Bluestockings (24 page)

Authors: Jane Robinson

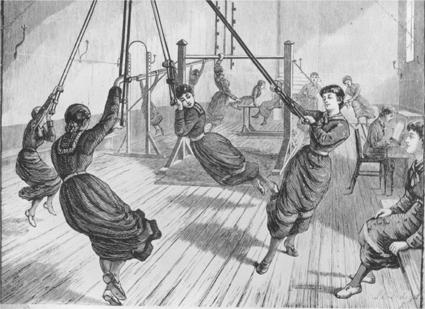

Pupils at Miss Buss’s North London Collegiate School practise in the gymnasium in 1882, with unlikely poise and finesse.

Once a competitive edge was introduced, especially in team games, women’s sport became less about serious duty and more about serious fun. Teams bought themselves smart blazers and college ties; they posed for endless photographs and trained for hours; every victory was celebrated, every defeat resented, and a new breed of college heroine was born.

The river featured heavily in the sporting life of London, Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham universities. Rowing was preferred to the ungainly art of punting, and safety was paramount. Kathleen Proud was a student at Royal Holloway

during the First World War, and remembered strict college regulations:

A swimming test had to be passed, including life saving and three lengths of the bath in clothes. Each rowing party consisted of 5 people: a Beginner, a Moderate, two Efficients and a Captain. One had to pass a test to get from one stage to the next, and the Captains were tested by a few very superior Captains who became Judges.

7

Usually, a doctor’s certificate of good health was also required. Sadly, these rules were not enough to prevent occasional disaster. There was a near-tragedy in Durham one morning in March 1922 when the St Mary’s College boat,

Iris

, was taken out by some inexperienced students. They started before breakfast, ‘because it was a very broad boat for amateur women and likely to be jeered at by the men’. The river was choppy and confused, and despite the women’s best efforts,

Iris

was swept over a weir and capsized. News reached college quickly, but imperfectly; the rumour was that all the rowers had been drowned. Happily, that was not so. Instead, the boat grounded on a shelf by a second weir, and its crew was dramatically rescued. To celebrate their deliverance from certain death, the Archdeacon of Durham (who had presented the college with

Iris

in the first place) arranged a thanksgiving evening, at which each of the survivors was presented with a silver St Cuthbert’s Cross. One of the recipients remembered feeling rather embarrassed: the archdeacon’s daughter was her tutor, ‘who must privately have thought us perfect idiots to have gone boating in a strong wind, on a river already high’.

8

The Cherwell, Isis, and Cam are customarily more languid than the Wear, and nothing much worse than seasickness while punting, or accidentally subsiding into the water, seems

to have beset the boatwomen of Oxford and Cambridge. They were advised to clamp their skirts around their legs with elastic bands while rowing on movable seats, to preserve their modesty from passers-by on the bank, and – in time – to wear bloomers. Racing was forbidden on the river until the late 1920s, much to the chagrin of the Somerville Rowing Club, as expressed in the following song from 1922:

ON REFUSAL OF PERMISSION FOR BUMPING RACE WITH THE REASONS THEREOF

(Tune: ‘O Foolish Fay’,

Iolanthe

)

Your strange request

We must refuse

When you suggest

With rival crews

Here to contest

Your strength of thews.

To show your face

In feats of skill

In public place

Most surely will

Bring dire disgrace

On Somerville…

The brawny arm

Is merely plain;

And with alarm

We view the strain…

And beg that you

Will keep in view

The future generation.

9

Individual pursuits suited certain characters better than team sports. Mountaineering was surprisingly popular. One student at Royal Holloway was skilled enough to be involved in the Ladies’ Alpine Club in 1930. At Birmingham, ladies climbed closer to home. ‘Joe’s Folly’, a tall brick edifice on the campus in Edgbaston (named for the university’s leading light, Sir Joseph Chamberlain), proved irresistible. The daughter of students there in 1926 has photos ‘of virtually every male member of my mother’s “lot” and a surprising number of women too, hanging perilously from the fancy brickwork at the top of the tower. Absolutely forbidden by the authorities, of course, and with no safety measures whatsoever!’

10

Royal Holloway and Girton colleges were both built with swimming pools, which sounds sophisticated, until we hear that the water in the latter place regularly grew ‘green and soupy’ before it was cleaned (although it did have a compensatory inflatable rubber horse).

For those who could not swim, and were neither competitive nor adventurous, there was always cycling. ‘The most useful thing I learned at Oxford,’ declared a satisfied student of St Hugh’s, ‘was to ride a bicycle in all circumstances.’ Colleges had bicycle clubs to encourage weekend expeditions. Some even provided the cycles, but funds did not allow more than one or two, which frustrated most of the members most of the time. Women thought nothing of pedalling long distances. The Fredericks sisters, Grace, Julie, and Daphne, were scattered between Oxford and Cambridge universities in the late 1920s; when Julie (Newnham) wanted to visit Grace (St Anne’s), she simply climbed on her bike and rode across England.

Tricycles were recommended for beginners at the end of the nineteenth century, and there was naturally a dress code:

Wear as few petticoats as possible; dark woollen stockings in winter, and cotton in summer; shoes, never boots; and have your gown made neatly and plainly of C.T.C. [Cyclists’ Touring Club] flannel (not the cloth, which is too thick and heavy for a lady’s wear), without ends of loose drapery to catch in your machine…

If stays are worn at all, they should be short riding ones; but tight lacing and tricycle riding are deadly foes. Collars and cuffs are the neatest wear to those happy women to whom they are becoming. All flowers, bright ribbons, feathers, etc., are in the worst possible taste, and should be entirely avoided.

11

If even cycling were beyond a student (perhaps she could not afford the equipment), the final resort was walking. College grounds might be extensive enough for reasonable exercise; Girton’s took a good half-hour to stroll around, and eleven tedious circuits of the tennis court at Newnham equalled a mile. Sunday afternoon rambles to neighbouring village churches, or through the more picturesque quarters of the city, were routine. Gathering moss and fresh daffodils and kingcups to decorate your room, or sketching architectural curiosities, gave the walk a sense of purpose; at the end of it, there was usually a just reward in copious amounts of tea and cake.

Although sports clubs accounted for a good proportion of the Junior Common Room’s activities (the JCR being the undergraduate body of a college or hall of residence), there were other things going on. The common room itself was the focal point of student relaxation, and was decorated with whatever resources were available. Each common room had comfy (if elderly) armchairs or settees, usually a donated piano, dubiously tuned, and in due course a gramophone with a small library of records. The minute books of JCR

committee meetings reveal what each establishment prioritized. At Manchester, Ashburne Hall’s taste in pictures was conservative: the students spent their £3 picture allowance in 1902 on reproductions of Constable’s

The Hay-wain

, Millais’

The Gleaners

, and Watts’

Love Triumphant

. They cancelled their subscription to the

Daily Telegraph

that year because no one ever read it, but the satirical magazine

Punch

was so popular that back numbers were auctioned at the end of each month. By 1938, two copies of the socialist

Daily Worker

were provided; there was a cigarette machine (smoking had been allowed since 1919), and a Horlicks dispenser in the basement. Still no alcohol, however.

12

Leeds women’s JCR was truly progressive. It acquired a telephone and a Nestlé’s chocolate machine in the mid-1920s, and by 1930 a communal camp bed ‘for use of any student requiring to lie down’, complete with hot-water bottle and blanket. It set aside a ‘small garret’ for the private relaxation of members who were nuns, and included – for some reason – the

Indian State Railway Magazine

among an eclectic array of periodicals.

13

Debating societies were ubiquitous. In enlightened universities, male and female undergraduates met together, and provocative motions stimulated some lively evenings’ entertainment. ‘This House believes that it is better to remain single’, for example, or ‘Accomplished women give more pleasure to others than strong-minded ones’, or ‘Pedestrians should carry rear lights’. A proposal ‘that the Parliamentary Franchise should be extended to Women’ was moved at Manchester in 1898. One speaker pointed out that women were patently unfitted for political life, and only the ‘lowest classes’ would vote once the novelty had worn off. The motion was defeated.

14

Eight years later, in Birmingham, the subject came up again. Now the opposing argument was

that ‘the excitement of voting would be detrimental to women’s health’; this was parried by the ladies’ Warden, Margery Fry (later Principal of Somerville), who ‘failed to see why the [electoral] line should be drawn at “women, paupers, and lunatics”’. She thought her sex might just be capable ‘of taking a walk to the polling booth’ and surviving. This time the motion was carried – but only with the female president’s casting vote.

15

Not all debates were as sparky as Manchester’s and Birmingham’s. At University College, London, they had become so tedious by 1928 that guidelines were published in an effort to pep them up. Speakers were encouraged to make notes and strike points off their own list as they were made by others; to improve vocabulary and forgo slang; to avoid starting each sentence with ‘I think’; and to ‘take care of vowel sounds’.

Drama clubs flourished everywhere. Regulations against women wearing trousers meant an early preponderance of Greek plays, where male characters fortunately wore togas, and were efficiently differentiated from women by the attachment of impressive but anachronistic waxed moustaches. Freshers were expected to perform plays and charades to the whole college, and the ‘going-down’ play, usually some sort of mildly satirical revue staged by finalists, was an occasion not to be missed. Women were not encouraged, and at Oxford not allowed, to perform on the same stage as men until the 1920s, but this does not appear to have dulled the dramatic appetite. How much their performances would appeal to modern audiences is unclear. An evening of ladies’ intercollegiate charades at Oxford in the 1920s sounds less than enthralling. Each of the college teams was supplied with one syllable of a charade. The word they had to guess was ‘radiography’. Somerville did a piece from a medieval

problem play with a princess, knights, and dragons; St Hilda’s did a prehistoric trial scene; St Hugh’s set the action in a French customs office; and Lady Margaret Hall did an extract from a play called

The Boys of St Winifred’s

. ‘There was only one Home Student there, so she did a sketch about hop-pickers, and the committee did the whole word.’ I wonder how many guessed the answer – or cared.

In addition to all the college activities, each university faculty tended to run its own society. Modern languages clubs involved conversation and literary discussion; English scholars arranged reading weeks in the country; politics and philosophy students elected pretend parliaments and passed mock laws; geographers indulged in informal weekend field trips. These subject-related activities had mixed membership soon after women students arrived. Joining them presented welcome opportunities to meet students of the opposite sex on neutral, relatively non-judgemental territory. Subscriptions were expensive, but with careful economy most students could afford one or two. Biologist Marjorie Collet-Brown had nothing left over once she had paid her subs, so when an expedition to Mount Snowdon was proposed, she defied the order to purchase proper climbing breeches by sewing her own from an old pair of black velvet curtains. They were much admired.

Those who arrived at university with musical skill were soon swept up by choirs and ensembles of variable expertise. In Oxford the premier choral society was the Bach Choir. Angst-ridden weekly rehearsals (at the Pitt Rivers Museum, as we saw in the previous chapter) led to triumphant termly concerts. Dorothy L. Sayers and Vera Brittain were both Bach Choristers, and were captivated by its charismatic director, Sir Hugh Allen – especially Dorothy who, according to Vera, constantly gazed at him ‘as though she were in

church worshipping her only God’. For those with more modest musical ambitions, every college and hall of residence boasted a repertoire of college songs, which students were expected to learn and perform with gusto. When finals results proved unexpectedly impressive, to celebrate a sporting triumph, or on a host of lesser occasions, new words to old tunes were proudly belted out, and every so often volumes appeared, printed or handwritten, like jolly college hymnals. There was always an official anthem, rather pompous and probably in Latin; supplementary songs were composed as different cohorts of bluestockings came and went, either witty or intense. I have come across a ‘Bicycle Secretary’s Song’, a ‘Fire-Engine Song’, songs to celebrate working hard or being lazy. Most common are the songs that urge women to scale the academic heights, thus joining or displacing those men already there. Girton has the best, written in 1887. Its chorus gets straight to the point: