Blockade Billy (2 page)

Authors: Stephen King

Tags: #King; Stephen - Prose & Criticism, #Horror, #General, #Fiction - General, #Suspense, #Horror - General, #Fiction, #Sports

“All new gear,” says he. “Except for the glove. I have to have Billy’s old glove, you know. Billy Junior and me’s been the miles.”

“Well, that’s fine with me.” And we went on in to what the sports writers used to call Old Swampy in those days.

I hesitated over giving him 19, because it was poor old Faraday’s number, but the uniform fit him without looking like pajamas, so I did. While he was dressing, I said: “Ain’t you tired? You must have driven almost nonstop. Didn’t they send you some cash to take a plane?”

“I ain’t tired,” he said. “They might have sent me some cash to take a plane, but I didn’t see it. Could we go look at the field?”

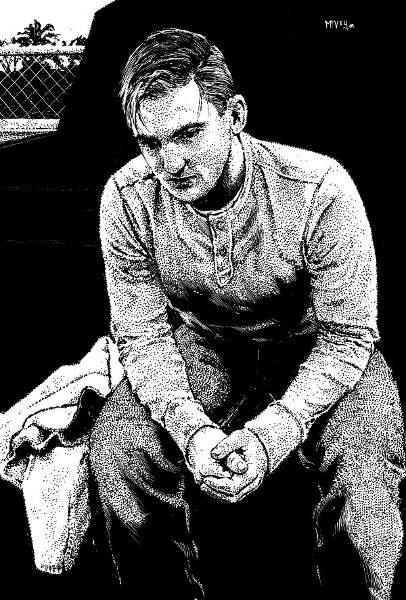

I said we could, and led him down the runway and up through the dugout. He walked down to home plate outside the foul line in Faraday’s uniform, the blue 19 gleaming in the morning sun (it wasn’t but eight o’clock, the groundskeepers just starting what would be a long day’s work).

I wish I could tell you how it felt to see him taking that walk, Mr. King, but words are your thing, not mine. All I know is that back-to he looked more like Faraday than ever. He was ten years younger, of course…but age doesn’t show much from the back, except sometimes in a man’s walk. Plus he was slim like Faraday, and slim’s the way you want your shortstop and second baseman to look, not your catcher. Catchers should be built like fireplugs, the way Johnny Goodkind was. This one looked like a bunch of broken ribs waiting to happen.

He had a firmer build than Frank Faraday, though; broader butt and thicker thighs. He was skinny from the waist up, but looking at him ass-end-going-away, I remember thinking he looked like what he probably was: an Iowa plowboy on vacation in scenic Newark.

He went to the plate and turned around to look out to dead center. He had dark hair and a lock of it had fallen on his forehead. He brushed it away and just stood there taking it all in—the silent, empty stands where over fifty thousand people would be sitting that afternoon, the bunting already hung on the railings and fluttering in the little morning breeze, the foul poles painted fresh Jersey Blue, the groundskeepers just starting to water. It was an awesome sight, I always thought, and I could imagine what was going through the kid’s mind, him that had probably been home milking the cows just a week ago and waiting for the Cornholers to start playing in mid-May.

I thought,

Poor kid’s finally getting the picture. When he looks over here, I’ll see the panic in his eyes. I may have to tie him down in the locker room to keep him from jumping in that old truck of his and hightailing it back to God’s country

.

But when he looked at me, there was no panic in his eyes. No fear. Not even nervousness, which I would have said every player feels on Opening Day. No, he looked perfectly cool standing there behind the plate in his Levi’s and light poplin jacket.

“Yuh,” he says, like a man confirming something he was pretty sure of in the first place. “Billy can hit here.”

“Good for him,” I tells him. It’s all I can think of to say.

“Good,” he says back. Then—I swear—he says, “Do you think those guys need help with them hoses?”

I laughed. There was something strange about him, something off, something that made folks nervous…but that something made people take to him, too. Kinda sweet. Something that made you want to like him in spite of feeling he wasn’t exactly right in the top story. Joe felt it right away. Some of the players did, too, but that didn’t stop them from liking him. I don’t know, it was like when you talked to him what came back was the sound of your own voice. Like an echo in a cave.

“Billy,” I said, “groundskeeping ain’t your job. Bill’s job is to put on the gear and catch Danny Dusen this afternoon.”

“Danny Doo,” he said.

“That’s right. Twenty and six last year, should have won the Cy Young, didn’t. He’s still got a red ass over that. And remember this: if he shakes you off, don’t you dare flash the same sign again. Not unless you want your pecker and asshole to change places after the game, that is. Danny Doo is four games from two hundred wins, and he’s going to be mean as hell until he gets there.”

“Until he gets there.” Nodding his head.

“That’s right.”

“If he shakes me off, flash something different.”

“Yes.”

“Does he have a changeup?”

“Do you have two legs? The Doo’s won a hundred and ninety-six games. You don’t do that without a changeup.”

“Not without a changeup,” he says. “Okay.”

“And don’t get hurt out there. Until the front office can make a deal, you’re what we got.”

“I’m it,” he says. “Gotcha.”

“I hope so.”

Other players were coming in by then, and I had about a thousand things to do. Later on I saw the kid in Jersey Joe’s office, signing whatever needed to be signed with Kerwin McCaslin hanging over him like a vulture over roadkill, pointing out all the right places. Poor kid, probably six hours’ worth of sleep in the last sixty, and he was in there signing five years of his life away. Later I saw him with Dusen, going over the Boston lineup. The Doo was doing all the talking, and the kid was doing all the listening. Didn’t even ask a question, so far as I saw, which was good. If the kid had opened his head, Danny probably would have bit it off.

About an hour before the game, I went in to Joe’s office to look at the lineup card. He had the kid batting eighth, which was no shock. Over our heads the murmuring had started and you could hear the rumble of feet on the boards. Opening Day crowds always pile in early. Listening to it started the butterflies in my gut, like always, and I could see Jersey Joe felt the same. His ashtray was already overflowing.

“He’s not big like I hoped he’d be,” he said, tapping Blakely’s name on the lineup card. “God help us if he gets cleaned out.”

“McCaslin hasn’t found anyone else?”

“Maybe. He talked to Hubie Rattner’s wife, but Hubie’s on a fishing trip somewhere in Rectal Temperature, Michigan. Out of touch until next week.”

“Cap—Hubie Rattner’s forty-three if he’s a day.”

“Beggars can’t be choosers. And be straight with me—how long do you think that kid’s gonna last in the bigs?”

“Oh, he’s probably just a cup of coffee,” I says, “but he’s got something Faraday didn’t.”

“And what might that be?”

“Dunno. But if you’d seen him standing behind the plate and looking out into center, you might feel better about him. It was like he was thinking ‘This ain’t the big deal I thought it would be.’”

“He’ll find out how big a deal it is the first time Ike Delock throws one at his nose,” Joe said, and lit a cigarette. He took a drag and started hacking. “I got to quit these Luckies. Not a cough in a carload, my ass. I’ll bet you twenty goddam bucks that kid lets Danny Doo’s first curve go right through his wickets. Then Danny’ll be all upset—you know how he gets when someone fucks up his train ride—and Boston’ll be off to the races.”

“Ain’t you just the cheeriest Cheerio,” I says.

He stuck out his hand. “Bet.”

And because I knew he was trying to take the curse off it, I shook his hand. That was twenty I won, because the legend of Blockade Billy started that very day.

You couldn’t say he called a good game, because he didn’t call it. The Doo did that. But the first pitch—to Frank Malzone—

was

a curve, and the kid caught it just fine. Not only that, though. It was a cunt’s hair outside and I never saw a catcher pull one back so fast, not even Yogi. Ump called strike one and it was us off to the races, at least until Williams hit a solo shot in the fifth. We got that back in the sixth, when Ben Vincent put one out. Then in the seventh, we’ve got a runner on second—I think it was Barbarino—with two outs and the new kid at the plate. It was his third at bat. First time he struck out looking, the second time swinging. Delock fooled him bad that time, made him look silly, and he heard the only boos he ever got while he was wearing a Titans uniform.

He steps in, and I looked over at Joe. Seen him sitting way down by the lineup card, just looking at the floor and shaking his head. Even if the kid worked a walk, The Doo was up next, and The Doo couldn’t hit a slowpitch softball with a tennis racket. As a hitter that guy was fucking terrible.

I won’t drag out the suspense; this ain’t no kids’ sports novel. Although whoever said life sometimes imitates art was right, and it did that day. Count went to three and two. Then Delock threw the sinker that fooled the kid so bad the first time and damn if the kid didn’t suck for it again. Except Ike Delock turned out to be the sucker that time. Kid golfed it right off his shoetops the way Ellie Howard used to do and shot it into the gap. I waved the runner in and we had the lead back, two to one.

Everybody in the joint was on their feet, screaming their throats out, but the kid didn’t even seem to hear it. Just stood there on second, dusting off the seat of his pants. He didn’t stay there long, because The Doo went down on three pitches, then threw his bat like he always did when he got struck out.

So maybe it’s a sports novel after all, like the kind you probably read in junior high school study hall. Top of the ninth and The Doo’s looking at the top of the lineup. Strikes out Malzone, and a quarter of the crowd’s on their feet. Strikes out Klaus, and half the crowd’s on their feet. Then comes Williams—old Teddy Ballgame. The Doo gets him on the hip, oh and two, then weakens and walks him. The kid starts out to the mound and Doo waves him back—just squat and do your job, sonny. So sonny does. What else is he gonna do? The guy on the mound is one of the best pitchers in baseball and the guy behind the plate was maybe playing a little pickup ball behind the barn that spring to keep in shape after the day’s cowtits was all pulled.

First pitch, goddam! Williams takes off for second. The ball was in the dirt, hard to handle, but the kid still made one fuck of a good throw. Almost got Teddy, but as you know, almost only counts in horseshoes. Now everybody’s on their feet, screaming. The Doo does some shouting at the kid—like it was the kid’s fault instead of just a bullshit pitch—and while Doo’s telling the kid he’s a lousy choker, Williams calls time. Hurt his knee a little sliding into the bag, which shouldn’t have surprised anyone; he could hit like nobody’s business, but he was a leadfoot on the bases. Why he stole a bag that day is anybody’s guess. It sure wasn’t no hit-and-run, not with two outs and the game on the line.

So Billy Anderson comes in to run for Teddy…who probably would have been royally roasted by the manager if he’d been anyone but Teddy. And Dick Gernert steps in, .425 slugging percentage or something like it. The crowd’s going apeshit, the flag’s blowing out, the frank wrappers are swirling around, women are goddam crying, men are yelling for Jersey Joe to yank The Doo and put in Stew Rankin—he was what people would call the closer today, although back then he was just known as a short-relief specialist.

But Joe crossed his fingers and stuck with Dusen.

The count goes three and two, right? Anderson off with the pitch, right? Because he can run like the wind and the guy behind the plate’s a first-game rook. Gernert, that mighty man, gets just under a curve and beeps it—not bloops it but

beeps

it—behind the pitcher’s mound, just out of The Doo’s reach. He’s on it like a cat, though. Anderson’s around third and The Doo throws home from his knees. That thing was a fucking

bullet

.

I know what you’re thinking

I’m

thinking, Mr. King, but you’re dead wrong. It never crossed my mind that our new rookie catcher was going to get busted up like Faraday and have a nice one-game career in the bigs. For one thing, Billy Anderson was no moose like Big Klew; more of a ballet dancer. For another…well…the kid was

better

than Faraday. I think I knew that the first time I saw him, sitting on the bumper of his beshitted old truck with his wore-out gear stored in the back.

Dusen’s throw was low but on the money. The kid took it between his legs, then pivoted around, and I seen he was holding out

just the mitt

. I just had time to think of what a rookie mistake that was, how he forgot that old saying

two hands for beginners

, how Anderson was going to knock the ball loose and we’d have to try to win the game in the bottom of the ninth. But then the kid lowered his left shoulder like a football lineman. I never paid attention to his free hand, because I was staring at that outstretched catcher’s mitt, just like everyone else in Old Swampy that day. So I didn’t exactly see what happened, and neither did anybody else.

What I

saw

was this: the kid whapped the glove on Anderson’s chest while he was still three full steps from the dish. Then Anderson hit the kid’s lowered shoulder. He went up and over and landed behind the lefthand batter’s box. The umpire lifted his fist in the

out

sign. Then Anderson started to yell and grab his ankle. I could hear it from the far end of the dugout, so you know it must have been good yelling, because those Opening Day fans were roaring like a force-ten gale. I could see that Anderson’s left pants cuff was turning red, and blood was oozing out between his fingers.

Can I have a drink of water? Just pour some out of that plastic pitcher, would you? Plastic pitchers is all they give us for our rooms, you know; no glass pitchers allowed in the zombie hotel.