Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (42 page)

A cartoon by R. Hoyt, one of many artists following Nast’s example in satirizing the Tweed Ring.

It was a remarkable fall. Six months earlier, William Magear Tweed, the Boss of Tammany, had stood at his height, the Monarch of Manhattan, lavished with diamonds, praise, and statues. Now, he’d been reduced to a criminal and a laughing stock, shunned by friends, un-pitied, and losing his fortune. Even poor workmen on the street without a dime turned their backs on him. “What the divil’s the use o’ stickin’ to ‘m, whin there’s nothin’ to stick to,” one Irish street laborer was heard saying.

41

In the cruel, arbitrary world of 1870s America, Tweed had become a marked man, literally a cartoon character—villain and chief swindler, presumed guilty, beyond fairness. There was no place left for him in respectable society.

• PART IV •

FALL

“STONE WALLS DO NOT A PRISON MAKE.”

—Old Song.

“No Prison is big enough to hold the Boss.”

In on one side, and out at the other.

Harper’s Weekly, December 18, 1875.

CHAPTER 18

LAW

“ It is a great, a splendid and a noble victory, Sir…. Tweed and his gang are doomed. This is only the commencement, and before many days pass it will be made so hot for the arch robber that New-York will not hold him…. We will now see what can be done to have refunded the enormous amounts stolen from the City and County Treasury.”

—

SAMUEL J. TILDEN

, on the election victory of the Apollo Hall reformers over Tammany, November 7, 1871.

1

“ I have got twenty more years of life to live yet. I’m only fifty years of age. Time works wonders, they say, and it will work a change in this. I guess I shall live it all down.”

—

TWEED

, after his first criminal trial, January 31, 1873.

2

G

ENTLEMEN, have you agreed to your verdict,” Judge Noah Davis asked the twelve men sitting in the jury box of the crowded court of Oyer and Terminer—the criminal trial branch of New York’s Supreme Court —on Friday morning, January 31, 1873.

3

The foreman rose to his feet. “No, sir.”

The trial had lasted seventeen days, heard dozens of witnesses, and consumed hours in legal arguments. The jury had been deliberating since the prior afternoon, locked up over night, and taken over forty fruitless ballots. Tweed had come early each day to the Courthouse on Chambers Street though the coldest part of winter; snow clogged the sidewalks and the thermometer at Hudnut’s Pharmacy in the

New York Herald

building had dropped to a bone-chilling three degrees the night before. Wearing a dark suit and white tie, he sat surrounded by family, his sons Richard and William Jr. and older brother Richard, and lawyers enough to fill a small jail.

Now, the judge and jurors glared at each other. “Gentlemen, is it likely that, with any little longer time for consideration, you can agree?” Judge Davis looked more sad than angry in his crisp black tie and black robes.

“I think not,” the foreman said. After a few minutes, he sheepishly sat down.

“Is there any other juror who wished to state anything on the subject?” Juror five stood up and explained that they’d all agreed at 7 am that morning to give up. “I suppose you have exerted the efforts to agree, and I do not see that any benefit can result from keeping you out longer,” Davis sighed. “Then you are discharged, gentleman.”

A hung jury. Tweed was free, at least for now. He showed little emotion in the courtroom. It had taken a full year since his fall from power for prosecutors to bring him to trial. Grand juries had filed eight separate indictments against Tweed in New York’s Court of General Sessions on charges from forgery to corruption to abuse of power to neglect of duty—felonies, misdemeanors, big and small. The whole Tammany gang—Tweed, Sweeny, Connolly, Hall, Garvey, Woodward, Ingersoll, Sweeny’s brother James—all stood charged in the scandal, including five indictments against the mayor alone. Tweed’s total bail topped $1.5 million.

But he’d beaten the rap.

For Tweed’s trial, State Attorney General Francis Barlow had stacked the deck by bringing in two high-priced outside lawyers to argue the prosecution case: Wheeler H. Peckham, forty years old, thin, mustached, son of a sitting New York appeals court judge in Albany and brother of future Supreme Court Justice Rufus W. Peckham, had practiced law in New York City since 1864 and been counsel to the Committee of Seventy. Backing him up was Lyman Tremain, a former district attorney, state attorney general, and speaker of the state assembly. To win a quick conviction, they’d chosen to prosecute Tweed on the easiest charges to prove: the so-called “big” or “omnibus” indictment, a package of 220 counts—“More counts than in a German principality,” the judge himself had quipped.

4

The charges stemmed primarily from the 1870 Tax Levy, by now the most heavily audited transaction in history, and centered on two basic violations: that Tweed had neglected his legal duty to “audit” claims for payment from the county (three statutory counts) and that Tweed had been corrupt by abusing his public position (one count). These four counts were then applied to each of fifty-four specific incidents: individual payouts under the Tax Levy package.

Since each violation was only a misdemeanor crime, it demanded a lower standard of proof to a win conviction. But it also carried a smaller penalty: a $250 fine and a jail term up to one year, generally limited to one sentence per indictment. Peckham had had to justify to a skeptical jury why all the fuss over such a small punishment: “We are not here to try any petty question; petty with regard to the consequences,” he’d explained in his opening trial statement, but rather “the safety, … the existence of the institutions under which the community is now organized, and under which we now live.”

5

They wanted Tweed convicted and behind bars, and this was the quickest way to get him there.

Then they had the judge, hand-picked for the job. Noah Davis, a thin-lipped, clean-shaven, 54-year-old Republican from upstate Albion, New York, near Buffalo. Davis had long, deep roots in anti-Tammany “reform” politics. He’d sat for ten years as a state judge in Albion before winning election to the United States Congress in 1867. In 1870, he’d come to New York City to join a lucrative law practice and President Ulysses Grant had made him the local United States Attorney. Both as congressman and as federal prosecutor, Davis used every chance to score points with the “reform” crowd. After the 1868 Tammany voting frauds, he’d sponsored legislation in Washington to strip local New York courts of their authority to naturalize new citizens and make immigrants wait six months after taking their oaths before being allowed to vote.

6

He’d joined the New York City Bar Association’s executive committee and served alongside Samuel Tilden, Wheeler Peckham, and other anti-Tammany activists.

When the Committee of Seventy decided to offer its own slate of “reform” candidates in November 1872 to capture the city government, it trusted Noah Davis for the empty seat on the state supreme court, making him available to preside over the Tammany trials.

7

They waited until he took office before scheduling the case. Tweed’s was Davis’ first major trial after the election.

Now, though, Davis and the prosecutors had been blocked. Tweed had hired his own team of top-shelf lawyers to defend against this onslaught. They were led by David Dudley Field, brother of trans-Atlantic Cable leader Cyrus Field. Tall and articulate, Field had made his name in the 1850s by modernizing the state’s civil and penal codes, then turned to defending Wall Street moguls like Jay Gould’s Erie Railway. Now he lived opposite Samuel Tilden on exclusive Gramercy Park and catered to one of America’s richest clienteles. Joining Field at the defense table was John Graham, an experienced trial tactician, and six others lawyers including 28-year-old Elihu Root, a future Secretary of War, Secretary of State, and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

F

OOTNOTE

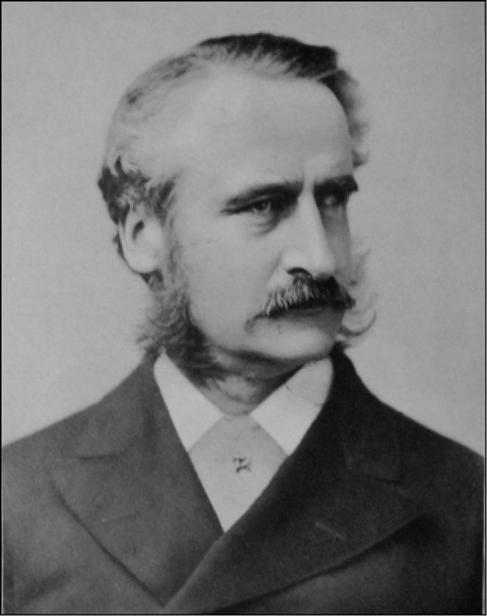

Judge Noah Davis.

Lawyer Wheeler Peckham.

From its start, Tweed’s trial had been an eye-catcher. Boss Tweed was an American living legend in 1873. Thomas Nast’s

Harper’s Weekly

cartoons had made him a national icon, the fat, thieving politician with the diamond pin. Sensational stories had pumped estimates of his Tweed Ring’s supposed thefts to $60 million or more, an amount that dwarfed every other scandal in the country’s history, be it the Whiskey Ring, Credit Mobilier, or Civil War profiteers. Newspapers touted Tweed’s personal fortune at $20 to $25 million

8

—ten times higher than Tweed’s own sworn valuation of his property at $2.5 to $3 million at its height. Frontier outlaws like Jesse James and John Wesley Hardin might terrorize the west by robbing trains and murdering townsfolk, but they didn’t live like kings in Fifth Avenue mansions. No dime novels appeared to glamorize Boss Tweed. Instead, Nast in his cartoons now portrayed the ex-Boss as a beaten, humiliated oaf sitting amid ruins.

Once the trial began, prosecutors had produced two star witnesses: First came Samuel Tilden, now a rising political celebrity as state legislator and likely next governor of New York State. Tilden had seized the chance to appear before the galleries to testify on his now-famous chart tracing over $1 million in county Tax Levy payments directly to Tweed’s personal account at the Broadway Bank. Tilden drew unintended laughs when asked in cross-examination if he’d had any “antagonisms” against Tweed. “We haven’t sympathized very much,” he said. “But I never had any malice toward him.” He mentioned his opposition to Tweed’s 1870 charter but insisted, “I acted on my own hook—an independent personal hook.”

9

The other surprise witness had been John Garvey, the “prince of plasterers” whose $2.8 million in inflated claims had been a mainstay of the

New-York Times

Secret Account stories. Garvey had fled the country to Switzerland after the disclosures but now, a year later, he’d come back to testify against Tweed and Oakey Hall. Prosecutors had promised him immunity and hadn’t asked him to return a penny of his ill-gotten gains. Tweed grew so angry at Garvey at the trial that, during one recess, he’d followed Garvey into a courthouse lobby and loudly chewed him out. Asked about it by reporters, Garvey refused to repeat Tweed’s exact words except to say “His language was blasphemous.”

10

Tweed’s defense lawyers had called only a handful of witnesses. Instead, they’d relied on logic. No evidence had shown that Tweed had intentionally stolen anything, they argued. His acts were ministerial. Tweed was no auditor and had no ability to look behind the claims presented to him. If anyone was guilty, they explained, it was contractors like Garvey who’d submitted the inflated bills or James Watson, the dead county auditor, who’d prepared the fraudulent paperwork.

The strategy worked. Tweed sat in court each day with his sons looking serene and bored. Asked how he was holding up, he’d whisper “Oh, I feel all right, thank you” or “I’ll feel better when it comes my turn to put witnesses on the stand.”

11

After Judge Davis had sent the case to the jury, Tweed waited in the Courthouse lobby hobnobbing with reporters and politicos until after 11 p.m. that night, talking with anyone who’d approach him, smiling and shaking hands.

Then, the next morning, the jury had announced its stalemate: no conviction, no acquittal. Within minutes, Peckham, the lead prosecutor, had stood up in the courtroom and voiced his indignation. “We… move the immediate trial of the case again, at the present moment, and ask the court to direct a panel of jurors to be summoned and proceed with the trial.” But Tweed’s lawyer David Dudley Field recognized the bravado as pure bluster. He too stood up and addressed the court. “We think, You Honor, this request is novel and remarkable,” he said calmly. “We are all exhausted.”

The judge agreed reluctantly. Davis had other trials to preside over that winter, including murder cases carrying death penalties. And the prosecutors needed time to assess the damage and lick their wounds.

After court adjourned, Tweed led an entourage of well-wishers out onto the icy sidewalk and up Broadway to his office on Duane Street where he spent the afternoon entertaining them, doubtless opening the old liquor cabinets for a round of drinks and cigars. “I expected an acquittal,” he said. “What it was all done for is to harass and persecute me.”

12

Most of the talk that day centered on the jury and its stalemate. Prosecutors speculated openly that Tweed must have paid a handful of them to produce the deadlock, though several jurors denied any outside influence. Tweed saw it differently: “I only know what they tell me. What they say is that they stood eleven for acquittal and two for conviction.” Reminded that there were only twelve jurors, not thirteen, his blue eyes twinkled. You’re forgetting the judge, he said. “I think Judge Davis is a very clever lawyer; but I think he was judge, counsel, witness, jury, and all in this case.”

Besides, he said, “It was only a political trial…. I know they will never get a jury to convict me.”

-------------------------

Tweed had spent a painful year waiting for his day in Judge Davis’ courtroom. During the months after his fall from power in late 1871, he’d nearly fallen apart. Booted out of Tammany and City Hall, betrayed by friends, humiliated and vilified, his mind and health had collapsed. “I myself was almost exhausted,” he later admitted. “The huge personal expense added to the other things kept me under such constant pressure that, as I have said, my brain was threatened.”

13

His career in ruins, Tweed had still come to his Duane Street office most days in early 1872 but rarely showed himself. Glum and sickly, he hid behind lawyers and refused to answer questions. His Americus Club had cancelled its annual January ball that year though it re-elected Tweed the club’s president. The

Leader

, the Tammany-sponsored newspaper that had delighted Tweed by backing him until the end, closed its doors in December 1871 when the new Sachems cut off its funding.

Early that January, Tweed had suffered an emotional jolt when his friend Jim Fisk, the chubby playboy prince of the Erie Railway, was shot dead in the Grand Central Hotel by society upstart Ned Stokes after a tawdry, public argument over Fisk’s former mistress Josie Mansfield. The assassination had shaken the city, a cold-blooded murder, and certainly made Tweed contemplate the prospect of some deranged gunman taking a shot at him as well. Hearing the news, he’d dropped everything that night and rushed to the hotel room where Fisk lay dying with a bullet in his stomach surrounded by doctors. “Well, William, you have had a great many false friends in your troubles, but I have always stood by you,” Fisk had murmured on seeing the Boss. When Tweed asked how he felt, Fisk told him a story: “When you were a boy did you ever run away from school and fill yourself with green apples? I feel just as I used to feel when I filled myself with green apples. I’ve got a belly-ache.”

14

He died the next morning of the bullet wound.

Two months later, Tammany Hall had slapped Tweed again by electing a full slate of new Sachems replete with born-again reformers: Sam Tilden, Charles O’Conor, and Horatio Seymour, all men who’d happily dance on his grave. “Tammany don’t amount to anything now,” Tweed could only grumble about his old club.

15

“I am not now in politics,” he pronounced.

16

He never bothered going to Albany to claim his hard-won seat in the state senate, fearing the legislature would only hit him with charges and investigations.

Humiliation had taken a toll on Tweed’s family as well. As he waited in New York for lawsuits and indictments, his wife Mary Jane ran out of patience. She’d left him to cross the ocean for an extended tour that summer in Europe, far from the local hysteria and her disgraced husband. She brought along their son William Jr. and his family. Tweed claimed later that the trip cost him a small fortune, $30,000, coming on top of legal bills and shrinking investments. He’d already transferred virtually all his real estate to his son Richard who now owned his Fifth Avenue home, his Duane Street office, his carriage, his upstate farm and his yachts. Tweed kept only a few land parcels in Queens and Putnam counties.

17

To raise cash, he’d even put the top story of his Duane Street office up for rent.

With money tight and friends scarce, he had to ask his son Richard to help keep him out of jail by becoming his bondsman for $1.2 million worth of bail; Jay Gould had withdrawn from Tweed’s bond in November after prosecutors had threatened to interrogate him under oath about his Erie Railway financial schemes.

18