Blockade Billy (5 page)

Authors: Stephen King

Tags: #King; Stephen - Prose & Criticism, #Horror, #General, #Fiction - General, #Suspense, #Horror - General, #Fiction, #Sports

“I don’t get you.”

“If you popped and went flat like a bad tire, The Doo wouldn’t give much of a shit. He’d just find himself a brand new lucky charm.”

“You shouldn’t talk like that! Him and me’s friends!”

“I’m your friend, too. More important, I’m one of the coaches on this team. I’m responsible for your welfare, and I’ll talk any goddam way I want, especially to a rook. And you’ll listen. Are you listening?”

“I’m listening.”

I’m sure he was, but he wasn’t looking; he’d cast his eyes down and sullen red roses were blooming on those smooth little-boy cheeks of his.

“I don’t know what kind of a rig you’ve got under that Band-Aid, and I don’t want to know. All I know is I saw it in the first game you played for us, and somebody got hurt. I haven’t seen it since, and I don’t want to see it today. Because if you got caught, it’d be

you

caught. Not The Doo.”

“I just cut myself,” he says, all sullen.

“Right. Shaving. But I don’t want to see it on your finger when you go out there. I’m looking after your own best interests.”

Would I have said that if I hadn’t seen Joe so upset he was crying? I like to think so. I like to think I was also looking after the best interests of the game, which I loved then and now. Virtual Bowling can’t hold a candle, believe me.

I walked away before he could say anything else. And I didn’t look back. Partly because I didn’t want to see what was under the Band-Aid, mostly because Joe was standing in his office door, beckoning to me. I won’t swear there was more gray in his hair, but I won’t swear there wasn’t.

I came into the office and closed the door. An awful idea occurred to me. It made a kind of sense, given the look on his face. “Jesus, Joe, is it your wife? Or the kids? Did something happen to one of the kids?”

He started, like I’d just woken him out of a dream. “Jessie and the kids are fine. But George…oh

God

. I can’t believe it. This is such a mess.” And he put the heels of his palms against his eyes. A sound came out of him, but it wasn’t a sob. It was a laugh. The most terrible fucked-up laugh I ever heard.

“What is it? Who called you?”

“I have to think,” he says—but not to me. It was himself he was talking to. “I have to decide how I’m going to…” He took his hands off his eyes, and he seemed a little more like himself. “You’re managing today, Grannie.”

“Me?

I can’t manage! The Doo’d blow his stack! He’s going for his two hundredth again, and—”

“None of that matters, don’t you see? Not now.”

“What—”

“Just shut up and make out a lineup card. As for that kid…” He thought, then shook his head. “Hell, let him play, why not? Shit, bat him fifth. I was gonna move him up, anyway.”

“Of course he’s gonna play,” I said. “Who else’d catch Danny?”

“Oh, fuck Danny Dusen!” he says.

“Cap—Joey—tell me what happened.”

“No,” he says. “I got to think about it first. What I’m going to say to the guys. And the reporters!” He slapped his brow as if this part of it had just occurred to him.

“Those

overbred assholes! Shit!” Then, talking to himself again: “But let the guys have this game. They deserve that much. Maybe the kid, too. Hell, maybe he’ll bat for the cycle!” He laughed some more, then went upside his own head to make himself stop.

“I don’t understand.”

“You will. Go on, get out of here. Make any old lineup you want. Pull the names out of a hat, why don’t you? It doesn’t matter. Only make sure you tell the umpire crew chief you’re running the show. I guess that’d be Wenders.”

I walked down the hall to the umpire’s room like a man in a dream and told Wenders that I’d be making out the lineup and managing the game from the third base box. He asked me what was wrong with Joe, and I said Joe was sick.

That was the first game I managed until I got the Athletics in ’63, and it was a short one, because as you probably know if you’ve done your research, Hi Wenders ran me in the sixth. I don’t remember much about it, anyway. I had so much on my mind that I felt like a man in a dream. But I did have sense enough to do one thing, and that was to check the kid’s right hand before he ran out on the field. There was no Band-Aid on the second finger, and no cut, either. I didn’t even feel relieved. I just kept seeing Joe DiPunno’s red eyes and haggard mouth.

That was Danny Doo’s last good game ever, and he never did get his two hundred. He tried to come back in ‘58, but it was no good. He claimed the double vision was gone and maybe it was true, but he couldn’t hardly get the pill over the plate anymore. No spot in Cooperstown for Danny. Joe was right: that kid did suck luck.

But that afternoon Doo was the best I ever saw him, his fastball hopping, his curve snapping like a whip. For the first four innings they couldn’t touch him at all. Just wave the stick and take a seat, fellows. He struck out six and the rest were infield ground-outs. Only trouble was, Kinder was almost as good. We’d gotten one lousy hit, a two-out double by Harrington in the bottom of the third.

Now it’s the top of the fifth. The first batter goes down easy. Then Walt Dropo comes up, hits one deep into the left field corner, and takes off like a bat out of hell. The crowd saw Harry Keene still chasing the ball while Dropo’s legging for second, and they understood it could be an inside-the-park job. The chanting started. Only a few voices at first, then more and more. Getting deeper and louder. It put a chill up me from the crack of my ass to the nape of my neck.

“Bloh-KADE! Bloh-KADE! Bloh-KADE!”

Like that. The orange signs started going up. People were on their feet and holding them over their heads. Not waving them like usual, just holding them up. I have never seen anything like it.

“Bloh-KADE! Bloh-KADE! Bloh-KADE!”

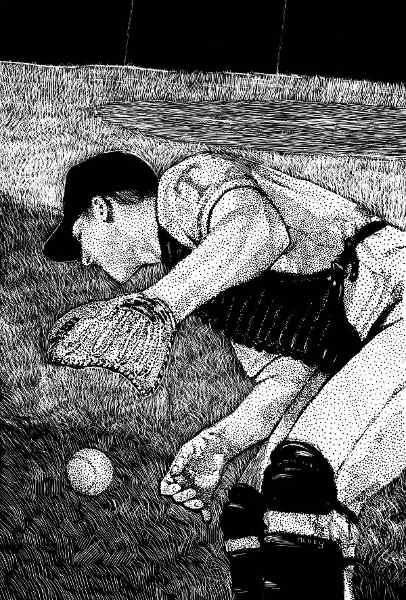

At first I thought there wasn’t a snowball’s chance in hell; by then Dropo’s steaming for third with all the stops pulled out. But Keene pounced on the ball and made a perfect throw to Barbarino at short. The rook, meanwhile, is standing on the third-base side of home plate with his glove held out, making a target, and Si hit the goddam pocket.

The crowd’s chanting. Dropo’s sliding, spikes up. The kid don’t mind; he goes on his knees and dives over em. Hi Wenders was where he was supposed to be—that time, at least—leaning over the play. A cloud of dust goes up…and out of it comes Wenders’s upraised thumb.

“Yerrrr…OUT!”

Mr. King, the fans went nuts. Walt Dropo did, too. He was up and dancing around like a coked-up kid at a record hop. He couldn’t believe it.

The kid was scraped halfway up his left forearm, not bad, just bloodsweat, but enough for old Bony Dadier—he was our trainer—to come out and slap a Band-Aid on it. So the kid got his Band-Aid after all, only this one was legit. The fans stayed on their feet during the whole medical consultation, waving their ROAD CLOSED signs and chanting

“Bloh-KADE! Bloh-KADE!”

like they wouldn’t ever get enough of it.

The kid didn’t seem to notice. He was in another world. He was the whole time he was with the Titans, now that I think of it. He just put on his mask, went back behind the plate, and squatted down. Business as usual. Bubba Phillips came up, lined out to Lathrop at first, and that was the fifth.

When the kid came up in the bottom of the inning and struck out on three pitches, the crowd still gave him a standing O. That time he noticed, and tipped his cap when he went back to the dugout. Only time he ever did it. Not because he was snotty but because…well, I already said it. That other world thing.

Okay, top of the sixth. Over fifty years later and I still get a red ass when I think of it. Kinder’s up first and loops out to third, just like a pitcher should. Then comes Luis Aparicio, Little Louie. The Doo winds and fires. Aparicio fouls it off high and lazy behind home plate, on the third base side of the screen. The kid throws away his mask and sprints after it, head back and glove out. Wenders trailed him, but not close like he should have done. He didn’t think the kid had a chance. It was lousy goddam umping.

The kid’s off the grass and on the track, by the low wall between the field and the box seats. Neck craned. Looking up. Two dozen people in those first- and second-row box seats also looking up, most of them waving their hands in the air. This is one thing I don’t understand about fans and never will. It’s a fucking

baseball

, for the love of God! An item that sold for seventy-five cents back then. Everybody knew it. But when fans see one in reach at the ballpark, they turn into fucking Danny Doo in order to get their hands on it. Never mind standing back and letting the man trying to catch it—

their

man, and in a tight ballgame—do his job.

I saw it all. Saw it clear. That mile-high popup came down on our side of the wall. The kid was going to catch it. Then some long-armed bozo in one of those Titans jerseys they sold on the Esplanade reached over and ticked it so the ball bounced off the edge of the kid’s glove and fell to the ground.

I was so sure Wenders would call Aparicio out—it was clear interference—that at first I couldn’t believe what I was seeing when he gestured for the kid to go back behind the plate and for Aparicio to resume the box. When I got it, I ran out, waving my arms. The crowd started cheering me and booing Wenders, which is no way to win friends and influence people when you’re arguing a call, but I was too goddam mad to care. I wouldn’t have stopped if Mahatma Gandhi had walked out on the field butt-naked and urging us to make peace.

“Interference!”

I yelled.

“Clear as day, clear as the nose on your face!”

“It was in the stands, and that makes it anyone’s ball,” Wenders says. “Go on back to your little nest and let’s get this show on the road.”

The kid didn’t care; he was talking to his pal The Doo. That was all right. I didn’t care that he didn’t care. All I wanted at that moment was to tear Hi Wenders a fresh new asshole. I’m not ordinarily an argumentative man—all the years I managed the A’s, I only got thrown out of games twice—but that day I would have made Billy Martin look like a peacenik.

“You didn’t see it, Hi! You were trailing too far back! You didn’t see shit!”

“I wasn’t trailing and I saw it all. Now get back, Granny. I ain’t kidding.”

“If you didn’t see that long-armed sonofabitch—”

(Here a lady in the second row put her hands over her little boy’s ears and pursed up her mouth at me in an oh-you-nasty-man look.)

“—that long-armed sonofabitch reach out and tick that ball, you were goddam trailing! Jesus Christ!”

The man in the jersey starts shaking his head—who, me? not me!—but he’s also wearing a big embarrassed suckass grin. Wenders saw it, knew what it meant, then looked away. “That’s it,” he says to me. And in the reasonable voice that means you’re one smart crack from drinking a Rhinegold in the locker room. “You’ve had your say. Now you can either go back to the dugout or you can listen to the rest of the game on the radio. Take your pick.”

I went back to the dugout. Aparicio stood back in with a big shit-eating grin on his face. He knew, sure he did. And made the most of it. The guy never hit many home runs, but when The Doo sent in a changeup that didn’t change, Louie cranked it high, wide, and handsome to the deepest part of the park. Nosy Norton was playing center, and he never even turned around.

Aparicio circled the bases, serene as the

Queen Mary

coming into dock, while the crowd screamed at him, denigrated his relatives, and hurled hate down on Hi Wenders’s head. Wenders heard none of it, which is the chief umpirely skill. He just got a fresh ball out of his coat pocket and inspected it for dings and doinks. Watching him do that, I lost it entirely. I rushed out to home plate and started shaking both fists in his face.

“That’s your run, you fucking busher!”

I screamed.

“Too fucking lazy to chase after a foul ball, and now you’ve got an RBI for yourself! Jam it up your ass! Maybe you’ll find your glasses!”

The crowd loved it. Hi Wenders, not so much. He pointed at me, threw his thumb back over his shoulder, and walked away. The crowd started booing and shaking their ROAD CLOSED signs; some threw bottles, cups, and half-eaten franks onto the field. It was a circus.

“Don’t you walk away from me, you fatass blind lazy sonofabitching bastard!”

I screamed, and chased after him. Someone from our dugout grabbed me before I could grab Wenders, which I meant to do. I had lost touch with reality.

The crowd was chanting

“KILL THE UMP! KILL THE UMP! KILL THE UMP!”

I’ll never forget that, because it was the same way they’d been chanting

“Bloh-KADE! Bloh-KADE!”

“If your mother was here, she’d be throwing shit at you, too, you bat-blind busher!”

I screamed, and then they hauled me into the dugout. Ganzie Burgess, our knuckleballer, managed the last three innings of that horrorshow. He also pitched the last two. You might find that in the record-books, too. If there were any records of that lost spring.

The last thing I saw on the field was Danny Dusen and Blockade Billy standing on the grass between the plate and the mound. The kid had his mask tucked under his arm. The Doo was whispering in his ear. The kid was listening—he always listened when The Doo talked—but he was looking at the crowd, forty thousand fans on their feet, men, women, and children, yelling

KILL THE UMP, KILL THE UMP, KILL THE UMP

.