Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (54 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

In Berlin, Himmler was furious. On 16 February 1943 he decided that the ghetto must be destroyed not only as a society but as a physical place. That neighborhood of Warsaw was of no value to the racial masters, since houses that had been (as Himmler put it) “used by subhumans” could never be suitable for Germans. The Germans planned an assault on the ghetto for 19 April. Again, its immediate purpose was not to kill all the Jews but, rather, to redirect their labor power to concentration camps, and then to destroy the ghetto. Himmler had no doubt that this would work. He was thinking ahead to the uses of the site: in the long term it would become a park, in the meantime a concentration camp until the war was won. Jewish laborers from Warsaw would be worked to death at other sites.

18

Right before the planned assault on the Warsaw ghetto, German propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels made his own special contribution. In April 1943, the Germans had discovered Katyn, one of the sites where the NKVD had murdered Polish prisoners of war in 1940. “Katyn,” declared Goebbels, “is my victory.” He chose 18 April 1943 to announce the discovery of the corpses of Polish officers. Katyn could be used to create problems between Soviets and Poles, and between Poles and Jews. Goebbels expected, and quite rightly, that the evidence that the Soviet secret police had shot thousands of Polish officers would make cooperation between the Soviet Union and the Polish government-in-exile more problematic. The two were uneasy allies at best, and the Polish government had never gotten a satisfactory reply from the Soviets about those missing officers. Goebbels also wished to use Katyn to display the anti-Polish policies of the supposedly Jewish leadership of the Soviet Union, and thus to alienate Poles from Jews. So went the propaganda on the eve of the German attack on the Warsaw ghetto.

19

The Jewish Combat Organization had made its plans as well. The Germans’ abortive January 1943 ghetto clearing had confirmed Jewish leaders’ expectation that a final reckoning was coming. The sight of dead Germans on the streets had broken the barrier of fear, and the second transfer of arms from the Home Army had also increased confidence. The Jews in the ghetto assumed that any further deportation would be straight to the gas chambers. This was not quite true; if they had not fought they would have been sent, most of them, to concentration camps as laborers. But only for the next few months. The surviving Warsaw Jews were fundamentally correct in their judgments. The “last stage of resettlement,” as one of their number had written, “is death.” Few of them would die in Treblinka, but almost all of them would die before the end of 1943. They were right to think that resistance could scarcely reduce their chances of survival. If the Germans won the war, they would kill remaining Jews within their empire. If they continued to lose the war, the Germans would kill Jewish laborers as a security risk as the Soviets advanced. A distant but approaching Red Army meant a moment more of life, as the Germans extracted labor. But a Red Army at the doorstep would mean the gas chamber or a gunshot.

20

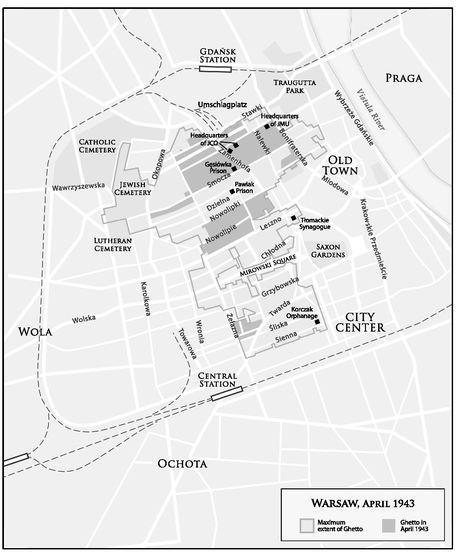

It was Jewish certainty of common death that enabled cooperative Jewish resistance. So long as German policy had allowed Jews to believe that some would survive, individuals could hope that they would be the exceptions, and social divisions were inevitable. Now that German policy had convinced all remaining Jews in the Warsaw ghetto that they would die, Jewish society in the ghetto evinced an impressive unity. Between January and April 1943, Jews built themselves countless bunkers in cellars, sometimes linked by secret passages. The Jewish Combat Organization established its command structure. The overall commander was Mordechai Anielewicz; the three leaders in three defined sectors of the ghetto were Marek Edelman, Izrael Kanał, and Icchak Cukierman (who was replaced at the last moment by Eliezer Geller). It bought more arms and trained its members in their use. Some Jews, working in German armaments factories, managed to steal materials for improvised explosives. The Jewish Combat Organization learned of German plans to attack the ghetto a day in advance, and so when the Germans came, all were ready.

21

Some members of the Home Army, in surprise and in admiration, called it the “Jewish-German War.”

22

When the SS, Order Police, and Trawniki men entered the ghetto on 19 April 1943, they were repulsed by sniper fire and Molotov cocktails. They actually had to retreat from the ghetto. German commanders reported twelve men lost in battle. Mordechai Anielewicz wrote a letter to his Jewish Combat Organization comrade Icchak Cukierman, who at the time was beyond the ghetto walls: the Jewish counterattack “had surpassed our wildest dreams: the Germans ran away from the ghetto twice.” The Home Army press wrote of “immeasurably strong and determined armed resistance.”

23

The right-wing Jewish Military Union seized the heights of the tallest building in the ghetto and raised two flags: the Polish and the Zionist, white eagle and yellow star. Its units would fight with great determination near their headquarters, at Muranowska Square. On 20 April, the SS and Police Leader for Warsaw district, Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg, was relieved of duty. His replacement, Jürgen Stroop, took a telephone call from an enraged Himmler: “You must take down those flags at any cost!” The Germans did take them down, on 20 April (Hitler’s birthday), although they took losses of their own in doing so. On that day the Germans managed to enter the ghetto and remain, although their prospects for clearing its population seemed dim. Most Jews were in hiding, and many were armed. The Germans would have to develop new tactics.

24

From the first day of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Jews were killed in battle. Jews who were unable to work, when discovered by the Germans, were also killed. The Germans knew that they had no use for the people whom they found at the hospital on Gęsia Street, the last Jewish hospital in Warsaw. Marek Edelman found there dozens of corpses in hospital gowns. In the gynecology and obstetrics sections, the Germans murdered pregnant women, women who had just given birth, and their babies. At the corner of Gęsia and Zamenhof Streets, someone had placed a live infant at the naked breast of a dead woman. Although Jewish resistance looked like a war from the outside, the Germans were not following any of the laws and customs of war inside the ghetto walls. The simple existence of Jewish subhumans was essentially criminal to the SS, and their resistance was an infuriating act that justified any response.

25

Stroop decided that the only way to clear the bunkers and houses was to burn them. Since Himmler had already ordered the physical destruction of the ghetto, burning down its residences was no loss. Indeed, since Himmler had not known just how the demolition was to be accomplished, the fires solved two Nazi problems at once. On 23 April 1943, Stroop’s men began to burn down the buildings of the ghetto, block by block. The Wehrmacht played little role in the combat, but its engineers and flamethrowers were used in the destruction of the residences and bunkers. Edelman recalled “enormous firestorms that closed whole streets.” Suffocating Jews had no choice but to flee their bunkers. As one survivor remembered: “we wanted to get killed by shooting rather than by burning.” Jews trapped on the upper floors of buildings had to jump. The Germans took many prisoners with broken legs. These people were interrogated and then shot. The only way that Jews could escape the arson was to flee from one bunker to another during the day, or from one house to another during the night. For several days the SS would not feel safe moving through the streets of the ghetto in darkness, so Jewish fighters and civilians could use the dark hours to move and regroup. But so long as they could not stop the burning, their days were numbered.

26

The Germans had attacked the ghetto on 19 April 1943, the eve of Passover. Easter fell on the following Sunday, the 25th. The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz recorded the Christian holiday from the other side of the ghetto walls, recalling in his poem “Campo di Fiori” that people rode the carousel at Krasiński Square, just beyond the ghetto wall, as the Jews fought and died. “I thought then,” wrote Miłosz, “of the loneliness of the dying.” The merry-go-round ran every day, throughout the uprising. It became the symbol of Jewish isolation: Jews died in their own city, as Poles beyond the walls of the ghetto lived and laughed. Many Poles did not care what happened to the Jews in the ghetto. Yet others were concerned, and some tried to help, and a few died trying.

27

A full year before the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began, the Home Army had alerted the British and the Americans to the gassing of Polish Jews. The Home Army had passed on reports of the death facility at Chełmno, and Polish authorities had seen to it that they reached the British press. The western Allies took no action of any consequence. In 1942 the Home Army had informed London and Washington of the deportations from the Warsaw ghetto and the mass murder of Warsaw Jews at Treblinka. To be sure, these events were always presented by the Polish government as an element in the larger tragedy of the citizens of Poland. The key information, however, was communicated. Poles and Jews alike had believed, wrongly, that publicizing the deportations would bring them to a halt. The Polish government had also urged the Allies to respond to the mass killing of Polish citizens (including Jews) by killing German civilians. Again, Britain and the United States did not act. The Polish president and the Polish ambassador to the Vatican urged the pope to speak out about the mass murder of Jews, to no effect.

28

Among the western Allies, only Polish authorities took direct action to halt the killing of Jews. By spring 1943 Żegota was assisting about four thousand Jews in hiding. The Home Army announced that it would shoot Poles who blackmailed Jews. On 4 May, as the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto fought on, Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski issued an appeal: “I call on my countrymen to give all help and shelter to those being murdered, and at the same time, before all humanity, which has for too long been silent, I condemn these crimes.” As Jews and Poles alike understood, the Warsaw command of the Home Army could not have saved the ghetto, even if it had devoted all of its troops and weapons to that purpose. It had, at that point, almost no combat experience itself. Nevertheless, seven of the first eight armed operations carried out by the Home Army in Warsaw were in support of the ghetto fighters. Two Poles died at the very beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, trying to breach the ghetto walls. Several further attempts to breach the walls of the ghetto failed. All in all, the Home Army made some eleven attempts to help the Jews. Soviet propagandists, seeing an opportunity, claimed that the Home Army denied aid to the fighting ghetto.

29

Aryeh Wilner, whom the Poles of the Home Army knew as Jurek, was an important liaison between the Jewish Combat Organization and the Home Army. He was killed during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, but not before passing on an important message, almost a legend in itself, to his Polish contacts. It was he who spread the description of Jewish resistance that the Home Army would approve and itself publish: that the Ghetto Uprising was not about preserving Jewish life but about rescuing human dignity. This was understood in Polish Romantic terms: that deeds should be judged by their intentions rather than their outcomes, that sacrifice ennobles and sacrifice of life ennobles eternally. Often overlooked or forgotten was the essence of Wilner’s point: Jewish resistance in Warsaw was not only about the dignity of the Jews but about the dignity of humanity as such, including those of the Poles, the British, the Americans, the Soviets: of everyone who could have done more, and instead did less.

30

Shmuel Zygielbojm, the representative of the Bund to the Polish government-in-exile in London, knew that the ghetto was going up in flames. He had a clear idea of the general course of the Holocaust from Jan Karski, a Home Army courier who had brought news of the mass murder to Allied leaders in 1942. Zygielbojm would not have known the details, but he grasped the general course of events, and made an effort to define it for the rest of the world. In a careful suicide note of 12 May 1943, addressed to the Polish president and prime minister but intended to be shared with other Allied leaders, he wrote: “Though the responsibility for the crime of the murder of the entire Jewish nation rests above all upon the perpetrators, indirect blame must be borne by humanity itself.” The next day he burned himself alive in front of the British parliament, joining in, as he wrote, the fate of his fellow Jews in Warsaw.

31