Bluestockings (6 page)

Authors: Jane Robinson

Constance, however, was determined. Her father was the easier parent to manage, so choosing her time carefully, and wearing her prettiest smile, she asked him – ‘because learning is a beautiful thing’ – if she might go to Girton. His initial response was not promising. He laughed. ‘I say, Conse, this is something new… But what’s the

use

? What’s it for?’ Constance then embarked on a treatise about the soul-enhancing properties of Greek, philosophy, and science. Papa murmured something about staying at home and being like her sisters, before pulling out a trump card by offering to buy her a new pony if she would abandon altogether the idea of Cambridge.

At last, Constance managed to bring him round. He was prepared to allow her to leave home, he wearily agreed, and to pay her fees – but only if Mother concurred. Mother did, but on strict conditions. Constance was to be on her guard at all times at Girton: it was likely to be a ‘worldly’ place, and its inhabitants ‘not at all our sort’. She must not degrade herself by taking university exams, nor stay longer than a single year. When she returned home, she must never entertain the idea of becoming a teacher or entering some other equally wretched employment. She must treat the whole enterprise as a long visit to slightly unsuitable friends, and when it was over, do her best to forget all about it. ‘And I promised anything,’ remembered Constance, ‘everything!’

4

Why should someone like Constance have been so desperate to go to university? Florence Nightingale, like most intelligent young gentlewomen, knew the answer to that. Florence was bred to be passive in all things. She was shown

how to read, and more, but never taught to learn independently, nor explore new ideas. She was even discouraged from choosing her own books, ‘and what is it to be “read aloud to”? The most miserable exercise of the human intellect. Or rather, is it any exercise at all? It is like lying on one’s back, with one’s hands tied and having liquid poured down one’s throat.’ She was force-fed received wisdom, and it choked her. ‘Why have women passion, intellect, moral activity – these three – and a place in society where no one of the three can be exercised?’ Why are they denied the ‘brilliant, sharp radiance of intellect’, suppressed in darkness?

5

She knew how desperate a life lived in the shallows could be, and how soul-destroying it was to be condemned to triviality.

Florence Nightingale found a different way to fulfil her potential, but had a university education been available, she would have been the perfect candidate. She became one of the first reputable Englishwomen to enjoy a career. She was a formidable statistician, a quick and sinewy thinker who deftly exposed the sclerotic blunderings of the British military machine. She was a philosopher, too, of startling insight. A woman’s life is sketchy, she maintained. Someone needs to colour in the picture, give it depth. She had the bravery to do that herself; others, like Constance Maynard, needed help.

In fact, help was on its way. It dragged its feet, it’s true, for the first half of the nineteenth century, but by the time Nightingale discovered her own vocation in the early 1850s, the political and cultural movement that was to result in university places for women was beginning to gather pace and a sense of purpose. Her argument was just one of many urging on the juggernaut.

The reason for the initial lack of progress is obvious. For all the practical efforts of reformers like Bathsua Makin and

Catherine Macaulay, and the theoretical proposals of Wollstonecraft and Defoe, a vicious circle still swirled round the subject of educating girls. Until there were good schools in place to teach them the basics, there was no hope of girls’ academic development. That called for good teachers, but without good schools in the first place, where were they to come from?

Home tutoring was available, of course, to those whose fathers could afford it, and happened to approve of spending money informing the mind of a mere wife-to-be. Childhood was a middle-class invention of the Victorian era; before that infant girls were dressed as miniature women, and expected to behave as such – with some allowances – until they could earn money either by manual work or marrying well. It must have seemed to traditionalists an extravagant caprice to consider investing in female intellect. But some middle-class sisters did share their brothers’ tutors, and daughters could learn fast and well from amiable parents.

Constance Maynard, born in 1849, was one of them. Her early education, like that of so many of the other pioneers, was largely a matter of scavenging. Every Thursday afternoon, her mother would teach the four youngest Maynards an unconventional curriculum of ‘exactly what we liked’, which included printing, willow-plaiting, heraldry, drawing in perspective, and memorizing the Greek alphabet. Constance soon tired of this, and longed for her brother George to come home from boarding school and feed her real (if regurgitated) knowledge. One holiday, he brought her a map of the stars, and every clear night the two of them would steal outside and learn the constellations. ‘Here was a sort of outlet into Eternity… George and I were left to ourselves, and we laboured away at the starry sky till we “got it right”.’

6

Constance’s elder sisters had also been sent to school, and

Constance joined them for a couple of years, but it was her parents’ whim that in her case this was a waste of time and money. Father failed to see why he should go on paying for an expensive school, when Constance could quite easily pick up her education at second hand from the older girls. The implication that she was not worth the investment hurt Constance deeply, but she never complained. She had been too well brought up.

A hand-me-down education might have had its attractions for Mr Maynard, but to Constance it was useless. The Maynards’ money bought their daughters gentility, but very little learning. All those unimpeachable maiden ladies (often clusters of sisters) who ran nice, private schools for upper-middle-class daughters were more concerned with cultivation than education. If indeed they did that: the political activist Barbara Bodichon (Florence Nightingale’s cousin) publicized a worrying rise during the mid-nineteenth century of academies, institutions, collegiate establishments for young ladies – call them what you will – offering nothing but a place to deposit your daughter for a while. Most of them were staffed by incompetent opportunists, charlatans, who had failed in other walks of life and fancied opening a school to make some money. Teaching hardly featured.

Bodichon herself was lucky: she was sent to a progressive Unitarian school in London which was co-educational (something Mary Wollstonecraft advocated in her

Vindication of the Rights of Woman

) and which welcomed a mix of children from different social backgrounds. But then Barbara was from an unconventional and slightly outrageous family. Her father, a Radical MP (in his forties when she was born), never married her mother (a milliner’s apprentice in her teens), and Barbara was brought up to question received wisdom wherever it might rear its lazy head.

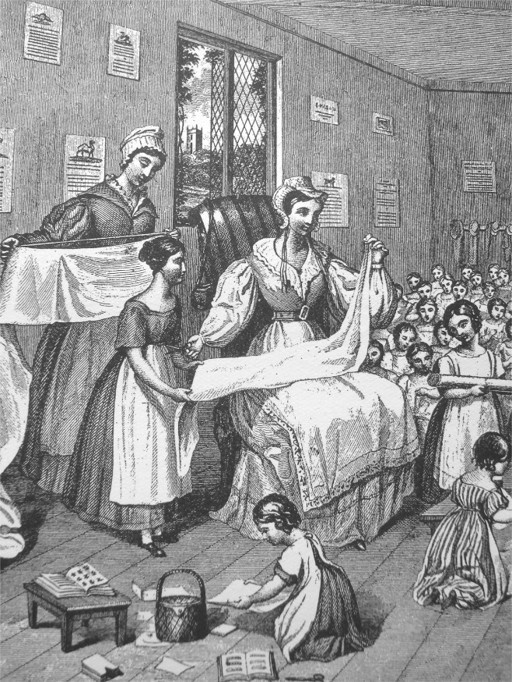

In an illustration from

The Workwoman’s Guide, by a Lady

(1840), a teacher and her assistant preside over a girls’ schoolroom. Books lie discarded while the pupils sit and sew.

Alternative schools included those run by the Quakers, or Anglican charities such as the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, the Home and Colonial Infant School

Society, or the National Society for the Promotion of Education for the Poor, which sprang up in parishes all over the country. Many of these new charity and government-aided schools were designed for the children of men and women working in the engine-room of the Industrial Revolution, yet even then only a fraction of ‘the poor’ sent their girls. It is estimated that during the 1830s three in ten children between the ages of six and fourteen went solely to Sunday school; two in ten went to a dame or a private school; one went to a National Society or parish school; and the remaining four went nowhere.

7

The sexes are not differentiated in these statistics, but it is safe to assume the minority was female.

In 1823, Casterton School was founded in west Yorkshire by the Church of England, expressly for daughters of the clergy. It was there – when it was Cowan Bridge School, the dismal pattern for Lowood in

Jane Eyre

– that the Brontë sisters went, and where their friends became pupil-teachers, ploughed back into stony ground before they had a chance to flourish in the world.

Being a pupil-teacher could be a haphazard, frustrating affair. Ellen Weeton, not so far from the Brontës, over the Yorkshire/Lancashire border, hated the position when forced into it by her indigent widowed mother in Wigan. Mrs Weeton ran her own school, and at first Ellen had been allowed to learn along with the paying pupils, soon outstripping them all. When her mother realized how precocious Ellen was, she panicked. What use to herself or anyone else was a strikingly clever girl? Rather than encouraging Ellen’s fast-developing intellect, Mrs Weeton prohibited her from lessons, except to teach the basics to fellow pupils:

Oh! how I have burned to learn Latin, French, the Arts, the Sciences, anything rather than the dog-trot way of sewing, teaching, writing copies, and washing dishes every day. Of my Arithmetic I was very fond, and advanced rapidly. Mensuration [or how to measure things] was quite delightful, [and] Fractions, Decimals, & Book keeping. So would Geography and Grammar have been, but… I could not get on as my mother would not help me.

8

Like so many in her position, Ellen was being exploited, and her eager mind trained more to shrink than to stretch.

There was a formal pupil-teacher system in place in well-regulated schools, which offered the only (vaguely) official training for women teachers in England. Grants were available to cover the apprentice’s costs from the age of fourteen until she graduated at eighteen into teaching full time. But with more schools opening, even though compulsory education was not introduced until 1870, demand for teachers was in danger of exceeding supply. The National Society decided to keep that supply ‘in house’ by opening a London training college, Whitelands, in 1841. Its aim was ‘to produce a superior class of parochial schoolmistresses’;

their

aim was to teach their girls to be good, ‘and let who will be clever’. Another five teacher-training colleges for women appeared over the next four years, and by 1850, of 1,500 women teachers working in England, 500 were professionally trained.

9

To an extent, anyway: the curriculum was neither rigorous nor challenging, but it was a start. Indeed, Whitelands was the first establishment to come anywhere close to Astell’s and Defoe’s visions of the future. The colleges were not residential (at first), nor highfalutin in their academic expectations, but they took women, young and not so young, and educated them for a career, just as Nightingale’s school for nurses did later on. The next step, of course, was to offer women

non

-vocational higher education.

*

Not all those registering for training at college were straight from school. Many were governesses, with several years’ experience behind them, but not much expertise: a little like Ellen Weeton. Constance Maynard had governesses from time to time (in fact her family seems to have run the gamut of educational opportunities). Their lessons were dreadful. Constance was expected to read aloud page after page of the dullest of history books (but never to take notes); endlessly to repeat French verbs without necessarily knowing what they meant; learn useless facts such as ‘which of our four British Queens have given the greatest proofs of courage and intrepidity’, or what tapioca was, and why the thunder did not precede the lightning. ‘I do not think I remember a spark of real interest being elicited… Of all the arithmetic I learned, and there was a little every day for several years, I can call to mind only one single rule, and it ran thus: “Turn the fraction upside down, and proceed as before.”’

10

One of Constance’s fellow students at Cambridge in the early 1870s, Mary Paley, had the same experience. All she could remember of her governess’s teaching was the date at which black silk stockings were first worn in England, and (following a theme, here) ‘What to do in a thunderstorm at night’. The pragmatic answer was to ‘draw your bed into the middle of the room, commend your soul to Almighty God and go to sleep’.

11

There is no doubt both Constance and Mary were taught by their governesses to draw, sing, probably dance, and to make polite conversation. There was even a lugubrious textbook available for the latter, with common examples of mistakes – one should not, for example, say ‘I have lost my doll’s pretty bonnet that I took so much trouble to make, and I am quite miserable about it. I told the nurse she must find it for me,’ but ‘I have met with a heavy loss. The doll’s bonnet

you saw me making the other day: mama said it was pretty; and I am grieved lest she should be angry with me for not taking better care of my things. I have intreated [sic] nurse to assist me in seeking it.’

12

This was the tinselly stuff of a governess’s education. Expectations were so low.