Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (48 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

The changing mission of the Trawniki men, like the changing use of Bełżec, revealed the transformation of Hitler’s utopias. In Globocnik’s initial scheme, these men were to serve as policemen, under German command, in the conquered Soviet Union. Since the Soviet Union was not in fact conquered, the Trawniki men could be prepared for another special task: operating the facilities where the Jews of Poland would be gassed. The Trawniki men knew nothing of this general design when they were recruited, and had no political or personal stake in this policy. For them, Poland was a foreign country, and its Jews were a foreign people. They presumably had a strong interest in keeping their jobs; their recruitment rescued them from a likely death by starvation. Even if they somehow had the courage to defy the Germans anyway, they knew that they could not safely return to the Soviet Union. In leaving the Dulags and Stalags they had stamped themselves as German collaborators.

In December 1941 the Trawniki men, wearing black uniforms, assisted in the construction of a ramp and a rail spur, which would allow communication by train to Bełżec. Soviet citizens were providing the labor for a German killing policy.

5

Bełżec was not to be a camp. People spend the night at camps. Bełżec was to be a death factory, where Jews would be killed upon arrival.

There was a German precedent for such a facility, where people arrived under false pretences, were told that they needed to be showered, and then were killed by carbon monoxide gas. Between 1939 and 1941 in Germany, six killing facilities had been used to murder the handicapped, the mentally ill, and others deemed “unworthy of life.” After a test run of gassing the Polish handicapped in the Wartheland, Hitler’s chancellery organized a secret program to kill German citizens. It was staffed by doctors, nurses, and police chiefs; one of its main organizers was Hitler’s personal doctor. The medical science of the mass murder was simple: carbon monoxide (CO) binds much better than oxygen (O

2

) to the hemoglobin in blood, and thereby prevents red blood cells from performing their normal function of bringing oxygen to tissues. The victims were brought in for ostensible medical examinations, and then led to “showers,” where they were asphyxiated by carbon monoxide released from canisters. If the victims had gold teeth, they were marked beforehand with a chalk cross on their backs, so that these could be extracted after their death. Children were the first victims, the parents receiving mendacious letters from doctors about how they had died during treatment. Most of the victims of the “euthanasia” program were non-Jewish Germans, although German Jews with disabilities were simply killed without any screening whatsoever. At one killing facility, the personnel celebrated the ten-thousandth cremation by bedecking a corpse with flowers.

6

The declared end of the “euthanasia” program coincided with Globocnik’s mission to develop a new technique for the gassing of Polish Jews. By August 1941, when Hitler called the program to a halt for fear of domestic resistance, it had registered 70,273 deaths, and created a model of deceptive killing by lethal gas. The suspension of the “euthanasia” program left a group of policemen and doctors with certain skills but without employment. In October 1941, Globocnik summoned a group of them to the Lublin district to run his planned death facilities for Jews. Some 92 of the 450 or so men who would serve Globocnik in the task of gassing the Polish Jews had prior experience in the “euthanasia” program. The most important of them was Christian Wirth, who had overseen the “euthanasia” program. As the head of Hitler’s chancellery put it, “a large part of my organization” was to be used “in a solution to the Jewish question that will extend to the ultimate possible consequences.”

7

Globocnik was not the only one to exploit the experience of the “euthanasia” crews. A gassing facility at Chełmno, in the Wartheland, also exploited the technical experience of the “euthanasia” program. Whereas Globocnik’s Lublin district was the experimental site for the destructive side of Himmler’s program for “strengthening Germandom,” Arthur Greiser’s Wartheland was the site of most actual deportation: hundreds of thousands of Poles were shipped to the General Government, and hundreds of thousands of Germans arrived from the Soviet Union. Greiser faced the same problem as Hitler, on a smaller scale: after all the movement, the Jews remained, and by late 1941 no plausible site for deportation was evident. Greiser did manage to deport a few thousand Jews to the General Government, but these were replaced by Jews deported from the rest of Germany.

8

The head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) in Greiser’s regional capital Poznań had proposed a solution on 16 July 1941: “There is the danger this winter that the Jews can no longer all be fed. It is to be seriously considered whether the most humane solution might not be to finish off those Jews not capable of working by some sort of fast-working preparation. This would be in any event more pleasant than letting them starve.” The “fast-working preparation” was carbon monoxide, as used in the “euthanasia” program. A gas van was tested on Soviet prisoners of war in September 1941; thereafter gas vans were used in occupied Belarus and Ukraine, especially to kill children. The killing machine at Chełmno was a parked gas van, operated under the supervision of Herbert Lange, who had gassed the handicapped in the “euthanasia” program. As of 5 December, Germans were using the Chełmno facility to kill Jews in the Wartheland. Some 145,301 Jews were killed at Chełmno in 1941 or 1942. Chełmno was operative until the Jewish population of the Wartheland was reduced, essentially, to a very functional labor camp inside the Łódź ghetto. But the killing paused, in early April: just as the killing in the Lublin district was beginning.

9

Bełzec was to be a new model, more efficient and more durable than Chełmno. Most likely in consultation with Wirth, Globocnik decided to build a permanent facility where many people could be gassed at once behind walls (as with the “euthanasia” program), but one where carbon monoxide gas could be reliably generated from internal combustion engines (as with the gas vans). Rather than parking a vehicle, as at Chełmno, this meant removing the engine from a vehicle, linking it with pipes to a purpose-built gas chamber, surrounding that gas chamber with fences, and then connecting the death factory to population centers by rail. Such were the simple innovations of Bełżec, but they were enough.

10

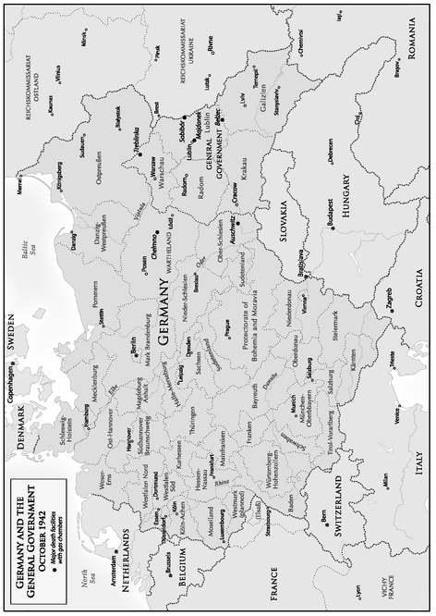

The Nazi leadership had always understood the Polish Jews to be at the heart of the Jewish “problem.” The German occupation had divided Jews who had been Polish citizens into three different political zones. As of December 1941, some three hundred thousand Polish Jews were living in the Wartheland and other Polish lands annexed to Germany. They were now subject to gassing at Chełmno. The 1.3 million or so Polish Jews on the eastern side of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line were subject to shooting from June 1941, and most of their number would be killed in 1942. The largest group of Polish Jews under German occupation were those in ghettos in the General Government. Until June 1941, the General Government held half of the prewar population of Polish Jews, about 1,613,000 people. (When a Galicia district was added after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the number of Jews in the General Government reached about 2,143,000. Those half-million or so Jews in Galicia, east of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, were subject to shooting.)

11

When Himmler and Globocnik began, in March 1942, to kill the Polish Jews of the General Government, they were undertaking an unambiguous policy to destroy the major Jewish population of Europe. On 14 March 1942 Himmler spent the night in Lublin and spoke with Globocnik. Two days later the Germans began the deportation of Jews from the Lublin district to Bełżec. On the night of 16 March, about 1,600 Jews who lacked labor documents were rounded up in Lublin, shipped away, and gassed. In the second half of March 1942 the Germans began to clear the Lublin district of Jews, village by village, town by town. Hermann Höfle, Globocnik’s lieutenant for “resettlement,” led a staff that developed the necessary techniques. Jews from smaller ghettos were ordered to larger ones. Then Jews with dangerous associations, suspected communists, and Polish Army veterans, were shot. In the final preparatory step, the population was filtered and younger men and others deemed suitable for labor were given new papers.

12

West of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, the Germans arranged matters so that they did less of the actual killing themselves. The institutions of the ghetto, its Judenrat and Jewish police force, were turned toward its destruction. Globocnik’s staff would begin an action in a given town or city by contacting the local Security Police, and then assemble a force of German policemen. If the Germans had at their disposal a Jewish police force, as they did in communities of any size, Jewish policemen were then required to do the bulk of the actual work of assembling their fellow Jews for transports. In cities, the Jewish police far outnumbered the Germans from whom they took orders. Since they had no firearms, they could only use force against fellow Jews. Sometimes Trawniki men were also available to help.

13

The German police ordered the Jewish police to assemble the Jewish population at a given assembly point by a certain time. At first, Jews were often lured to the collection point with promises of food or more attractive labor assignments “in the east.” Then, in roundups that took several days, the Germans and the Jewish police would blockade particular blocks or particular houses, and force their inhabitants to go to a collection point. Germans shot small children, pregnant women, and the handicapped or elderly on the spot. In larger towns and cities where more than one roundup was necessary, these measures were repeated with increasing violence. The Germans were aiming for daily quotas to fill trains, and would sometimes pass on quotas to the Jewish police who were responsible (at the risk of their own positions and thus lives) for filling them. The ghetto was sealed during and also after the action, so that the German police could plunder without hindrance from the local population.

14

Once the Jews reached Bełżec, they were doomed. They arrived unarmed to a closed and guarded facility, with little chance of understanding their situation, let alone resisting the Germans and the armed Trawniki men. Much like the patients at the “euthanasia” centers, they were told that they had to enter a certain building in order to be disinfected. They were required to remove their clothes and discard their valuables, on the explanation that these too would be disinfected and returned. Then they were marched, naked, into chambers that were pumped full of carbon monoxide. Only two or three Jews who disembarked at Bełżec survived; about 434,508 did not. Wirth commanded the facility through the summer of 1942, and seems to have excelled in his duties. Thereafter he would serve as general inspector of Bełżec and the two other facilities that would be built on the same model.

15

This system worked nearly to perfection in the Lublin district of the General Government. Deportations to Bełżec from the Cracow district began slightly later, with similar results. Jews from the Galicia district suffered from the overlap of two German killing methods: beginning in summer 1941 they were shot; and then from March 1942 they were gassed at Bełżec. Galicia was to the east of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, and so Jews there were subject to shooting; but it had been added to the General Government, so its Jews were also subject to gassing. Thomas Hecht, a Galician Jew who survived, recounted some of the ways Jews might die in Galicia: two aunts, an uncle, and a cousin were gassed at Bełżec; his father, one of his brothers, an aunt, an uncle, and a cousin were shot; his other brother died at a labor camp.

16