Black Mischief (5 page)

Authors: Evelyn Waugh

On

their heels came the hordes of Wanda and Sakuyu warriors. In the hills these

had followed in a diffuse rabble. Little units of six or a dozen trotted round

the stirrups of the headmen before them they drove geese and goats pillaged

from surrounding farms. Sometimes they squatted down to rest; sometimes they

ran to catch up. The big chiefs had bands of their own — mounted drummers

thumping great bowls of cowhide and wood, pipers blowing down six-foot chanters

of bamboo. Here and there a camel swayed above the heads of the mob. They were

armed with weapons of every kind: antiquated rifles, furnished with bandoliers

of brass cartridges and empty cartridge cases; short hunting spears, swords and

knives; the great, seven-foot broad-bladed spear of the Wanda; behind one

chief a slave carried a machine-gun under a velvet veil; a few had short bows

and iron-wood maces of immemorial design.

The

Sakuyu wore their hair in a dense fuzz; their chests and arms were embossed

with ornamental scars; the Wanda had their teeth filed into sharp points, their

hair braided into dozens of mud-caked pigtails. In accordance with their

unseemly usage, any who could wore strung round his neck the members of a slain

enemy.

As this

great host swept down on the city and surged through the gates, it broke into a

dozen divergent streams, spurting and trickling on all sides like water from a

rotten hose-pipe, forcing out jets of men, mounts and livestock into the

by-ways and back streets, eddying down the blind alleys and into enclosed

courts. Solitary musicians, separated from their bands, drum med and piped

among the straggling crowds; groups split away from the mêlée and began dancing

in the alleys; the doors of the liquor shops were broken in and a new and

nastier element appeared in the carnival, as drink-crazed warriors began to re-enact

their deeds of heroism, bloodily laying about their former comrades-in-arms

with knives and clubs.

‘God,’

said Connolly, ‘I shall be glad when I’ve got this menagerie off my hands. I

wonder if his nibs has really bolted. Anything is possible in this abandoned

country.’

No one

appeared in the streets. Only rows of furtive eyes behind the shuttered windows

watched the victors slow progress through the city. In the main square the

General halted the guards and such of the irregular troops as were still

amenable to discipline; they squatted on the ground, chewing at bits of sugar

cane, crunching nuts and polishing their teeth with little lengths of stick,

while above the drone of confused revelling which rose from the side streets,

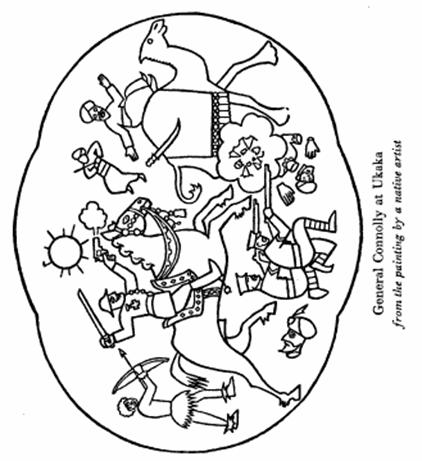

Connolly from the saddle of his mule in classical form exhorted his legions.

‘Guards,’

he said loudly, ‘Chiefs and tribesmen of the Azanian Empire. Hear me. You are

good men. You have fought valiantly for your Emperor. The slaughter was very

splendid. It is a thing for which your children and your children’s children

will hold you in honour. It was said in the camp that the Emperor had gone over

the sea. I do not know if that is true. If he has, it is to prepare a reward

for you in the great lands. But it is sufficient reward to a soldier to have

slain his enemy.

‘Guards,

Chiefs and tribesmen of the Azanian Empire. The war is over. It is fitting that

you should rest and rejoice. Two things only I charge you are forbidden. The

white men, their houses, cattle, goods or women you must not take. Nor must you

burn anything or any of the houses nor pour out the petrol in the streets. If

any man do this he shall be killed. I have spoken. Long live the Emperor.

‘Go on,

you lucky bastards,’ he added in English. ‘Go .and make whoopee. I must get a

brush up and some food before I do anything else.’

He rode

across to the Grand Azanian Hotel. It was shut and barred. His two servants

forced the door and he went in. At the best of times, even when the fortnightly

Messageries liner was in and gay European sightseers paraded every corner of

the city, the Grand Azanian Hotel had a gloomy and unwelcoming air. On this

morning a chill of utter desolation struck through General Connolly as he

passed through its empty and darkened rooms. Every movable object had been

stripped from walls and floor and stowed away subterraneously during the

preceding night. But the single bath at least was a fixture. Connolly set his

servants to work pumping water and unpacking his uniform cases. Eventually an

hour later he emerged, profoundly low in spirits, but clean, shaved and very

fairly dressed. Then he rode towards the fort where the Emperor’s colours hung

limp in the sultry air. No sign of life came from the houses; no welcome; no

resistance. Marauding bands of his own people skulked from corner to corner;

once a terrified Indian rocketed up from the .gutter and shot across his path

like a rabbit. It was not until he reached the White Fathers’ mission that he

heard news of the Emperor. Here he encountered a vast Canadian priest with

white habit and sun-hat and spreading crimson beard, who was at that moment

occupied in shaking almost to death the brigade sergeant-major of the Imperial

Guard. At the General’s approach the reverend father released his victim with

one hand —keeping a firm grip in his woollen hair with the other — removed the

cheroot from his mouth and waved it cordially.

‘Hullo,

General, back from the wars, eh? They’ve been very anxious about you in the

city. Is this creature part of the victorious army?’

‘Looks

like one of my chaps. What’s he been up to?’

‘Up to?

I came in from Mass and found him eating my breakfast.’ A tremendous buffet on

the side of his head sent the sergeant-major dizzily across the road. ‘Don’t

you let me find any more of your fellows hanging round the mission today or

there’ll be trouble. It’s always the same when you have troops in a town. I

remember in Duke Japheth’s rebellion, the wretched creatures were all over the

place. They frightened the sisters terribly over at the fever hospital.’

‘Father,

is it true that the Emperor’s cut and rur?’

‘If he

hasn’t he’s about the only person. I had that old fraud of an Armenian

Archbishop in here the other night, trying to make me join him in a motor-boat.

I told him I’d sooner have my throat cut on dry land than face that crossing in

an open boat. I’ll bet he was sick.’

‘But

you don’t know where the Emperor is?’

‘He

might be over in the fort. He was the other day. Silly young ass, pasting up

proclamations all over the town. I’ve got other things to bother about than

young Seth. And mind you keep your miserable savages from my mission or they’ll

know the reason why. I’ve got a lot of our people camped in here so as to be

out of harm’s way, and I am not going to have them disturbed. Good morning to

you, General.’

General

Connolly rode on. At the fort he found no sentry on guard. The courtyard was

empty save for the body of Ali, which hay on its face in the dust, the cord

which had strangled him still tightly twined round his neck. Connolly turned it

over with his boot but failed to recognize the swollen and darkened face.

‘So His

Imperial Majesty

has

shot the moon.’

He

looked into the deserted guard-house and the lower rooms of the fort; then he

climbed the spiral stone staircase which led to Seth’s room, and here, lying

across the camp bed in spotted silk pyjamas recently purchased in the Place Vendôme,

utterly exhausted by the horror and insecurity of the preceding night, lay the

Emperor of Azania fast asleep.

From

his bed Seth would only hear the first, rudimentary statement of his victory.

Then he dismissed his commander-in-chief and with remarkable self-restraint

insisted on performing a complete and fairly elaborate toilet before giving

his mind to the details of the situation. When, eventually, he came downstairs

dressed in the full and untarnished uniform of the Imperial Horse Guards, he

was in a state of some elation. ‘You see, Connolly,’ he cried, clasping his

general’s hand with warm emotion, ‘I was right. I knew that it was impossible for

us to fail.’

‘We

came damn near it once or twice,’ said Connolly.

‘Nonsense,

my dear fellow. We are Progress and the New Age. Nothing can stand in our way.

Don’t

you see?

The world is already ours; it is our world now, because we are of

the Present. Seyid and his ramshackle band of brigands were the Past. Dark

barbarism. A cobweb in a garret; dead wood; a whisper echoing in a sunless

cave. We are Light and Speed and Strength, Steel and Steam, Youth, Today and

Tomorrow. Don’t you see? Our little war was won on other fields five centuries

back.’ The young darky stood there transfigured; his eyes shining; his head

thrown back; tipsy with words. The white man knocked out his pipe on the heel

of his riding boot and felt for a pouch in his tunic pocket.

‘All right,

Seth, say it your way. All I know is that

my

little war was won the day

before yesterday and by two very ancient weapons — lies and the long spear.’

‘But my

tank? Was it not that which gave us the victory?’

‘Marx’s

tin can? A fat lot of use that was. I told you you were wasting money, but you

would have the thing. The best thing you can do is to present it to Debra Dowa

as a war memorial, only you couldn’t get it so far. My dear boy, you can’t take

a machine like that over this country under this sun. The whole thing was red

hot after five miles. The two poor devils of Greeks who had to drive it nearly

went off their heads. It came in handy in the end though. We used it as a

punishment cell. It was the one thing these black bastards would really take notice

of. It’s all right getting on a high horse about progress now that everything’s

over. It doesn’t hurt anyone. But if you want to know, you were as near as

nothing to losing the whole bag of tricks at the end of last week. Do you know

what that clever devil Seyid had done? Got hold of a photograph of you taken at

Oxford in cap and gown. He had several thousand printed and circulated among

the guards. Told them you’d deserted the Church in England and that there you

were in the robes of an English Mohammedan. All the mission boys fell for it.

It was no good telling them. They were going over to the enemy in hundreds

every night. I was all in. There didn’t seem a damned thing to do. Then I got

an idea. You know what the name of Amurath means among the tribesmen. Well, I

called a shari of all the Wanda and Sakuya chiefs and spun them the yarn. Told

them that Amurath never died — which they believed already most of them — but

that he had crossed the sea to commune with the spirits of his ancestors; that

you were Amurath, himself, come back in another form. It went down from the

word go. I wish you could have seen their faces. The moment they’d heard the

news they were mad to be at Seyid there and then. It was all I could do to keep

them back until I had him where I wanted him. What’s more, the story got

through to the other side and in two days we had a couple of thousand of

Seyid’s boys coming over to us. Double what we’d lost on the Mohammedan story

and real fighters — not dressed-up mission boys. Well, I kept them back as best

I could for three days. We were on the crest of the hills al the time and Seyid

was down in the valley, kicking up the devil burning villages, trying to make

us come down to him. He was getting worried about the desertions. Well, on the

third day I sent half a company of guards down with a band and a whole lot of

mules and told them to make themselves as conspicuous as they could straight

in front of him in the Ukaka pass. Trust the guards to do that. He did just

what I expected; thought it was the whole army and spread out on both sides

trying to surround them. Then I let the tribesmen in on his rear. My word, I’ve

never seen such a massacre. Didn’t they enjoy themselves, bless them. Half of

them haven’t come back yet; they’re still chasing the poor devils all over the

hills.’

‘And

the usurper Seyid, did he surrender?’

‘Yes,

he surrendered all right. But, look here, Seth, I hope you aren’t going to mind

about this, but you see how it was, well, you see, Seyid surrendered and …’

‘You

don’t mean you’ve let him escape?’

‘Oh no,

nothing like that, but the fact is, he surrendered to a party of Wanda … and,

well, you know what the Wanda are.’

‘You

mean …..

‘Yes,

I’m afraid so. I wouldn’t have had it happen for anything. I didn’t hear about

it until afterwards.’

‘They

should not have eaten him — after all, he was my father … It is so … so

barbarous.’

‘I knew

you’d feel that way about it, Seth, and I’m sorry. I gave the headmen twelve

hours in the tank for it.’