Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (46 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

The main German actions of mid-1942 and onward, known as “Large Operations,” were actually

designed

to kill Belarusian civilians as well as Belarusian Jews. Unable to defeat the partisans as such, the Germans killed the people who might be aiding the struggle. Units were given a daily kill quota, which they generally met by encircling villages and shooting most or all of the inhabitants. They shot people over ditches or, in the case of Dirlewanger and those who followed his example, burned them in barns or blew them up by forcing them to clear mines. In autumn 1942 and early 1943, the Germans liquidated ghettos and whole villages associated with the partisans. In Operation Swamp Fever in September 1942, the Dirlewanger Brigade killed the 8,350 Jews still alive in the ghetto in Baranovichi, and then proceeded to kill 389 “bandits” and 1,274 “bandit suspects.” These attacks were led by Friedrich Jeckeln, the Higher SS and Police Chief for Reichskommissariat Ostland, the same man who had organized the mass shootings of Jews at Kamianets-Podilskyi in Ukraine and the liquidation of the Riga ghetto in Latvia. Operation Hornung of February 1943 began with the liquidation of the Slutsk ghetto, which is to say the shooting of some 3,300 Jews. In an area southwest of Slutsk the Germans killed about nine thousand more people.

42

By early 1943, the people of Belarus, especially the young men, were caught in a deadly competition between German forces and Soviet partisans that made nonsense of the ideologies of both sides. The Germans, lacking personnel, had recruited local men to their police forces (and, in the second half of 1942, to a “self-defense” militia). Many of these people had been communists before the war. The partisans, for their part, began in 1943 to recruit Belarusian policemen in the German service, since these men had at least some arms and training.

43

It was the battlefield failures of the Wehrmacht, rather than any local political or ideological commitment, that determined where Belarusians chose to fight, when they had a choice. The summer offensive of Army Group South failed, and the entire Sixth Army was destroyed in the Battle of Stalingrad. When news of the Wehrmacht’s defeat reached Belarus in February 1943, as many as twelve thousand policemen and militiamen left the German service and joined the Soviet partisans. According to one report, eight hundred did so on 23 February alone. This meant that some Belarusians who had killed Jews in the service of Nazis in 1941 and 1942 joined the Soviet partisans in 1943. More than this: the people who recruited these Belarusian policemen, the political officers among the partisans, were sometimes Jews who had escaped death at the hands of Belarusian policemen by fleeing the ghettos. Jews trying to survive the Holocaust recruited its perpetrators.

44

Only the Jews, or the few who remained in Belarus in 1943, had a clear reason to be on one side rather than the other. Since they were the Germans’ obvious and declared enemy in this war, and German enmity meant murder, they had every incentive to join the Soviets, despite the dangers of partisan life. For Belarusians (and Russians and Poles) the risks were more balanced; but the possibility of uninvolvement kept receding. For the Belarusians who ended up fighting and dying on one side or the other, it was very often a matter of chance, a question of who was in the village when the Soviet partisans or the German police appeared on their recruiting missions, which often simply involved press-ganging the young men. Since both sides knew that their membership was largely accidental, they would subject new recruits to grotesque tests of loyalty, such as killing friends or family members who had been captured fighting on the other side. As more and more of the Belarusian population was swept into the partisans or the various police and paramilitaries that the Germans hastily organized, such events simply revealed the essence of the situation: Belarus was a society divided against itself by others.

45

In Belarus, as elsewhere, local German policy was conditioned by general economic concerns. By 1943, the Germans were worried more about labor shortages than about food shortages, and so their policy in Belarus shifted. As the war against the Soviet Union continued and the Wehrmacht took horrible losses month upon month, German men had to be taken from German farms and factories and sent to the front. Such people then had to be replaced if the German economy was to function. Hermann Göring issued an extraordinary directive in October 1942: Belarusian men in suspicious villages were not to be shot but rather kept alive and sent as forced laborers to Germany. People who could work were to be “selected” for labor rather than killed—even if they had taken up arms against Germany. By now, Göring seemed to reason, their labor power was all that they could offer to the Reich, and it was more significant than their death. Since the Soviet partisans controlled ever more Belarusian territory, ever less food was reaching Germany in any case. If Belarusian peasants could not work for Germany in Belarus, best to force them to work in Germany. This was very grim reaping. Hitler made clear in December 1942 what Göring had implied: the women and children, regarded as less useful as labor, were to be shot.

46

This was a particularly spectacular example of the German campaign to gather forced labor in the East, which had begun with the Poles of the General Government, and spread to Ukraine before reaching this bloody climax in Belarus. By the end of the war, some eight million foreigners from the East, most of them Slavs, were working in the Reich. It was a rather perverse result, even by the standards of Nazi racism: German men went abroad and killed millions of “subhumans,” only to import millions of other “subhumans” to do the work in Germany that the German men would have been doing themselves—had they not been abroad killing “subhumans.” The net effect, setting aside the mass killing abroad, was that Germany became more of a Slavic land than it had ever been in history. (The perversity would reach its extreme in the first months of 1945, when surviving Jews were sent to labor camps in Germany itself. Having killed 5.4 million Jews as racial enemies, the Germans then brought Jewish survivors home to do the work that the killers might have been doing themselves, had they not been abroad killing.)

Under this new policy, German policemen and soldiers were to kill Belarusian women and children so that their husbands and fathers and brothers could be used as slave laborers. The anti-partisan operations of spring and summer 1943 were thus slavery campaigns rather than warfare of any recognizable kind. Yet because the slave hunts and associated mass murder were sometimes resisted by the Soviet partisans, the Germans did take losses. In May and June 1943 in Operations Marksman and Gypsy Baron (named after an opera and an operetta), the Germans aimed to secure railways in the Minsk region as well as workers for Germany. They reported killing 3,152 “partisans” and deporting 15,801 laborers. Yet they took 294 dead of their own: an absurdly low ratio of 1:10, if one assumed (wrongly) that reported partisan dead were actual partisans rather than (generally) civilians, but still a significant number.

47

In May 1943 in Operation Cottbus, the Germans sought to clear all partisans from an area about 140 kilometers north of Minsk. Their forces destroyed village after village by herding populations into barns and then burning the barns to the ground. On the following days, the local swine and dogs, now without masters, would be seen in villages with burned human limbs in their jaws. The official count was 6,087 dead; but the Dirlewanger Brigade alone reported fourteen thousand killed in this operation. The majority of the dead were women and children; about six thousand men were sent to Germany as laborers.

48

Operation Hermann, named for Hermann Göring, reached the extreme of this economic logic in summer 1943. Between 13 July and 11 August, German battle groups were to choose a territory, kill all of the inhabitants except for promising male labor, take all property that could be moved, and then burn everything left standing. After the labor selections among the local Belarusian and Polish populations, the Belarusian and Polish women, children, and aged were shot. This operation took place in western Belarus—in lands that had been invaded by the Soviet Union and annexed from Poland in 1939 before the German invasion that followed in 1941.

49

Polish partisans were also to be found in these forests, fighters who believed that these lands should be restored to Poland. Thus German anti-partisan actions here were directed against both the Soviet partisans (representing the power that had governed in 1939-1941) and the Polish underground (fighting for Polish independence and territorial integrity with the boundaries of 1918-1939). The Polish forces were part of the Polish Home Army, reporting to the Polish government in exile in London. Poland was one of the Allies, and so in principle Polish and Soviet forces were fighting together against the Germans. But because both the Soviet Union and Poland claimed these lands of western Soviet Belarus (from the Soviet perspective) or northeastern Poland (from the Polish), matters were not so simple in practice. Polish fighters found themselves trapped between lawless Soviet and German forces. Polish civilians were massacred by Soviet partisans when Polish forces did not subordinate themselves to Moscow. In Naliboki on 8 May 1943, for example, Soviet partisans shot 127 Poles.

50

Red Army officers invited Home Army officers to negotiate in summer 1943, and then murdered them on the way to the rendezvous points. The commander of the Soviet partisan movement believed that the way to deal with the Home Army was to denounce its men to the Germans, who would then shoot the Poles. Meanwhile, Polish forces were also attacked by the Germans. Polish commanders were in contact with both the Soviets and the Germans at various points, but could make a true alliance with neither: the Polish goal, after all, was to restore an independent Poland within its prewar boundaries. Just how difficult that would be, as Hitler’s power gave way to Stalin’s, was becoming clear in the Belarusian swamps.

51

The Germans called the areas cleared of populations in Operation Hermann and the succeeding operations of 1943 “dead zones.” People found in a dead zone were “fair game.” The Wehrmacht’s 45th Security Regiment killed civilians in Operation Easter Bunny of April 1943. Remnants of Einsatzgruppe D, dispatched to Belarus in spring 1943, contributed to this undertaking. They came from southern Russia and southern Ukraine, where the remnants of Army Group South were falling back after the defeat at Stalingrad. The task of Einstazgruppe D there had been to cover the German retreat by killing civilians wherever resistance had been reported. In Belarus, it was burning down villages where no resistance whatsoever was encountered, after taking whatever livestock it could. Einsatzgruppe D was no longer covering a withdrawal of the Wehrmacht, as it had been further south, but preparing for one.

52

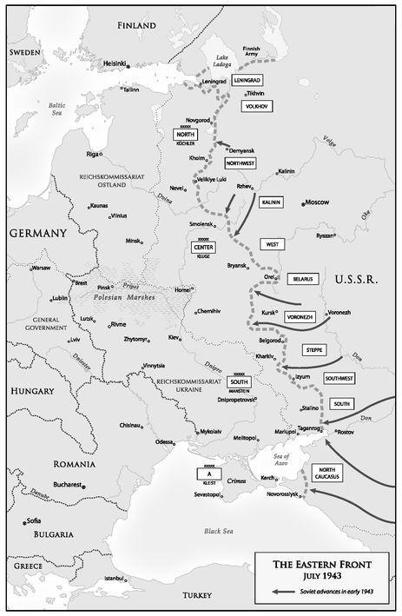

The resort to dead zones implied a recognition that Soviet power would soon return to Belarus. Army Group South (much reduced and fighting under other names) was in retreat. Army Group North still besieged Leningrad, pointlessly. Belarus itself was still behind the lines of Army Group Center, but not for long.

At various points during the German occupation of Belarus, it did dawn on some German military and civilian leaders that mass terror was failing, and that the Belarusian population had to be rallied by some means other than terror to support German rule if the Red Army was to be defeated. This was impossible. As everywhere in the occupied Soviet Union, the Germans had succeeded in making most people wish for a return of Soviet rule. A German propaganda specialist sent to Belarus reported that there was nothing that he could possibly tell the population.

53

The German-backed Russian Popular Army of Liberation (RONA in a Russian abbreviation) was the most dramatic attempt to gain local support. It was led by Bronislav Kaminskii, a Soviet citizen of Russian nationality and Polish and perhaps German descent, who had apparently been sent to a Soviet special settlement in the 1930s. He presented himself as an opponent of collectivization. The Germans permitted him an experiment in local self-government in the town of Lokot, in northwestern Russia. There Kaminskii was placed in charge of anti-partisan operations, and locals were indeed allowed to keep more of the grain that they produced. As the war turned against the Germans, Kaminskii and his entire apparatus were dispatched from Russia to Belarus, where they were supposed to play a similar role. Kaminskii was ordered to fight the Soviet partisans in Belarus, but he and his group could barely protect themselves in their home base. Understandably, the Belarusian locals regarded RONA as foreigners who were taking land while speaking about property rights.

54