Bluestockings (3 page)

Authors: Jane Robinson

Newnham College was less than thirty years old when Alison arrived at the close of the nineteenth century. By that time, some 15 per cent of undergraduates in England were women. The proportion had grown to about 22 per cent by 1939.

2

Seventy years earlier, when the first women’s college was founded, the total of female university students in the country was a lonely five. Then, a female was politically classed with infants, idiots, and lunatics, as ‘naturally incapacitated… and therefore… so much under the influence of others that [she] cannot have a will of her own’.

3

That is why there were such strict regulations governing her behaviour at university (and beyond), not only to protect her moral and physical welfare, but to defend good men, such as undergraduates and lecturers, from temptation and involuntary folly.

No more was asked of a virtuous Victorian daughter than domestic duty. In its first issue, on 3 March 1880, the popular

Girl’s Own Paper

urged its middle-class readership: ‘amiable ever, but weak-minded never, brave in your duty be, rather than clever’. Intellectually, a young lady was close to nonexistent. Her brain was considered small and dilute compared with a man’s, and her understanding generically shallow. Her constitution was not thought to have the physical, mental, or emotional resources to withstand reproduction

and

academic

study. A fertile womb and a barren brain, or vice versa: the choice,

pro bono

, was clear.

Therefore, for the first few decades of their admission to university, women were treated with little more confidence than those infants and idiots. When Manchester allowed female undergraduates in the 1880s, it put them in a small room in the attic, sternly guarded by a stuffed gorilla and some moth-eaten lions and tigers from the university museum. Chaperones were required for social and academic occasions, everywhere, until the First World War. Lecturers could refuse to teach or even acknowledge women. For a long time no males – including fathers and brothers – were allowed in women’s rooms; after dispensation was granted to family members and (at a push) fiancés, it was still the rule that the bed should first be removed from the room, and the door propped open.

You might argue the situation was not much better by 1939, the end of the period covered by this book: Cambridge refused to award women degrees before 1948, and it was not until 1959 that the women’s ‘halls’ at Oxford became fully incorporated into the university. Less than a quarter of the country’s undergraduates were women, and when they graduated, they were still encouraged to choose between a profession and marriage.

To focus on these negatives, however, would be unfair. Nothing should distract us from the achievements of ordinary, extraordinary women like Alison Hingston, on whom this book is based. Quietly (or occasionally with some hullabaloo) they cleared the path that hundreds of thousands of women have since followed; most of us without a backward glance.

A word or two about terminology: an undergraduate is taken to be a student at any university, even though women were not allowed officially to graduate from Oxbridge until

comparatively late, and were therefore not strictly

under

graduates at all. I know Dorothy L. Sayers was not alone in abhorring the term ‘undergraduette’, finding it intolerably patronizing. But in the context of its era (principally the 1920s) it was also used with affection and even pride, both by students themselves, and by their observers. Bluestockings with a capital ‘B’ are those luminous intellectuals who graced the literary and artistic salons of fashionable eighteenth-century society; stripped of the pejorative gloss the label has acquired since then, it is here reclaimed – with a small ‘b’ – for all the undergraduates who give this book its voice.

4

1. Ingenious and Learned Ladies

A Learned Woman is thought to be a Comet, that bodes Mischief, when ever it appears. To offer to the World the Liberal Education of Women is to deface the Image of God in Man, it will make Women so high, and men so low, like Fire in the House-top, it will set the whole world in a Flame…

1

Life had not been kind to Mrs Pearson. She grew up around the turn of the twentieth century, when the second generation of women students was enjoying a university education. She might have gone to college herself, but brains and ambition in those days were not enough. She lacked the necessary background and money. Now, in the early 1930s, she found herself impoverished, living in a tiny house in south London, with an unemployed husband in his seventies, their children, and no reliable income. Keeping the family together, fed, and sheltered during the Depression was a struggle to which Mrs Pearson, in her darker moments, felt unequal.

One person kept her going: a daughter, Beatrice, in whom she recognized her younger self. Beatrice – known to everyone as Trixie – was indomitably cheerful. She was also extraordinarily bright. Somehow, Mrs Pearson managed to keep Trixie at school beyond the minimum leaving age of fourteen (even though she could have been earning a wage and off her mother’s hands), and when the girl was encouraged to apply for a scholarship to university in 1932, the whole family was overjoyed. A teacher suggested St Hilda’s

College, Oxford. It would have been far cheaper to send Trixie to one of the women’s colleges in London; then she could have lived at home, and walked to her lectures each day. But if she was good enough to try for Oxford, declared Mrs Pearson, then Oxford it must be.

Everyone rallied round. As soon as the incredible news came through that Trixie had been accepted by St Hilda’s, work parties sprang into action to create what her mother proudly called her Oxford trousseau. Convinced (wrongly) that all Trixie’s peers would have their family crests lavishly embroidered on silken underclothes, and engraved on silver knives and forks and napkin rings, an aunt doggedly stitched Trixie’s initials on her clothes and linen, as the next best thing. Fashion magazines were borrowed and scoured, material cadged and bartered for, with the mortifying result that Trixie attended her first ‘cocoa party’ at college clad not in homely winceyette, like everyone else, but in a gloriously sophisticated one-piece ‘lounging pyjama’ in glancing black satin, straight from the pages of

Vogue

.

One of the most difficult things for Trixie to get used to at St Hilda’s was the silence. On the banks of the River Cherwell, opposite Christchurch Meadows, it was surreally still at night. She had never before had a room of her own, privacy, carpets, so many books at her disposal, and all the food and heat she needed. There was butter at teatime,

and

jam. She felt guilty. They could afford only a scrape of putty-coloured margarine at home. Never mind, she told herself; her being at Oxford would mean butter for them all in the end.

While Trixie was away, the Pearson family slumped even deeper into poverty. The obvious economy was for Trixie to leave Oxford and find a job. But Mrs Pearson was adamant that her daughter should not even be told about their difficulties and, despite ill-health, went for an interview for a

full-time job as a charwoman. She failed to get it: she could hardly bend.

Soon the financial situation became so desperate at home that Trixie had to know. She was distraught, and promptly lined up a post as a bank clerk at £2 per week. Her mother was furious: it was madness for Trixie to mortgage her university career and the whole family’s future for little more than £100 a year. As an Oxford graduate, teaching, she would earn more than twice that, and have a pension. She would be able to climb out of all this, insisted Mrs Pearson, and the family would climb out too, on her coat-tails.

So Trixie stayed at Oxford. The Pearsons went on to poor relief, and discreetly, with infinite sensitivity, the college invented grants and bursaries to help, some of which – Trixie discovered later – came straight from the pockets of her tutors.

Trixie adored university life, and was one of the most popular, shining girls of her college generation. Occasionally, members of her family would come to visit. They had to take turns, once enough money had been scrimped for someone’s train fare, and none of them seem to have resented her being there. Mrs Pearson hardly ever came, so that others could, but when Trixie graduated, she insisted her mother be present. The Dean of St Hilda’s spotted Mrs Pearson in the Sheldonian Theatre, where the ceremony took place, quietly making for the high balcony with the parents of other students. They were supposed to sit well away from the ranks of academic dignitaries below, but the Dean fished Mrs Pearson out, leading her down to the reserved VIP seats right at the front. ‘This ceremony means more to Mrs Pearson,’ explained the Dean, ‘than to anyone else here today. Of

course

she must have a good view.’ Trixie, waiting behind the scenes, knew nothing of all this until she

emerged to receive her degree. Then came the proudest moment of her life:

As Bachelors we naturally came last, of interest only to ourselves and our families. When the Proctor called upon our Dean to read out her candidates’ names and present us, we had to go forward and stand in a group around her. In that position we were face to face with and only two or three yards from the Vice-Chancellor, the Proctors – and my mother.

2

I wish those who fought so hard for the right of women to attend university and be awarded degrees could have known about Trixie Pearson. Everything about her story vindicates what they were trying to do. Despite her social background, her academic abilities were recognized and nurtured; she was encouraged to aim for the best, and supported financially, emotionally, and academically to do so; doors opened for her as she approached, and nothing was allowed to stand in the way of her undergraduate career, until she stepped confidently out into the working world as a professional woman. The family

did

climb out of poverty on her coat-tails, just as Mrs Pearson promised, and through her own teaching Trixie passed on the excitement of learning and the concept – very new to young women at the time – that nothing is impossible.

Trixie graduated in 1936, nearly sixty years after the first degree courses were opened to women at an English university. The image of the ‘bluestocking’ had been a familiar concept throughout those years. It still is, to a certain extent. I remember being thrilled when my English teacher called me a bluestocking the day I won my place at Oxford. Like Trixie, I was not expected to get in, since no girls from my school had been before, and the college to which I had blithely

applied was renowned for its clever women. I naturally assumed blue stockings were part of their uniform and that on special academic occasions, with gown, cap, and a sober suit, I should wear them too. One of the first things I did on hearing the news was visit Mr Beckwith, the local draper, to buy a couple of pairs of navy tights (a daring take on tradition). Someone put me right before I embarrassed myself too much, but achieving bluestocking status remained a slightly exotic badge of intellectual honour in my imagination.

The very first bluestocking was not a woman at all, but the naturalist and writer Benjamin Stillingfleet (1702–71). He belonged to a group of fashionably learned friends who met together during the latter half of the eighteenth century in various London salons to cultivate the art of intellectual conversation. The novelty of Stillingfleet’s group was that most of its members were female. Elizabeth Montagu (1720–1800), its ‘Queen’, was a wealthy woman passionately interested in English literature; a patron and an author, she counted the celebrities of the day – writer Samuel Johnson, actor David Garrick, painter Joshua Reynolds – as fellow scholars as well as friends. At first they humoured her because of her income of £10,000 a year, one suspects; later, however, they appear genuinely to have admired her critical flair. Partly thanks to her, being an overtly intelligent woman acquired (fleetingly) the gloss of high culture and became fashionable.

One evening in 1756, Stillingfleet presented himself at Elizabeth Montagu’s Mayfair house for one of the company’s regular meetings, bizarrely clad not in customary white silken hose, but in workaday knitted blue stockings. Woad-blue wool was cheap and common; Mrs Montagu and her friends thought it hilarious that Stillingfleet was eccentric enough not only to have countenanced possessing such stuff in the first place, but wearing it in public.

Stillingfleet’s solecism was gossiped about throughout literary London, and soon Mrs Montagu’s clique became known collectively as the ‘blue stocking philosophers’. Especially the women. Her house was dubbed ‘Blue Stocking Lodge’ or ‘the Colledge’ and considered an urbane sort of private university over which she and her scholarly lady friends presided as unofficial Doctors of Letters.

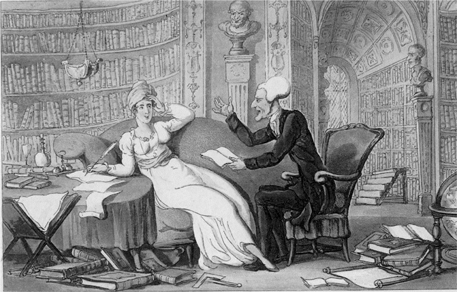

Dr Syntax woos a ‘Blue Stocking Beauty’ in one of Thomas Rowlandson’s cartoons illustrating a popular satirical poem,

The Third Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of a Wife

, by William Combe (1821).