Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (43 page)

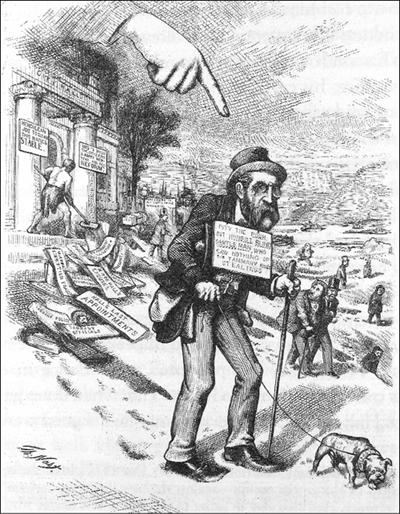

Nast’s “Finger of Scorn” following A. Oakey Hall.

Harper’s Weekly, January 4, 1873.

All that year, Tweed could only watch helplessly as reformers tore apart his political machine. Oakey Hall had managed to finish his term as the city’s mayor, but only after surviving an impeachment attempt

F

OOTNOTE

and two criminal trials. Prosecutors had presented no evidence in either of the mayor’s trials tracing city funds to him as Tilden had done with Tweed or showing that Hall knew that the warrants he’d signed were frauds, the same problem of criminal intent that had frustrated Hall’s original grand jury. Still, prosecutors were busily planning a third attempt to put him in front of a jury.

After Elegant Oakey had stepped down from the mayoralty on New Year’s Day, 1873, Thomas Nast had produced a

Harper’s Weekly

cartoon showing him leaving City Hall followed by a giant hand floating in midair and pointing a finger down from above: “The Finger of Scorn shall follow them, if law (sometimes called justice) can not.”

19

Nast would make his “finger of scorn” a regular feature in his cartoons following Hall, Tweed, and the rest. Hall didn’t seem to let it bother him, though. In late January that year, he slipped on an icy New York sidewalk and suffered a painful broken leg that crippled him for weeks. Still, he made a joke of it: “I am inundated with ball tickets from around the country, two or three being appropriately in aid of hospitals,” he wrote in a letter. “In every way I realize I am like poor France —- disordered—and especially in the Bonepartes.”

20

At the same time, Tweed saw Samuel Tilden use his new perch in the Albany legislature to destroy Tweed’s judges, long a pillar of his New York power. In quick order, Tilden had led the state assembly in bringing charges against George Barnard, John McCunn, and Albert Cardozo, demanding impeachment of each. Cardozo resigned after a long hearing.

F

OOTNOTE

McCunn died of heart failure a few days after being unanimously ejected from the bench in July, with only Tweed and Jimmy O’Brien absent from the vote. The state senate convicted Barnard after a five week trial in August on charges of favoritism, conspiracy with Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, and conduct unbecoming a judge. His 1871 betrayal of Tweed by granting the reformers their original anti-Ring injunction won him no sympathy now.

21

Meanwhile, Tweed saw the public treating his enemies as heroes, saviors of civic morality for having toppled his Ring. Thomas Nast ranked first among equals in this pantheon. His

Harper’s Weekly

cartoons had made him a national celebrity. Nast had visited Washington, D.C. in February 1872 and received a royal welcome. President Ulysses Grant himself had led the applause by inviting him to an intimate family dinner in the White House. Nast savored the limelight. “I had a very pleasant chat with [the president] about everything in general, and I was very much pleased with the open way in which he spoke to me,” he wrote home to his wife Sarah that week. “Everybody knows me, everybody is glad to see me, everybody thanks me for the work I did during the Tammany war.”

22

Nast visited Capitol Hill where leaders invited him to step out onto the House and Senate floors. He dined with House Speaker James G. Blaine and Vice President Henry Wilson and heard flattery from dozens of senators and cabinet members eager to see their faces in his cartoons.

In New York City, voters had elected William Havemeyer, the seventy-year-old former sugar merchant who’d co-chaired the reform Committee of Seventy and pressed Slippery Dick Connolly to surrender his Comptroller’s Office to reformers, their new mayor to replace Oakey Hall.

F

OOTNOTE

And Jimmy O’Brien too would soon enjoy his reward for leaking the Tammany Secret Accounts to the

New-York Times

: a seat in the United States Congress.

Tweed’s topplers literally fought over the franchise. When Samuel Tilden at one point appeared to claim too much credit, the

New-York Times

scolded him for blowing his own horn. “[Tilden] denounced [Tweed only] when it was no longer dangerous to denounce,” it proclaimed in late 1872, reminding readers of Tilden’s silence through much of the fight. “Just at present it is a comparatively comfortable thing for… Mr. Tilden… to throw mud on the grave of the Tammany Ring.” Instead, the

Times

took credit for having challenged the Boss at his height. “Mr. Tilden was throughout this period as quiet as a mouse,” it claimed. “He cut loose [from Tammany] in the very nick of time to save his own reputation.”

23

Tilden, cultivating his own rising prospects, jumped at the chance to respond by scribbling out a fifty-two page dramatic narrative detailing his own heroics in the fight, called “

The New York City ‘Ring:’ Its Origin, Maturity and Fall.

” He blanketed the state and country with copies.

24

Tweed, the arch-villain, couldn’t escape being made an issue even in the oddball 1872 presidential campaign that pitted President Grant running for reelection against Horace Greeley, the eccentric

New York Tribune

publisher running as a “Liberal Republican” (Republicans who considered Grant too corrupt) and Democrat.

F

OOTNOTE

Republicans turned reality on its head by claiming a connection between Greeley and Tweed and smearing him over it, ignoring Greeley’s years’ of fighting Tammany voting abuses long before Nast or George Jones ever got involved. Not only had Greeley accepted Tammany support in the 1872 campaign, but Republicans dug up evidence that he’d once invested in a business venture, “The Tobacco Manufacturers Association,” that included Tweed as a partner. They used it mercilessly to whip the Sage of Chappaqua.

25

Nast turned loose his talented

Harper’s Weekly

pencil to crucify Greeley in cartoons that portrayed him and Tweed as bosom buddies: In “The Cat’s Paw,” he showed Tweed the cat holding Greeley the kitten in full embrace. In “Save me from my tobacco Partner,” he placed Tweed peering over Greeley’s shoulder as a grinning cigar-store Indian in front of the “Tweed, Greeley, Sands, & Co. Tobacco and Snuff Factory” while a policeman carries “Warrants for Arrest of all the Tammany Ring Thieves,” as if Greeley were one of them.”

26

“I have been so bitterly assailed that I hardly know whether I have been running for the Presidency or from the Penitentiary,” Greeley wrote in a letter shortly after losing the vote.

27

He died a few weeks later.

As the world turned around him, Tweed could only sit and wait for his day in court: “the biggest club in New York could not drive him away,” his lawyer John Graham assured reporters after one of the endless rumors of Tweed’s imminent flight.

28

He waited for a full year, until January 1873 when finally it came. Now, having survived the seventeen-day trial in Judge Noah Davis’ courtroom and having escaped conviction, he saw a ray of light. The state’s $6.3 million civil suit against him had come up in Albany and Tweed’s lawyers had managed to stop it in its tracks as well, tangling it up in legal appeals over jurisdiction.

29

Tweed could win this fight after all. He seemed to find a new lease on life, even though the verdict, a hung jury, meant that prosecutors could try him all over again.

Feeling free and vindicated, Tweed decided to travel. He left New York City in April 1873, two months after the trial, and headed east to Boston with his wife Mary Jane and two of their children. Then he went to Chicago. In the summer, he visited California. One published report that spring placed him as far away as Ontario, Canada, supposedly preparing to sail to Europe. Instead, each time, Tweed surprised critics by coming home back to New York City.

30

He spent languid days that summer at the Americus Club on Connecticut’s Indian Harbor enjoying its panoramic vistas of the Long Island Sound and afternoons at his Greenwich estate tending his garden: vines, figs, and flowers. For privacy, he’d built a fence around the Greenwich property complete with iron gate and two iron dogs. The thoroughbred horse “Boss Tweed” still won two-mile races at Jerome Park in the Bronx but Tweed himself never showed his face there. In July, his 81-year-old mother, Eliza, died; she’d been living in an old home on East Broadway where Tweed visited her every week but kept her ignorant of the scandal.

In the fall, he took time even to comment on politics, spouting opinions as if he still held power at Tammany. Republicans had lost badly at the polls that year after the October collapse of Philadelphia’s Jay Cooke & Company, the country’s richest private banker, sparking a massive financial crisis. The “Panic of 1873” had forced the New York Stock Exchange to halt trading for ten days, hundreds of firms to declare bankruptcy, and thousands to lose jobs. “[B]read and butter is one of the most potent questions in politics,” Tweed lectured like a professor when asked, “and when I had any influence that question always received my earnest consideration.”

31

If Tweed relished his freedom, perhaps he recognized its transience. Prosecutors and reformers recoiled at the spectacle of the criminal Tweed as a free man, prancing about the country, flouting his wealth, speaking his views. Lawyers and politicians who’d built their “reform” careers on denouncing him found it an embarrassment; Tweed’s freedom only exposed their own failure to convict him. Their defeat in Judge Davis’ courtroom the prior January only whetted their appetites for a second or even a third attempt to put him behind bars. Wheeler Peckham openly complained that he’d lost the first trial only because the jury had been “corrupt.”

32

In February, a new grand jury brought four more indictments against Tweed, Connolly, Woodward, and Ingersoll, forcing Tweed to appear before Judge Noah Davis yet again to plead his innocence. By November, the prosecutors were ready for a second bite at the apple.

-------------------------

Tweed’s second criminal trial began almost ten months to the day after he’d escaped the first on a hung jury. Judge Noah Davis presided again, having just completed the trial of Ned Stokes for the murder of Tweed’s friend Jim Fisk. The jury had convicted Stokes of manslaughter and Davis had sentenced him to four years in the state prison at Sing Sing. For Tweed’s case, the courtroom again buzzed with excitement, jammed with newspaper men from across the country, teams of expensive lawyers, and hordes of curiosity seekers.

This time, though, things turned sour from the outset. On the first day in court before the trial had even begun, Tweed’s lawyers launched a radical strike. They handed Judge Davis a petition charging him with bias and requesting he disqualify himself from the case. Davis had formed an “unqualified and decided opinion unfavorable to the defendant,” they argued, and could not preside over a fair trial.

33

The strategy backfired. The petition’s last-minute timing made it look like a cheap delay tactic and a personal smear of the judge. Davis glowered with anger. “[S]ome of its statements are entirely inconsistent with the truth,” he snapped in open court, glancing at the document for the first time. “One statement is entirely untrue.” Apparently flustered, he recessed the court for an hour to confer with other judges, then came back and took a hard line: “I shall proceed with the case,” he insisted, because “self-respect” demanded it, but he reserved the right “to vindicate the dignity of the court and the profession itself from what I deem a most extraordinary and unjustifiable proceeding.”

34

But he refused even to discuss the bias issue until

after

the trial.