kansas - Wichita

They said he was just doing his job.

More than once, Rader told her all her problems would go away if she got rid of her boyfriend.

In the fall of 2001, she came home to find a note from Rader: Her dog, a big Saint Bernard–chow mix, had gotten out of her yard. Rader had taken it to the pound.

When she went to get the dog, she was told she had to meet with Rader first. She went to see him but was told he wasn’t available. By the time they met the following Monday, the dog had been put down.

There were streaks of gray in Landwehr’s hair by the time the Carr brothers went to trial in the fall of 2002. Maybe it was his age (forty-seven); maybe it was stress. The burdens on his unit had been immense from the day of the soccer field murders, and the workload did not slacken in the year and a half it took to bring the defendants to trial on ninety-three criminal counts in a death penalty case. Landwehr’s cell phone rang day and night.

All the evidence held up. The trial was covered live on television, and the work done by the cops prompted praise.

To his friends, Landwehr seemed happier now: calm, resolved, and content.

Cindy Landwehr had done much to steady him, but his bond with his son seemed to deepen his maturity. After work, he would help James build forts out of sofa cushions and bedspreads in their basement. Within fifteen minutes, Landwehr would feel the weight of the world slide off, and he would read storybooks to his son and tuck him into bed and no longer dwell on work. His detectives were so experienced now that he did not have to deal hands-on with homicides. The detectives did most of the work, while Landwehr coordinated, gave advice, and ran administration.

He and Cindy were talking about building a new house; he was thinking about finishing that history degree he’d started working on twenty-nine years before.

Laviana had a little quirk that Wenzl liked to tease him about in the newsroom. Laviana would hear about a big event and say that it wasn’t really big enough to be a story. In 1998, for example, after the biggest grain elevator in the world blew up just south of Wichita, Wenzl had assigned Laviana as the lead reporter and teased him. “What do you think, Hurst? Is this a story or just a two-inch brief?”

But Laviana was a reporter of great skill. On May 4, 2003, the

Eagle

published a story by Laviana showing that more than two dozen people had been killed in the previous four years by prison parolees who should have been more closely supervised. Murder charges also were pending against parolees in eight other cases.

Reporting the story had taken years and a legal battle with the state that reached the Kansas Supreme Court. The story later won one of the biggest national awards the

Eagle

had earned in its 131-year history.

Laviana cared little for awards. He went back to writing cop stories.

A few weeks later, lawyer Robert Beattie started sending e-mails to Wenzl, telling him that he was teaching BTK as a class�and working on a BTK book. He suggested Wenzl write a story about this.

Wenzl turned to Laviana. “You’re the house expert on BTK,” he said. “Do you want this?”

Laviana made a face. “It’s a pretty old case,” he said.

Otis and Gouge had submitted Vicki Wegerle’s fingernail scraping and vaginal swab to the Sedgwick County Regional Forensic Science Center three years earlier, but the lab people had to give priority to new homicides. In August 2003, Otis and Gouge finally got the DNA results they’d been waiting for.

The DNA found under Vicki’s fingernail was different from the DNA found in the semen on the vaginal swab. To Otis, this was one more reminder that Bill Wegerle had told the truth in 1986. Otis had read in the interrogation transcript that Bill told detectives that they had no marital problems and that he had made love with Vicki the night before she died. Bill also told the cops he’d had a vasectomy shortly after his son was born.

Men who have a successful vasectomy ejaculate semen but no sperm. Gouge and Otis did not have Bill’s DNA to prove beyond doubt that the semen was Bill’s, but the lab tests showed it was semen with no sperm.

The finding prompted Otis and Gouge, with Landwehr’s blessing, to immediately request that the lab test samples of semen that BTK left at the Otero and Fox crime scenes. Those DNA profiles could then be compared with the DNA found under Vicki’s fingernail.

They still needed to get a mouth swab from Bill.

He had refused to cooperate three years earlier.

Now, Otis talked through options with Deputy District Attorney Kevin O’Connor. They decided that they could use a subpoena to compel Bill to give a DNA swab.

Otis wrote out a request for a subpoena. Once it was signed by a judge, it would be good for only seventy-two hours before it became void. Otis showed the subpoena request to O’Connor, who said it was written properly. But then Otis stuck the request in a desk drawer, unsigned by a judge. He would keep it, like a card to play down the road. For now, he could not bring himself to compel Bill Wegerle to do anything. Otis had read the interrogation transcripts from 1986 and knew how rough the cops had been on Bill. He thought the guy had suffered enough at the hands of the cops.

He would use the subpoena if he had to, but he wanted to talk Bill into giving a swab voluntarily.

Beattie sent more messages to Wenzl about his BTK book, and Wenzl kept putting Beattie off. But one day Wenzl went to Laviana: “Are you sure you don’t want this?”

Laviana said he wasn’t interested.

But Bill Hirschman in Florida was still obsessing about BTK, almost ten years after his departure from the

Eagle

. A few weeks later, Hirschman wrote Laviana a short e-mail.

Just six words.

“Do you know what Thursday is?” Hirschman wrote.

Laviana had to think for a moment:

Today was Monday, so…Thursday would be January 15.

Why does Hirschman care about January 15?

He typed an e-mail reply:

“It has to be Otero.”

Hirschman replied two days later. “So are you doing a thirtieth anniversary BTK piece?”

“I will now,” Laviana wrote.

He didn’t want to do it, though.

Hirschman liked anniversary stories. Laviana disliked them�they didn’t involve news.

Laviana took the idea to Tim Rogers, the

Eagle

’s assistant managing editor for local news. Laviana had to explain who BTK was; Rogers had worked at the paper less than three years.

“I’m not a big fan of anniversary stories,” Rogers said.

“I’m not either,” Laviana said.

“Let’s see if there’s anything new,” Rogers said. “If there is, we can do something.”

Laviana walked away, past Wenzl’s desk. No story, he thought.

Then he stopped.

“Roy,” he said. “Who was that guy who’s doing something with BTK?”

“Beattie,” Wenzl said. “A lawyer.”

“Do you have his number?”

Laviana’s story ran on Saturday, January 17:

It was a routine followed by thousands of Wichita women in the late 1970s:

- Upon arriving home, check the phone immediately.

- If the line is dead, get out.

“I don’t think people today realize the kind of tension there was in Wichita at that time,” said lawyer Robert Beattie….

Beattie said he wanted his book to document a chapter in Wichita history and prompt someone to come forward with information that would solve the case.

“I’m sure we will be contacted by both crackpots and well-meaning people who have little to contribute,” he said. “But I do not think we’ll be contacted by BTK.”

Hurst Laviana’s story in the

Eagle

about the thirtieth anniversary of the Otero killings. The article caused BTK to resurface.

In fact, BTK regarded the

Eagle

story and Beattie’s comments as a collective personal insult. He could hardly believe what he read:

Although the killings remain firmly implanted in the minds of those who lived through them, Beattie said many Wichitans probably have never heard of BTK.

He said he used the BTK case during a segment of his class last year and was surprised at the reaction.

“I had zero recognition from the students,” he said. “Not one of them had heard of it….

“I’m hoping someone will read the book and come forward with some information�a driver’s license, a watch, some car keys,” he said.

It had been thirteen years since BTK’s last murder. In that time Rader had confounded the experts, resisted the temptation to flaunt himself, and remained silent and safe. He had gotten away with murder ten times over.

But he found this story outrageous, and impossible to ignore.

Did they not remember him? Did they no longer feel the fear?

He would show them.

He went to his trophy stashes. He pulled out the three Polaroids he had snapped of Vicki Wegerle seventeen years before. He pulled out Vicki’s driver’s license.

Did the lawyer want a driver’s license?

Then he would have one.

Lt. Ken Landwehr was forty-nine years old and looked healthy again after the stress of the Carr brothers case had abated.

He had been a cop for twenty-five years; he had supervised the homicide detectives for nearly twelve, far longer than the three years that had nearly ruined the health of his predecessor. One night a week, he taught a class on serial killers at Wichita State University.

He had sad brown eyes, but laughed easily, unless he was pacing a homicide scene. He was going gray, but he hadn’t let himself go�a lot of women considered his creased face to be handsome. His face and hands were so brown that some people assumed he had Lebanese or Hispanic ancestors, but the tan was from playing golf. The rest of him was a blinding pale white.

He was still a sharp dresser: silver wire-frame glasses, dark brown or charcoal gray suits, white shirts he ironed himself, and dress shoes. A gold watch with a stretch band, a tiny silver cell phone attached to his left hip, his police badge attached to his right hip.

He was a pack-a-day smoker of Vantage cigarettes, but his son was nagging him to give up the habit.

Because of Cindy and James, he was content and happy.

That was about to change.

The letter arrived in the

Eagle

newsroom in an ordinary white envelope on March 19, 2004, a Friday. It was one of about seven hundred pieces of mail delivered to the paper every day.

It’s a wonder this one didn’t get tossed in the trash. Newsroom people throw obscurities away, and the sender of this message had made its contents obscure.

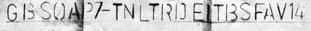

The first newsroom person to touch it was Glenda Elliott, the assistant to the editor. She sliced open the envelope and shook out a sheet of paper. She saw a grainy photocopy of three photos of a woman lying on a floor. And a driver’s license. Some strange stenciling at the top:

GBSOAP7-TNLTRDEITBSFAV14.

It looked like routine nut-job stuff.

Then, in the lower right corner, she noticed a faint, graffiti-like symbol, the letter B tipped over and made to look like breasts, the T and the K run together to make arms bound back and legs spread wide.