Blind to Betrayal: Why We Fool Ourselves We Aren't Being Fooled (25 page)

Read Blind to Betrayal: Why We Fool Ourselves We Aren't Being Fooled Online

Authors: Jennifer Freyd,Pamela Birrell

It is a common phenomenon for people to become angry with their parents during the course of psychotherapy. It is also a common phenomenon for these same people to enter into a mature and conscious relationship with their parents later in therapy—at least, when those parents do not continue to attack their children's vulnerability. I know of cases where incest has occurred and yet reunion has been possible because of the parents' willingness to confront their own behavior and to remain in relationships without intrusion. This would be even more likely to happen in families where “false memories” have been “implanted.”

The problem of abuse in our society is a complex one. It involves power, control, victimization, denial, and, most of all, pain. Peter Vaill has movingly described the pain in our organizations and in our culture: “We can't just share our pain and confusion with each other. . . . There is massive suppression of anguish going on in the organizations and communities of the developed world—no one's fault in particular; just a fundamental part of our culture. I think there is a lot of collective, but unexpressed, anguish in our modern organizations.”

6.

We, as a society, must find ways to experience and share this pain. There are no simple solutions. Some therapists have attempted to foreclose on the pain by attaching it to discrete memories. The FMSF has attempted to cover the pain by attacking the messenger. We need to somehow be able to go through the pain to find the meaning it holds for each of us.

I would ask that each of you consider carefully your particular motives for being associated with this organization and to decide whether your objectives are being met. Jennifer Freyd has been deeply hurt by this organization, as have many other survivors. Those dealing with real memories of incest are in turmoil, in pain, and in constant doubt of their own reality. They feel shameful, anxious, and frightened. It is often easier for them to believe that they are crazy than to face the truth of their past. This organization has done them a great disservice. It is particularly tragic because the needs of a small number of those [who are] truly falsely accused could have been met without causing such damage.

7.

Only two members of the board ever responded to the letter, and their responses were terse and uncompromising, basically stating that they did not see this side of the controversy at all and were not willing to engage in dialogue.

This is how it all began. Perhaps the clarity of this betrayal was its saving grace for us. We could no longer be blind. Speaking out was wrenching for both of us. We spoke out at a time when the powers of society and our profession were clearly aligned on the side of blindness and oppression of survivors. We feared and received reprisal, which included being disinvited to speaking engagements and getting threatening letters. We were even picketed outside the psychology building. It was a harrowing time, and we were tempted to retreat into our academic havens. We are truly glad we didn't. Only when blindness is gone can healing truly begin.

Betrayal can separate us from others, but betrayals when confronted can bring us together. This is what happened to us. Twenty years after encountering and then confronting the Jane Doe article, we continue to learn and discover together.

Notes

1.

J. J. Freyd, “Theoretical and Personal Perspectives on the Delayed Memory Debate,” in

Proceedings of the Center for Mental Health at Foote Hospital's Continuing Education Conference, Controversies around Recovered Memories of Incest and Ritualistic Abuse

(Ann Arbor, MI: Foote Hospital, 1993), 69–108.

2.

G. Ganaway, “Town Meeting: Delayed Memory Controversy in Abuse Recovery,” Panel presented at the Fifth Anniversary Eastern Regional Conference on Abuse and Multiple Personality, June 1993, Alexandria, VA (1993a); G. Ganaway, Panel presented at The Center for Mental Health at Foote Hospital's Continuing Education Conference: “Controversies around Recovered Memories of Incest and Ritualistic Abuse,” August 1993, Ann Arbor, MI (1993b).

3.

M. Gardner, “Notes of a Fringe Watcher: The False Memory Syndrome,”

Skeptical Inquirer 17

(3) (1993): 370–375.

4.

J. Herman,

Trauma and Recovery

(New York: Basic Books, 1992); J. Herman and E. Schatzow, “Recovery and Verification of Memories of Childhood Trauma.”

Psychoanalytic Psychology 4

(1987): 1–16.

5.

R. Ofshe and E. Watters, “Making Monsters,”

Society

(1993): 4–16.

6.

P. B. Vaill, “The Rediscovery of Anguish,”

Creative Change 10

(3) (1990): 18–24.

7.

P. Birrell, “An Open Letter to the Advisory Board Members of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation,”

Moving Forward Newsjournal 2

(5) (1993): 4–5.

14

Now I See: Facing Betrayal Blindness

Throughout this book, we have laid out the many ways that betrayal and betrayal blindness can separate us from one another, can silence us, and can create an atmosphere of distrust and hopelessness. It is only in facing betrayal and the pain of it that we can grow into ourselves and claim our own truth. All of the people who were brave enough to tell us their stories have both demonstrated the toxicity of betrayal and its blindness and also planted seeds of hope. They all have gone from isolation and despair to hope and at least the promise of intimacy in their lives. They are more comfortable in their own skins, and they are able to love and trust themselves and others more wholeheartedly. They have demonstrated the healing power of loving relationships and the importance of showing that love to each other. There is no single way of accomplishing this healing. Their stories, however, as well as the research we have described, point to some general guidelines to prevent and recover from betrayal and its blindness.

You picked up this book for a reason. Perhaps you are reading this book simply because you find the topic fascinating. Perhaps you work for an institution that has the power to betray, and you would like to create an environment where betrayal is addressed and blindness is confronted. Perhaps you know someone struggling with betrayal and its devastating effects. Perhaps you are grappling with a dawning awareness of betrayal and betrayal blindness in your own life.

If you are touched by betrayal in any of these ways, you may be wondering what you can do to confront, heal from, and prevent betrayal and its blindness. As we conclude this book, we'd like to offer some suggestions for awareness and healing. These suggestions are for people who have been betrayed, their friends and supporters, as well as those institutions and individuals who hold the power either to betray or to create a safer world. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but rather a starting place.

For Those Who Suspect They Have Been Betrayed

If you suspect or know that you have been betrayed, first of all take care of yourself. Betrayal is pernicious, especially if you have been blind to it. Although that blindness helped you survive by protecting important relationships, you have likely paid a high price in harm to your well-being. If you have been blind to betrayal, you have likely developed habits of perception, habits of thought, and patterns of behavior that are geared more to the maintenance of necessary relationships than to freedom, intimacy, and healing. As a consequence, you may have trouble believing in yourself or forming safe and loving relationships. In general, you may not have developed habits that show self-caring and self-nurturing. Change might even seem impossible to you. Yet change is possible. Here are some places to start. Some of these are obvious, but others are less so.

The Role of the Body

In chapter 9, we describe research showing that exposure to traumatic betrayal has many toxic effects. This includes basic physical health. People who have been extensively betrayed tend not to be as physically healthy as those who have not had such a history. It is difficult to do the relational and emotional work of healing without first addressing your basic physical health.

First, it is important to have adequate sleep hygiene. You need to get sufficiently restful and uninterrupted sleep in order to heal the mind. Try to go to bed only you are when sleepy and wake up around the same time every day. Adhere to bedtime routines that will give your body cues that it is time to slow down and sleep. For example, you might try listening to relaxing music, reading something soothing, having a cup of caffeine-free tea, or doing relaxation exercises.

Second, you need to get sufficient exercise. Do what you like to do, as long as you are moving your body. Ride your bike, swim, dance, walk, do yoga, or do whatever physical activity brings you pleasure. It is hard to overestimate the benefits of exercise on your sense of well-being.

Third, make an effort to eat well and to eat foods that make your body thrive. This means eating a variety of whole foods. Most people find that they feel more energetic and healthy if they avoid excessive amounts of foods that are high in salt, saturated and trans fats, cholesterol, and added sugar. You may discover that eating a sufficient amount of protein (such as fish, beans, raw nuts, and seeds) and a large variety of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains gives your body a feeling of fullness and health.

If these measures—sleeping well, exercising, and adhering to a healthy diet—fail to bring a sense of good health, it is essential that you see a doctor to assess whether there are underlying conditions.

If you do attend to basic physical self-care, your body can be a powerful ally. Although we rarely think of our bodies as important in dealing with a psychological problem such as betrayal, in fact the body can be crucial in promoting our awareness and healing. A friend and colleague put it this way: “My biggest protection now against betrayal blindness is being more fully in my body and paying careful attention to what it is telling me. When I had my worst experiences of betrayal, I was numb and dissociated from my body. I've taken up a martial art, which has fast-tracked my awareness of what danger and threat feel like, because I need to notice them in training in order to be able to respond and not be blind to the realities of attack (even though it's a training attack, it's still a place in which I can get physically hurt!). I now know what I feel when my body's cheater detectors come online, and I've learned to stop and pay careful and close attention to those physical sensations.”

Being in touch with our bodies is indispensable for overall health, overall healing, and becoming aware of betrayals.

The Role of Relationships

As important as a healthy body is for healing, equally important are healthy relationships. In simple terms, it is a good idea to stay away from people who feel toxic to you, spend time with people who feel safe to you, and seek out relationships in which you feel good about yourself.

Psychologist Belle Liang and her colleagues developed the “Relational Health Indices Scale.”

1.

We have found that the items from this scale provide useful information to assess the health of current relationships. Ask yourself some of the following questions (based on the Relational Health Index) about a friend:

1.

Even when I have difficult things to share, I can be honest and real with my friend.2.

After a conversation with my friend, I feel uplifted.3.

The more time I spend with my friend, the closer I feel to him/her.4.

I feel understood by my friend.5.

It is important to us to make our friendship grow.6.

I can talk to my friend about our disagreements without feeling judged.7.

My friendship inspires me to seek other friendships like this one.8.

I am comfortable sharing my deepest feelings and thoughts with my friend.9.

I have a greater sense of self-worth through my relationship with my friend.10.

I feel positively changed by my friend.11.

I can tell my friend when he/she has hurt my feelings.12.

My friendship causes me to grow in important ways.

If you answered yes to all or most of these questions, then you are likely in a healthy relationship with your friend. However, if you answered no to many of them, the relationship may not be one in which you can grow and heal. Perhaps you can change this relationship. You might find that if you model the behaviors you want from your friend, some positive changes will naturally occur. If you cannot repair your current friendships, find friends or perhaps a therapist to create a relationship in which you can answer these questions affirmatively.

Another way of thinking about this was suggested to us by our friend and colleague. Here is what she said: “I've also learned to notice when I'm having a long argument with someone else in my head. That's a data point that I am being unseen and unheard and could be at risk of being betrayed. If I'm in those conversations with someone, I know that I need to pay attention to how I'm silencing myself in the relationship and move toward unsilencing.”

Do you ever feel silenced in this way in your current relationships? Perhaps it is time to either speak up or seek a relationship in which you don't feel silenced.

Yet another way of thinking about this is in terms of the dependence you may have in certain relationships. Relationships that you feel you “cannot live without” and those in which you feel psychologically, financially, or physically dependent on someone else are potentially relationships in which blindness develops. Dependency in relationships is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, we are all dependent on others. Interdependence is healthy. However, sometimes extreme dependency can be toxic, increasing the probability of betrayal and betrayal blindness. You might ask yourself if you are comfortable with your level of dependency on a particular relationship. If not, is it possible for you to become less dependent? Either way, it is wise to be aware that dependency can potentially make you prone to betrayal blindness.

The Role of Disclosure

In chapter 11, we discuss the healing that comes from knowing and telling about betrayal. We also discuss the importance of disclosing only when it is safe. Ideally, you can find someone who will listen to you nonjudgmentally and will support you as tell your story. Research we discuss in chapter 10 also suggests that you might get benefits from telling your story in a private way, perhaps by writing in a journal. Words, whether spoken or written, can be a powerful way to communicate a betrayal story, but they are not the only way. Music, art, and dance can be used to express a betrayal experience.

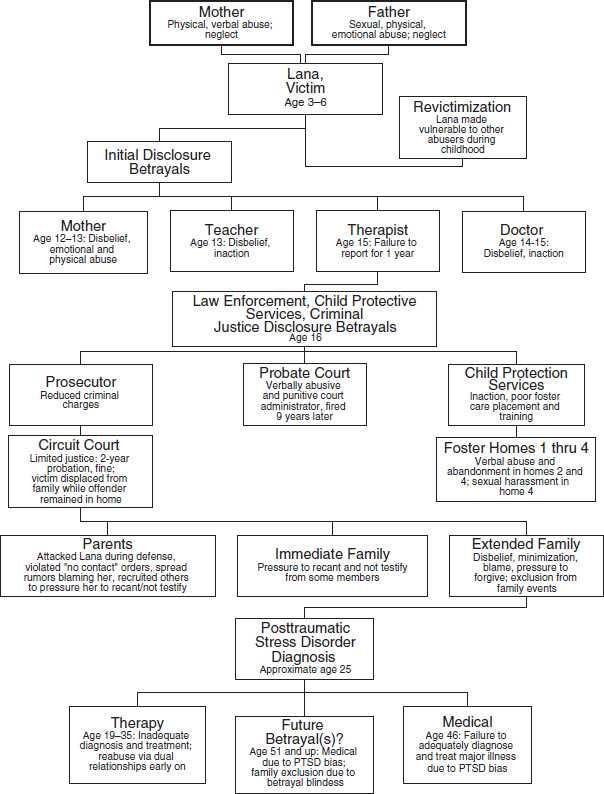

Some people have been particularly creative in figuring out ways to disclose and tell their stories. Lana R. Lawrence, an accomplished photographer, found it helpful to work through her history of betrayal using flow charts. Flow charts are both visual and well-suited for recording facts. Lana experienced a number of severe childhood betrayals at the hands of caregivers, as well as subsequent and intersecting betrayals when she tried to get help for the initial injuries.

She was able to capture the sequence of events, their complex interactions, and the scope of the betrayals by creating flow charts. “I think that flow charts are a really good way of visualizing the initial trauma and then the subsequent traumas that might follow. I've done it for each parent and began with each disclosure in my teens and then through the court system, the family losses/betrayals, religion, the educational system, mental health system and medical system betrayals, and so on. I am sure there will be categories in the future, as I wonder if betrayals related to the initial trauma can span a lifetime.”

In disclosing your story to another person, the way that he or she listens is crucial. Later in this chapter, we discuss ways that friends and other supportive people can be good listeners. Knowing what good listening consists of should help you select others to whom you can safely tell your story. Remember that you can be harmed by someone who does not listen to you respectfully and nonjudgmentally.

Understanding the Process

Even with all of this in place—a healthy body, supportive relationships, and safe disclosure—healing from betrayal and its blindness is challenging. It is not a simple process of telling and then knowing. Jennifer M. Gómez and Laura Noll, doctoral students in clinical psychology, recently captured some of this complexity and offered the following advice for someone newly confronting betrayal blindness.