Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (48 page)

Given the freedom of the town, Tweed and Hunt moved into a local rooming house, the

Hotel de Shy

, while waiting for Spanish authorities to resolve their status. The town of Santiago de Cuba offered many charms: walks by the harbor, carnivals in the square, and receptions at the hotels. As “Secor,” Tweed enjoyed socializing with others prisoners, mostly American, French, and English merchants whose ships likewise had run afoul of customs officers. He celebrated the Fourth of July with fireworks from the balcony of the

Hotel Lascelles

and even hired a local customs clerk to teach him Spanish. “As soon as I got free I pitched in to study the Spanish language, and kept at it with as much intentness as I ever did to make a political point,” he’d say later.

14

He kept his distance from strangers, though, always fearful of being recognized. “I felt indisposed to talk, to meet acquaintances,” he explained.

15

During those weeks, Tweed also took time to read and hear about curious goings on back in his own country. His own escape seemed forgotten, eclipsed by newer, more exciting events. America was celebrating its Centennial birthday in 1876; a great exhibit in Philadelphia was drawing 200,000 visitors and thousands came each day to Washington, D.C. to celebrate at the White House and on Capitol Hill. News from the western frontier had shocked the country that month: General George Armstrong Custer, commander of the Seventh Cavalry, had been massacred along with two-hundred-and-fifty of his soldiers by Sioux Indians in the Dakota territory near the Little Bighorn River.

Even more striking to Tweed was the news on American politics: Democrats meeting in St. Louis, Missouri, that summer had nominated as their candidate for President of the United States a curious choice, Tweed’s old nemesis Samuel Tilden.

He also learned something else: He’d been spotted.

-------------------------

Samuel J. Tilden looked older now in 1876 after two years in the state legislature, two as governor, and months plotting for the presidency. Age had turned his hair gray, set against his formal black suits and stiff while collars. As governor, he worked long hours, straining his eyes and suffering chronic indigestion. He demanded as much from his staff. When a young lawyer hired to help on the Tweed case complained to him once about conflicts with other work, Governor Tilden lost his temper. “Sir!” he’d screamed, “a man who is not a monomaniac is not worth a damn!”

16

As governor, Tilden had set up residence at the state capitol in Albany, renting a large home on Eagle Street and asking his sister Mary Pelton to come and manage his household. Rumors circulated in late 1875 that he’d suffered a stroke or “softening of the brain.” Even close friends believed it for a time because of Tilden’s chronic poor health. But he still kept a regimen of daily horse-riding, purchasing a sealskin coat to brave even the coldest Albany winter days, earning him the nickname “Sealskin Sammy.”

Tilden had won the New York governorship by 50,000 votes in 1874, as big a margin as Tweed had produced for John Hoffman in 1868 with all his shenanigans. Tilden used the perch to strengthen his crime-fighting credentials by tackling the upstate “Canal Ring,” a cabal of contractors and legislators who embezzled millions of dollars on fraudulent bills for repairs to the Erie Canal and other waterworks, not unlike Tweed’s bill-padding in New York City. He’d built his presidential campaign with his usual painstaking care. He’d placed in charge two close confidantes: Abram Hewitt and Edward Cooper, both Gramercy Park neighbors and long-time allies from railroad and coal investments. He organized a “Literary Bureau” to pump out friendly news stories and pamphlets and had a special telegraph wire laid from St. Louis, where Democrats planned to hold their nominating convention, to his governor’s mansion in Albany.

He campaigned on a single theme: reform! Tilden had found his moment.

Scandals had shaken America in the 1870s, making earlier swindles—Civil War-era profiteering, local graft, or anything else—look like child’s play. Critics called it the “Era of Good Stealings,”

17

a time of unprecedented graft at every level of government, especially in Washington, D.C. Scandal had tarnished President Ulysses Grant’s administration to the point that “Grantism” became an insult. Grant appeared personally honest but surrounded by looters. The Whiskey Ring frauds reached Grant’s own personal secretary Orville Babcock and Indian land scandals forced the impeachment of his Secretary of War William Beklnap. The Credit Mobilier implicated dozens in Congress, not to mention Congress’ own “salary grab,” the James G. Blaine “Mulligan Letters” scandal, and graft by reconstruction governments in the South.

F

OOTNOTE

Who better to clean up the mess than Sam Tilden, the honest man who’d beaten the blackest corrupt conspiracy of them all: Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall.

Tilden’s 1876 Democratic platform called for “reform” of almost everything: the civil service, the currency, homesteading, taxes, and crooked politicians. Republicans too saw the light and nominated their own self-styled “reformer,” Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes who promised to drain Washington’s political patronage swamp. The holier-than-thou “reform” versus “reform” contest made practical politicians on both sides hold their noses.

F

OOTNOTE

Among Democrats, Tilden only serious opposition came from a small circle of people who knew him best, old New York friends like August Belmont, Augustus Schell, and Tammany Hall’s John Kelly, an early ally who’d grown tired of Tilden’s arrogant style. Tilden’s agents managed to gag them all in St. Louis at the convention; they held New York’s seventy delegate votes in line with a strict Unit Rule and, when Kelly tried formally to attack him in a speech to the convention, they had him ruled out of order. Tilden won the nomination easily on the second ballot, defeating Indiana Governor Thomas Hendricks whom he chose as his vice presidential running mate, but Kelly never forgot the insult.

Now, with the nomination in hand, Tilden found himself dogged by old news: Tweed. With bitter irony, Republicans were trying to smear him by tying him to the same Tweed Ring he’d helped destroy.

Tilden had gladly testified at Tweed’s

abstentia

trial in New York City the prior February hoping to remind voters of his role in toppling the Ring. On cross-examination, though, Tweed’s lawyer David Dudley Field had embarrassed him by producing evidence painting he and Tweed as best of friends: an 1866 letter from Tilden inviting Tweed to join him at a Philadelphia political rally, a letter form Tilden requesting for a job for a mutual ally, and a $5,000 check Tweed had given Tilden as an 1868 campaign contribution. “You and Tweed went to Philadelphia and stood shoulder to shoulder to fight for the constitutional liberty of this great republic?” Field asked mockingly at one point, prompting waves of laughter in the courtroom as Tilden bit his lip and forced a smile but didn’t answer.

19

Tweed’s escape from Ludlow Street Jail had caught Tilden unaware. His first reaction was to insist that the getaway was not his fault, which would have been a severe embarrassment. “The sheriff alone is responsible,” he told reporters, “the whole responsibility is on the sheriff.”

20

He must have scowled at seeing the latest cartoon from Thomas Nast in the July 1, 1876

Harper’s Weekly

. Called “Tweed-le-dee and Tilden-Dum,” it showed he and Tweed in cahoots once again. In it, “reformed” Boss Tweed (dressed in a striped prison suit with diamond on his chest and a belt saying “Tammany police”) is seen arresting two young boys from the street. “If all the people want is to have somebody arrested, I’ll have you plunderers arrested,” the “Reform Tweed” says, “You will be allowed to escape; nobody will be hurt, and then Tilden will be in the White House, and I to Albany as Governor.”

21

Still, with Tweed on the run and in hiding, at least Tilden could count on Tweed’s mouth being shut for the rest of the campaign. He could rest easy on that score. Or at least so he thought.

President Ulysses Grant had mostly stayed out of the contest. Looking forward to retirement with just eight months left as president, Grant was spending a quiet summer at his vacation home by the seashore at Long Branch, New Jersey, far from the White House. Grant did not especially like Rutherford Hayes whose “reform” talk often sounded like personal backbiting, but he didn’t like Tilden either. That summer, Grant became intrigued over a possible role he could play in the contest. His State Department had picked up the trail of Sam Tilden’s nemesis on the run. Grant, like other Republicans, savored the prospect of Boss Tweed, captured and in their custody, being used as a weapon against Tilden. And for Grant himself to get credit for catching the fugitive would be a welcome feather in his hat.

Grayer and stouter now than during his days as Civil War commander, Grant had learned of the discovery in July. Henry Hall, the American Consul in Havana, had contacted his State Department superiors on June 23 to report the landing of the two Americans “John Secor” and “William Hunt” aboard a schooner from St. Augustine, Florida. Secor, being over fifty years old and in poor health, made an unlikely “filibusterer” but Hall suspected he might be a fugitive. Secor and Hunt both carried passports issued in Washington, D.C., on April 3, 1876 but with no visas. The passports had been mailed to “Jon Brown, New Court House, New York City.”

22

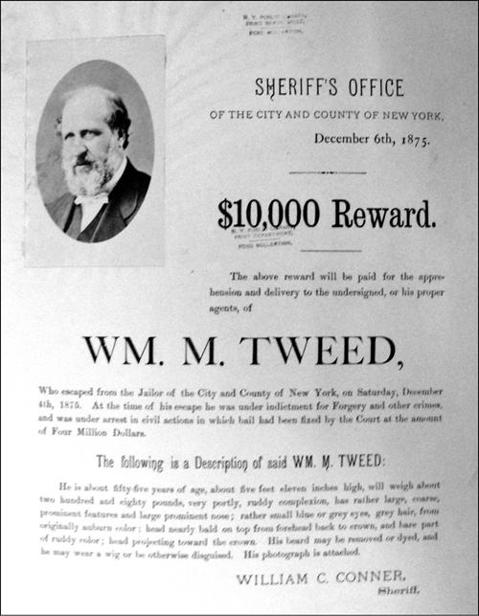

A few days later, Hall had alerted his colleague Alfred Young, the consul in Santiago de Cuba, that “Secor” might be the infamous Boss Tweed of New York City. He enclosed a photograph and the description of Tweed from the New York sheriff’s wanted poster

23

and asked Young to investigate. A few days later, Young confirmed: “Vessel Arrived Safely”—code for Tweed—though he noted separately that Tweed appeared much thinner now, suffered from heat and disease, and might die if detained by police.

24

Hearing the news, Grant’s Secretary of State Hamilton Fish ordered that a trap be set. “If Secor is Tweed and is still in Cuba ask [the new Spanish] Captain General Jovallar would he deliver Tweed to United States officials if a ship was sent to Santiago,” Fish directed.

25

Jovallar apparently agreed—despite the absence of an extradition treaty—but said he needed time to confer with his superiors in Madrid. Meanwhile, Hall made arrangements to identify the fugitive, take him into custody, and inform the press at the proper time.

Everything seemed ready for the takedown except for one: Tweed himself had other plans.

-------------------------

It’s not clear how Tweed learned about the trap. “No sooner had I got to Havana than old Jovellar learned in some way that I was a nice fat goose that he could pluck to feather his nest,” he’d claim later.

26

If Tweed did pay the General a hefty bribe, then he got good value for his money. But he got even more from a use of simple charm to win another ally: Alfred Young, the helpful American Consul in Santiago de Cuba.

Young would later admit knowing Tweed’s real identity almost from the start. Hunt had told him, he said, and Tweed had spilled the beans to his wife. In fact Mrs. Young, the consul’s wife, became quite taken with the elderly fugitive she enjoyed socializing with that summer around the bar of the

Hotel de Shy

and at diplomatic receptions. “[H]is wife had great influence over him,” the State Department would later conclude of Alfred Young, “[and] she was very much interested in Tweed’s condition.”

27

Tweed, recognizing the closing net, decided he needed to leave Cuba immediately and booked passage on a Spanish ship bound for Barcelona and Vigo, the

Carmen

, paying $548 for himself and Hunt. He had a problem, though. The ship was scheduled to leave port on July 22 and Spanish authorities still hadn’t approved his passport. He remained a prisoner in Santiago. Tweed approached the

Carmen

’s captain and convinced him to wait a few days, agreeing to pay the demurrage, or harbor fees, while the ship sat idle. But that wasn’t enough; he needed to push the Spanish authorities to release his passport.

Here, Alfred Young, the American consul, proved very helpful. At Tweed’s behest, he personally applied to Spanish officials for “Secor” and “Hunt’s” passports and found he was getting help from unexpected places: The Captain of the Port, who reported directly to General Jovellar, “had rec’d orders to let Secor [Tweed] go wherever he pleased,” Young explained later, and the local British vice consul too had heard appeals from New York City business friends to help Secor.

28

Someone was pulling strings from high places.

Within a few days, Young had broken the logjam and presented Tweed and Hunt their passports. Finally free to leave, Tweed signaled the

Carmen

’s captain to set sail. But Young hadn’t finished yet. He did Tweed two more crucial favors: He helped Tweed financially by changing $620 in American greenbacks into Spanish gold and converting a $2,200 bank draft into local currency, sending some of the cash back to Tweed’s son William Jr. in New York City. Then he misled his superiors. He waited until the eve of the ship’s departure before telegraphing Henry Hall in Havana that Tweed was about to leave. Hall, receiving the telegram at 6:30 pm, commandeered a carriage and galloped the eight miles to General Jovellar’s home outside Havana to request he immediately detain “Secor.” Telegraphs flashed orders to Santiago de Cuba and a warship was sent in pursuit, but the

Carmen

had reached the open ocean.