Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (16 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

George Hudson depicted coming off the rails. Caricaturists often showed him as a symbolic locomotive with a crown for a chimney.

Hudson broke the law and he breached business ethics, but there were many people who had been aware of this and had heard or seen no evil as long as the dividends kept rolling in. They then hypocritically and sanctimoniously rounded on the man when he was no longer coming up with the goods. A

scapegoat was needed and Hudson fitted the bill. He was by no means unique in the history of capitalism as a businessman who accumulated and wielded wealth and power while not being too fussy about the methods he employed to do so. Those who benefited were not too fussy either.

The ‘Railway Mania’ period was a financial bubble, and like other bubbles it was rooted in the ‘get-rich-quick’ ethos. Hudson did get rich quickly, but in doing so he enriched many others along the way. The bubble, however, was bound to burst and inevitably Hudson was undone when that happened.

The earlier railway companies with which Hudson was associated were nearly all set-up as the result of their own specific private Acts of Parliament, which laid out in considerable detail the powers and responsibilities of their directors and of the chairman. In 1845 the alliterative Companies Clauses Consolidation Act codified practice on such matters as the role of directors and the act was applied to all new statutory companies. Hudson could therefore never have said that he was unaware of his legal obligations and responsibilities.

Research has identified five definite cases where Hudson embezzled money from one or other of the railway companies of which he was the chairman, and has highlighted up to eight occasions when Hudson most certainly acted in breach of his responsibilities as a director. He was involved in the falsification of the accounts of several of his companies, in particular the Eastern Counties. Although one of his biographers says that Hudson ‘raised creative accounting to an art form’

1

he always argued that everything he did was intended to benefit the railway companies which he controlled. His ego and his compulsive desire for wealth and power meant that, like many other entrepreneurs, he found it hard to differentiate between what was simply in his own interests and that which might have – or actually did – benefit other people. Significantly Hudson was never prosecuted in a criminal court.

Other later buccaneering entrepreneurs such as Horatio Bottomley, Robert Maxwell and John Dolorean, for example, could also do no wrong when the force was with them but they too were eventually caught out. When that happened those people, who only the previous day had been singing their praises and turning a blind eye to their business practices, started trilling a very different song.

There are parallels to be drawn between Hudson and those bankers and other supposed financial high-flyers whose self-seeking activities came to light in the ‘credit crunch’. The reality is that most people knew that their activities, if not actually illegal, were fuelling a speculative boom which would have disastrous effects when it eventually collapsed. One day such people had the Midas touch. The next day, when the inevitable collapse had happened, the bankers found themselves being almost universally excoriated for their ‘greed’.

William Gladstone, a leading figure on the British political scene in the second half of the nineteenth century, ruminated on Hudson’s fall from grace while exhibiting some talent as a poetaster. There was much that he admired about Hudson’s energy and vision but he also knew about the man’s sharp practice and he circulated friends with a little verse to that effect. Hudson, he said:

… bamboozled the mob; he bamboozled the quality;

He led both through the quagmire of gross immorality.

2

With some vehemence Gladstone went on – rightly – to condemn the pious self-righteousness of those who apparently only discovered the man’s ethical shortcomings once he could no longer serve them up their unearned income.

The career of Hudson, his rise and fall, was the product of an economic and social system undergoing a particularly dynamic and volatile period in its evolution. The ‘Railway Mania’ encouraged human greed and fed off human gullibility. The railway promoters and managers of the nineteenth century were not noted for their moral scruples. They operated in a dog-eat-dog world and those who were successful – as Hudson was for many years – needed to be ahead of the field in the extent to which they were far-sighted, quick-thinking, ruthless, determined and decisive. If it is felt necessary to judge Hudson, it can only be within the context of the circumstances that produced him.

The Redpath Frauds

One of the most spectacular examples in the nineteenth century of fraud associated with the railways was the case of Leopold Redpath. In August 1856 Edmund Dennison, the chairman of the Great Northern Railway, had addressed a meeting of shareholders in a forthright, even bullish, fashion. Among other things he stated his utmost confidence in the honesty and probity of the company’s employees. In fact he was being somewhat economical with the truth, which was that a couple of years earlier some discrepancies had been discovered in the company’s books.

They related to differences, apparently not huge ones, between the amounts paid in dividends and the amount due to be paid on the stock registered. The company’s officer in charge of the share registration department was a lawyer by the name of Clerk who knew virtually nothing about this aspect of the company’s work. He was due to retire and before he did so he stated that he was confident that the matter could be safely left in the hands of his successor who just happened to be the aforementioned Redpath.

In fact Redpath had basically been doing Clerk’s job under the guise of helping him out and had become indispensable. He saw to it that he kept his

knowledge of the department’s work to himself. He had arrived at the Great Northern with glowing references. These, in fact, were forged. Redpath, who had once been declared bankrupt, had in fact left his previous employment under a cloud. Not to put too fine a point on it he had had his fingers in the till.

So we have Leopold Redpath in charge of the entire GNR’s stock and share register while he was creating fraudulent stocks and printing numbered stock certificates which were not included in the company’s books but were being sold through stockbrokers to eager investors. He sold so much bogus scrip that the company was paying out increasingly large amounts of money as dividends when it had never received the capital used to buy the shares in the first place. One of his subordinates had pointed out some discrepancies.

Redpath thanked him for his vigilance and promised that he would carry out an investigation. Understandably this investigation proceeded extremely slowly, but suspicion was building up that something fishy was going on, and at the next shareholder’s meeting Dennison announced to an enraged audience that because an employee had been selling forged shares the state of the company finances meant that there would be no dividends for that half-year.

When the inevitable happened and the police called at his home with a request that he help them with their enquiries Redpath was consuming a large cooked breakfast as though he had not a care in the world. He had the sense to co-operate fully with the process of the law. His character puzzled the authorities. They expected such a big-time swindler to be brash and ostentatious. Instead he was charming, modest and almost self-effacing. His only extravagance was the ownership of two houses, one in London and one in what was once described as ‘the Surrey stockbroker belt’, and the throwing of fine dinner parties at which many of society’s so-called elite would appear. Most of his ill-gotten gains he gave away to charity! People simply could not understand why a swindler should take such risks in order to benefit those less fortunate than himself.

However, his charitable works cut no ice with the court when he appeared at the Old Bailey in 1857. Redpath was sentenced to transportation for life and his assets, to the tune of

£

25,000 – then a very considerable sum – were sequestered and paid to the Great Northern as partial compensation for the loss they had incurred, a far greater sum estimated at

£

250,000. What is remarkable is that the frauds were so simple and blatant that a few minutes inspection of the GNR’s register of stocks at any time between 1848 and 1856 would have revealed that fraud was taking place. It is small wonder then that Redpath had kept his cards, or rather the GNR books, so close to his chest and for so long.

The Redpath affair severely shook public confidence in the financial management of the railway companies in general and the Great Northern in particular. A concomitant of this was the emergence of the professional accountant as a replacement for the willing, but often blatantly ignorant, amateur auditor of company accounts. Over the years many railway employees

found ways to embezzle the companies they worked for but their activities were small beer compared with those of Hudson and Redpath.

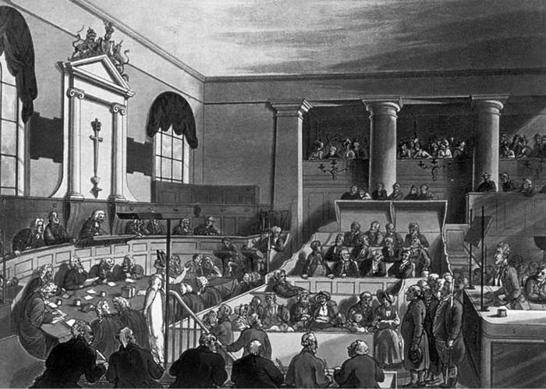

One of the courts in the Old Bailey. How many dramatic courtroom scenes have taken place in these surroundings?

Why Not Travel Free?

A consistent theme throughout the history of railway crime has been that of fare evasion. The Regulation of Railways Act of 1840 made travelling on the railway without a ticket a criminal offence. Additionally, railway companies could sue passengers in civil courts to recover the cost of the fares concerned. As early as 1905 at least one railway company displayed posters ‘naming and shaming’ passengers who had been successfully prosecuted for fare evasion. Some of the Train Operating Companies on the UK’s current scandalously denationalised railway ‘system’ have employed similar methods in recent years. Considerable ingenuity has been exercised by travellers in their attempts to avoid the cost of buying the appropriate ticket.

In the 1860s a most enterprising woman devised her own means of travelling around the British railway system largely free of charge. Her name seems to have been Nell and her first escapade was to be found apparently unconscious on a

train at Strood in north Kent. A doctor pronounced her dead and she was taken to the morgue whereupon she amazed everyone by sitting up and gazing around in confusion. The bemused authorities then moved her to the workhouse but she had only been there a few minutes when she brought tears to their eyes by saying that she had been on her way to see her brother but had been drugged and robbed on the train. She was now penniless – but did not remain so for long. The kind-hearted stationmaster heard this tale of woe and promptly issued her with a complementary ticket and gave her

£

5 from his own pocket.

Perhaps encouraged by her success as an actress and confidence-trickster, she later turned up pulling the same stunt and spinning a similar yarn at New Street station, Birmingham, at Shrewsbury and at Paddington. The latter was one stunt too many. The Great Western Railway police had heard about her and she was arrested. She served a three-month custodial sentence. It is amazing that she was able to feign death successfully and to pass examination by doctors so many times. Those privy to these actions agreed that she might have made a fortune on the stage.

Back in the 1890s a busker left a train carrying what was clearly a full-size harp, presumably his stock-in-trade, covered in green baize. Nothing wrong with that, you might say. An alert railway policeman thought that the man was making rather heavy weather of carrying the instrument. When the musician approached the barrier proffering the correct ticket for his journey, the officer decided to stop and question him, and in doing so discovered that the musician’s daughter, very small for her age but old enough to require a ticket, was huddling inside the package. The busker had not paid for her.

A group of young men travelling to Reading for the races did not bother to buy tickets but displayed some enterprise by jumping off at Reading while the train was slowing to a halt approaching the platform. Then they pretended to be ticket collectors and accosted passengers as they alighted from the train, demanding that they surrender their tickets. They did this brazenly enough to harvest more than enough tickets for all of them and then surrendered them as they passed through the barriers, leaving a sorry gaggle of bemused passengers to explain why they were without tickets. It all goes to show that if you have enough front, you can get away with anything.