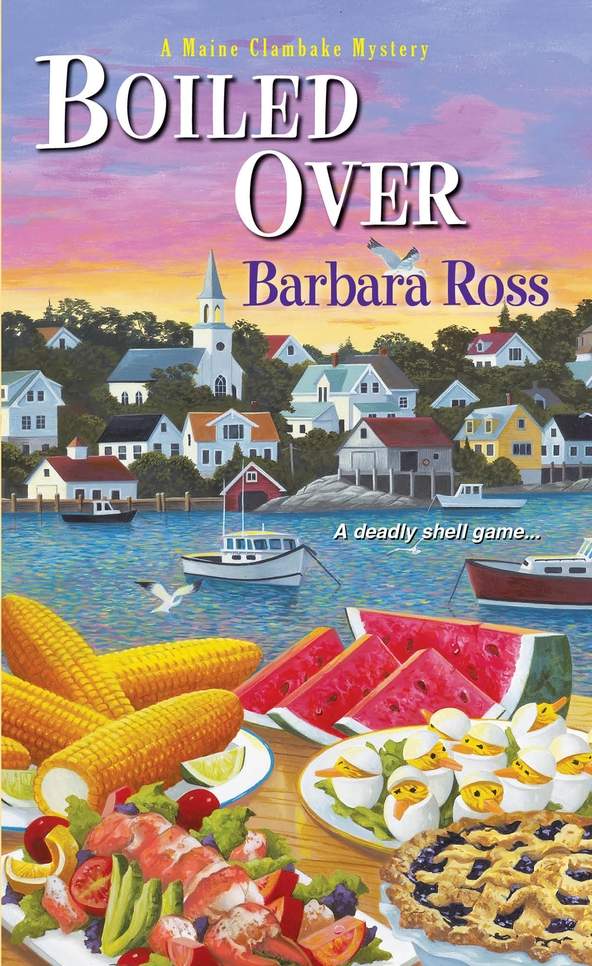

Boiled Over (A Maine Clambake Mystery)

Read Boiled Over (A Maine Clambake Mystery) Online

Authors: Barbara Ross

At the Claminator, Sonny conferred with Cabe, his expression serious. As the band hammered its way to a big finish with the “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” Bunnie climbed the single step to the stage and stood behind the podium. I scanned the crowd for Stevie, but didn’t see him. Evidently, Bunnie was done waiting.

From my perch on the curb, I glanced over at the Claminator. Sonny and Cabe’s conversation grew more intense. Even from thirty feet away, I could tell Sonny was unhappy about the fire. Livvie scooted over to speak to him, then walked away, looking concerned. Sonny lifted the mesh skirting of the Claminator and aimed the hose he’d been using to spray the canvas at the fire to dampen it. He jumped back as the flames surged outward, like a grease fire. But there was no grease in a clambake meal that could drip into the fire. I’d worked at the clambake for years and had never seen anything like it. But then we’d never cooked on the pier before. This was the maiden voyage of the Claminator.

Sonny said something urgently to Cabe, who jogged toward the fire truck parked on the street beside the pier. Sonny bent down and lifted the metal skirting again, a poker in hand. The crowd surged around him, blocking my view. Sonny swore loudly.

I shoved forward. “Please! Let me through!”

The crowd parted just in time for me to see something that looked like a charred human foot fall out of the fire onto the pier . . .

CLAMMED UP

BOILED OVER

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

Barbara Ross

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Books by Barbara Ross

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Recipes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Copyright Page

This book is dedicated to my son Robert Carito,

the funny, caring, searingly honest old soul who,

as my first-born, taught me more than anyone

about what it means to love.

“Excuse me! Sorry. Coming through.”

I elbowed my way through the crowd on the town pier, barely taking in the sights, sounds, and smells of Founder’s Weekend in Busman’s Harbor. Mother Nature had smiled on us, providing a sunny, dry morning fanned by a comforting sea breeze—the kind of weather that convinced tourists there was nowhere better to spend an August Saturday than on the coast of Maine.

“Coming through.” My dual roles as a member of the Founder’s Weekend committee and manager of the Snowden Family Clambake had conflicted. I was late.

In a semicircle around the pier, four food vendors prepared for the lunch rush, set to commence immediately after the opening ceremonies. In the Snowden Family Clambake area, my sister Livvie stirred a vat of her amazing clam chowder. Her husband Sonny and Cabe Stone, his young helper, sprayed saltwater onto the untreated canvas draped over the seaweed covering the lobsters, clams, corn, potatoes, onions, and eggs we would soon serve to the first three hundred people who came through our buffet line.

Normally, we ran our clambakes on Morrow Island, the private island my mother owned two miles southeast along the coast. On the island, we cooked everything in a big hole in the ground on rocks heated by a hardwood fire. When I’d first proposed to my brother-in-law that we provide food for Founder’s Weekend, he’d reacted with the same stubborn negativity with which he greeted all new ideas—particularly mine. He reddened from the base of his wide neck to the top of his red-haired, buzz-cut scalp.

But my sister Livvie had backed me up. She had to. She was the whole reason I was on the stupid Founder’s Weekend committee in the first place. So, Sonny did a one-eighty and spent hours with Cabe figuring out how to cook safely on the pier.

The result was an oddly beautiful contraption Sonny had proudly dubbed, “The Claminator.” Twenty feet long and four feet wide, it looked like a cross between an enormous steam table from a high school cafeteria and a gurney for Frankenstein’s monster. Raised edges around its table-height top held perforated metal baskets containing the mounds of food. A dense mesh curtain designed to contain the blazing wood fire underneath surrounded the lower part of the Claminator. Thank goodness the pier was concrete, or we’d have burned down the town.

A thin cloud of smoke hung over the pier and I wondered if the Claminator fire was burning too hot. But Sonny was watching it and he was the expert. The smoke must be coming from Weezer’s Barbecue located next to us. I wasn’t sure what barbecue had to do with Maine cuisine, but the sweet, smoky smell of Weezer’s sizzling pork ribs made me think traitorous thoughts about heading through his line when it came time to eat.

“The Claminator is gorgeous,” I said when I finally reached Sonny. I had to give him his due.

“Works great, too!” he shouted in the direction of Weezer’s barbecue. “At least, I’m not cooking on something that looks like a tanning bed for pig parts!”

Weezer grilled his meat on a weird rig that looked like a hot-water heater sawed in half.

“At least I’m not cooking bugs wrapped in seaweed!” Weezer shot back.

“We’ll see who gets the longer lines!”

I had a feeling they’d been going at it all morning.

The other businesses in the semicircle were the town ice cream parlor and the Busman’s Harbor bakery, which at this time of year was selling pretty much anything on earth that could be made with blueberries. The owners went quietly about their business, ignoring Sonny and Weezer.

“What a glorious morning.” Richelle Rose touched my arm to get my attention. She was a tour guide, a decade or so older than my thirty years. Tall and Amazon-glamorous, she had breathtaking, dark blue eyes and the kind of white-blond hair most people lost after childhood.

Everything seemed under control in the clambake area, so we moved away from the noise of the crowd to a spot at the edge of the pier where we could talk. I stood on the cement curb so we’d be face-to-face. “Thanks for being so flexible.”

“Glad we could work it out.” Normally, Richelle would have brought her busload of tourists out to our island, providing them with a scenic harbor cruise as well as a meal. To accommodate Founder’s Weekend, she’d agreed we could feed her clients on the pier. Though they’d miss the cruise and seeing the island, they’d get the benefit of all the Founder’s Weekend activities—the windjammer parade and lobster boat races, the art show and concert, and finally, a gigantic fireworks display—before they were loaded onto their bus and driven on to their next hotel up the coast in Camden.

“How is this group?” I asked.

She rolled her eyes. “Shopaholics.” She’d shepherded her charges through the outlet stores in Freeport before they’d even arrived in Busman’s Harbor that morning. Richelle had an expansive knowledge of all things Maine—history, geography, flora and fauna on land and at sea. Though she kept a smile on her face, I knew it drove her crazy when she had a group who only wanted to see the inside of a mall.

As we chatted, I gazed at the ring of buildings that backed onto the pier. With all the people milling around, I couldn’t see much, but I could look up. Sometimes being short gave me an interesting perspective. Up on a top floor balcony at the Lighthouse Inn, a broad-shouldered man shot photos through a lens as long as a spyglass. Another camera with a shorter, but still impressive, lens sat on a tripod next to him. Most of the balconies were occupied by folks enjoying the festivities on the pier. Well, maybe not so much

enjoying

as

recording

. Every person up there observed the pier through some sort of device—phone, camera, tablet computer—as if documenting the scene was more important than being part of it.

“Who’s that working the clambake with Sonny and Livvie?” Richelle asked.

“Cabe Stone. He’s new. I hired him at the end of June.”

“Seems like a good worker.”

“He’s terrific,” I assured her. “Don’t worry, your customers are going to be thrilled with their meals, even though we’re cooking them on that thing.” I pointed at the Claminator and Richelle laughed.

In front of the makeshift stage, our high school band began an enthusiastic, if only moderately on-key and on-tempo rendition of “You’re a Grand Old Flag.” Fee Snuggs, my seventy-four-year-old neighbor puffed out her cheeks and blew into her slide trombone. Busman’s Harbor High wasn’t big, so once you were in its marching band, you didn’t get out until you moved away or died.

Across the way, Bunnie Getts, the chair of the Founder’s Weekend committee, finished an emphatic conversation and hurried toward me. “Ten minutes, Julia!” Bunnie called over the noise. “As soon as the band stops, I’ll give a little history of the town and then I’ll introduce the committee. Make sure you’re up at the front, so we don’t have to wait for you.”

I nodded to show I understood, and she went on without taking a breath. “Have you seen Stevie? I’ve rounded up all the Founder’s Weekend committee members except him. And, Bud, of course. But I know better than to expect Bud.”

I shook my head. “I’m surprised Stevie isn’t here. He’s been excited about the opening ceremony since day one.” The ebullient owner of the local RV campground, Stevie had been a relentless booster of Founder’s Weekend for all the tedious months the committee had labored to pull this first-time event together. I started to tell Bunnie I’d look for him, but she’d already pinged off in another direction.

At the Claminator, Sonny conferred with Cabe, his expression serious. As the band hammered its way to a big finish with the “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” Bunnie climbed the single step to the stage and stood behind the podium. I scanned the crowd for Stevie, but didn’t see him. Evidently, Bunnie was done waiting.

From my perch on the curb, I glanced over at the Claminator. Sonny and Cabe’s conversation grew more intense. Even from thirty feet away, I could tell Sonny was unhappy about the fire. Livvie scooted over to speak to him, then walked away, looking concerned. Sonny lifted the mesh skirting of the Claminator and aimed the hose he’d been using to spray the canvas at the fire to dampen it. He jumped back as the flames surged outward like a grease fire. But there was no grease in a clambake meal that could drip into the fire. I’d worked at the clambake for years and had never seen anything like it. But then we’d never cooked on the pier before. This was the maiden voyage of the Claminator.

Sonny said something urgently to Cabe, who jogged toward the fire truck parked on the street beside the pier. Sonny bent down, lifted the metal skirting again with a poker in his hand, and swore loudly.

The crowd surged around him, blocking my view.

I shoved forward. “Please! Let me through!”

The crowd parted just in time for me to see something that looked like a charred human foot and part of a leg fall out of the fire onto the pier.

Sonny jumped back. A woman screamed. I reached his side, “Oh my God, Sonny. Is that—?”

He grabbed my hand and we advanced toward the thing. I looked away. I couldn’t stare directly at it. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted Cabe running, in long, loping strides, not toward us, or toward the fire engine, but off the pier and up the steep street.

As Sonny used his poker to confirm what my mind was denying, there was another terrified scream, this time from behind us. I whirled around. The crowd parted again. Richelle Rose lay on the ground, her head resting awkwardly on the cement curb where we’d just stood.