Bluestockings (10 page)

Authors: Jane Robinson

Such comparisons encouraged reform, and led to progress. Everywhere, that is, but at Oxford and Cambridge. There, degrees for women remained elusive and apparently undeserved.

Admission was one thing; assimilation quite another. The German visitor’s observations prove that. Publicly, this new

species must be seen to be coping well. Jessie Emmerson of St Hugh’s was well aware of this: ‘So greatly did the responsibility of keeping up the honour and dignity of my sex press upon me,’ she confided, ‘that I hardly dared address a word to anyone around me. One false step – and – for all I knew – they would never allow another woman student…’

15

Pioneers of LMH made the same point, reminding the first residents that ‘nothing should happen in any way to make college authorities anxious, or to strengthen the very decided initial prejudice of the undergraduates against the supposed “bluestockings”… invading Oxford’.

16

Society at large, and university communities in particular, needed persuading that this hazardous innovation was working well. So did the parents paying for it. It was therefore in students’ interests to present as appealing a picture of their university life as possible in letters home. What appealed to Bessie Macleod’s family was obviously flat-out activity. Bessie describes a typical day at Girton for them, during her first term in October 1881. It starts at 6.30, with the shriek of an alarm clock, and Bessie fumbling about in the dark, with chilblained fingers, for a candle. Once it’s lit, she wraps up warmly and takes it through to her en-suite study to do an hour’s Latin. She has to pick her way through the debris of last night’s revels (she had a cocoa party, and her guests brought cake). The ‘Gyp’, or maid, will clear that up later, after she has delivered Bessie her daily ration of coal for the fire and a jug of hot water for washing.

At eight o’clock it’s prayers. As a fresher, Bessie has to sit at the back, which means she is last to breakfast. By the time she gets to the dining hall, there is nothing left but an unalluring cocktail of cold ham and treacle. She has a cup of tea instead, and making sure there are no tutors around to see, sprints straight back upstairs to continue her Latin prose,

which she has until 10.00 a.m. to complete. Sprinting is not what Girtonians do.

She rushes her work to the post room (the ink still wet) just in time for it to be bundled up and dispatched to a tutor down the road in Cambridge. There are several postal collections and deliveries a day, and it is quicker to mail essays and assignments than physically to take them. The rest of the morning is spent on theology, Greek, and maths.

Lunch is at 1.00 p.m., and to signal that she is not in the mood for conversation, Bessie arms herself with a stern expression and a book. Neither works: with awful inevitability, Girton’s dreariest daughter makes straight for her. The college population is encouraged to take a constitutional stroll around the grounds after lunch; at two o’clock Bessie has a lecture, and the rest of the afternoon evaporates in work.

The menu for dinner at six o’clock is unpromising: fish, mutton casserole, potatoes, turnips, and sago pudding. Feeling weary and weighed down by stodge, Bessie looks forward to a little free time – and then remembers tonight is fire drill night.

Every women’s college in the country had its own fire brigade, unless it happened to be in a city centre (which very few were). In Bessie’s era there was still candlelight; surprisingly soon, smoking was to be allowed in students’ rooms, and open fires were everywhere right up to the Second World War. Girton especially relied on its brigade: it would be ages before the Cambridge fire fighters got there on their horse-drawn cart in an emergency. The brigade boasted buckets, hoses, and a portable chute for dramatic bedroom rescues. There are several photographs in university archives of young women beaming from top-floor windows, holding the cavernous mouth of a rickety-looking canvas tube, down which they must plummet when the flames start pulling at their stay-laces. One of the maids at LMH was so plump that she was excused the chute, for fear of getting stuck. Death rather than indignity. Bessie describes the Girton fire drill:

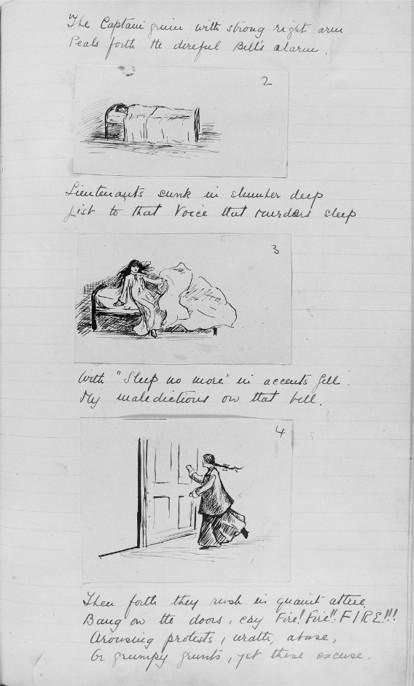

A student at Manchester University in 1905 depicts the frequent ritual of the fire drill at her hall of residence, Ashburne Hall.

Within three minutes all the corps are drawn up in their respective places. Each corps (there are three) has a captain and a sub-captain, who stand near, and overlooking all is the Head Captain. It is a bucket practice today, the one least liked by the Brigade, for there is not much incident in it, to say the least, especially in the winter when we have beans to weight the buckets instead of water… we go at a quick trot to the Middle Corridor. There we draw up in two long lines; one end joining the ‘Gyps’ Wing’, where the taps of water are. From here the buckets are handed out full – passed down to the pump at the other end (at the supposed seat of the fire) and passed back empty along the other line… At last after a weary twenty minutes of Halt! Move on! Pass buckets! – the welcome order is heard… ‘The fire is over’ is said by the H.C., and instantly everyone falls out and begins talking hard to make up for twenty minutes’ silence. Now what time is it? Five minutes to seven!…

Well now I must tackle my ‘Prometheus Vinctus’ [Aeschylus].

17

Bessie works until just after 9.00 p.m. Then it’s off to a dress rehearsal for the Drama Society play (Thackeray’s

The Rose and the Ring

) and at last, when everyone else is tucked up asleep, she returns to her room. The fire has long since died down, so it is rapidly growing cold. Breath steaming, her last task of the day is to set the alarm for next morning: 6.30 again.

How this indefatigable chronicle was meant to encourage Bessie’s family is unclear. Maybe they, like Florence Nightingale, could appreciate how gratifying it must be for an

intelligent, energetic young woman like Bessie to fill her day like this, instead of sitting in the drawing room at home, measuring life out in coffee spoons and loops of crochet.

Not everyone lived a life of such breeziness. The fabric of daily existence at college, for the first few student generations at least, was slubbed with masses of little obstacles and inconveniences. It was unnerving, for example, to be laughed at so uproariously by locals when turning up for one’s first (ever) hockey match, on a cowpat-splattered field in Durham, just because no one had told you how to hold a hockey stick and you assumed it was like a walking cane, curved end up.

18

When the first women arrived at Manchester University in the 1880s, they bravely signalled their intention to stay by installing an umbrella stand for their parasols in the original Owen’s College building. But when they asked for a common room of their own, they were allotted a small storeroom in the attics of the University Museum, which they shared with several large stuffed fish, goggling at their temerity much as the old-school academics did. When female medical students were admitted to Manchester in 1899, they were required to keep well in the background, so as not to distract the ‘real’ doctors, and to eat their lunch in an unappetizing corner of the dissecting room.

19

Most students had their meals provided for them in college or their hall of residence. Typical menus would render present-day undergraduates comatose, but the quantities and choice available were quite normal for the middle-class trencher-women of the age. At Newnham, for example, breakfast was usually porridge, eggs, ham, bacon, and smoked haddock; lunches included four or five meat or fish dishes – a roast, boiled leg of mutton, minced rabbit, giblet pie, salmon mayonnaise, stewed tongue – and sponge, milk, or fruit puddings;

for dinner there might be boiled cod, galantine of veal, curried eggs, macaroni cheese, and any amount of stewed prunes. Afternoon tea involved heaps of bread and butter (cold suet pudding being a Manchester alternative), sometimes cakes, and after dinner there would be private ‘revels’, like Bessie Macleod’s cocoa party, to which everyone brought precious biscuits or fruitcake sent from home. Sarah Mason, a former North London Collegiate pupil at Girton in the late 1870s, was outraged when Miss Buss turned up on a surprise visit one teatime and proceeded to make a great ‘hole’ in her term’s supplies.

If a young lady was forced to cook for herself, over-enthusiasm and lack of experience could result in chaos. Constance Watson of Somerville, in digs in Oxford in 1909, decided to make her own broth for visiting friends. Its ingredients were hair-raising: ‘a ham bone, a mutton bone, macaroni, buttered eggs, toast, two apples, herbs, almonds, sultanas, peas, a date, pepper, salt, milk, mushroom ketchup, and essence of lemon’. She declared it tasted ‘grand’.

20

Etiquette at mealtimes was bewildering. There were unwritten rules about who could talk to whom, in terms of seniority, and the rituals of processing into Hall, or dining at High Table, were fraught with danger – even if, as in the early days at Girton, High Table only sat two people. You had to change for dinner – nothing too gaudy – and, either on an ad hoc or rota basis, accompany the Principal into Hall every so often, and sit at her right hand making polite and erudite conversation. These occasions were completely terrifying (the Principal was often as shy as you were), and usually happened when there were undercooked peas or overcooked meringue on the menu, liable to shoot off your plate at the merest touch of a fork.

Often university would be the first place young women

mixed relatively freely with others outside their own social circle. A glimpse at the variety of entries in the space for ‘father’s occupation’ on student registration forms suggests what a melting pot colleges and halls of residence were. At King’s College, London, among those matriculating in the first few years of its existence were a shopkeeper’s daughter laden with prizes and scholarships in Classics; a hatter’s daughter from Crystal Palace (‘the best student in her year’); a builder’s labourer’s daughter who had to cope with her course being frequently ‘interrupted by home anxieties’; and an Indian girl – whose father was listed somewhat starkly as a dead doctor – struggling with work, health, and homesickness, and eventually achieving a BA in history.

21

But there were professors’ daughters there too, and those of MPs and diplomats, all studying together in what one of them called a scholarly sisterhood. In Durham, a mine-owner’s daughter might be reading for the same degree as a collier’s; lawyers’ children mixed with commercial travellers’, bishops’ with boiler-makers’, and civil engineers’ with fishmongers’.

22

In a country still stratified by social distinctions, this was a quiet revolution.

There were different age groups, too: gauche eighteen-year-olds straight from boarding school, well-read debutantes bored at home, women who worked to finance their courses (one, at Manchester, was a charlady), young widows, or – very occasionally – mothers with children at home. Pitched into the mixture were lonely, self-conscious students from Europe, America, and the British colonies around the globe, forging a strange new world in which most early women undergraduates flourished, but some inevitably failed and fled.

To all the early women students, this unprecedented way of life was a challenge. It could be coped with using common sense and open-mindedness (qualities not fostered much in

late-Victorian England), or by adopting defensive strategies. Some women shut themselves away, working eleven or twelve hours a day and emerging only to eat and take the odd stroll round the grounds or in town. There is a cautionary tale about one of these, from Leeds:

In a college, in a city, in a building large and fine,

There is many, there is many, there is many-a Clementine.

One there was among the others, like the college, very fine,

Sweet she was and very pretty, such a darling Clementine.

She delighted all Professors, and they said ‘Would she were mine!

She’s so clever, more than ever I did see a Clementine!’

She went in for Honours Classics, and her brain was like a mine,

Full of knowledge and of college, such a marvellous Clementine…

She refused to join societies or go out with friends – too busy working:

As Exam time was approaching, thinner got poor Clementine,

Then a white and pale and withered, beauty-faded Clementine.

But she still worked hard at Classics, poor demented Clementine,

And she took the examination, classic, classic Clementine.