Brass Diva: The Life and Legends of Ethel Merman (25 page)

Read Brass Diva: The Life and Legends of Ethel Merman Online

Authors: Caryl Flinn

Of course, people knew Ethel to use language and jokes offstage that

would make the proverbial sailor blush, apparently outdone only by Tallulah

Bankhead. Onstage, Ethel tamed those qualities without ever apologizing for

them. "It is rough and rather coarse in spots," ran a DuBarry review, "but the

very frankness of its bawd[iness] and the blithe refusal of the stars even to

admit that there is anything to be abashed about should disarm the sternest

moralist."63 What Ethel did was create a sense of both bawdiness and good

clean fun.

What was beginning to intensify was a lifelong tension between Ethel's

skills as an attractive singer and those of a boisterous comic. In the late 1930s

in shows like Stars in Your Eyes and DuBarry, Ethel was allowed to be both. (A

female critic even described Ethel's DuBarry as "gorgeously comic." )64 But the

balance would prove hard for her-or for any other female performer-to keep.

Throughout the 1930s, Merman's musical comedies had contained risque

elements, partly the vestiges of vaudeville and burlesque comedy, partly the

influence of costars such as Lahr, Durante, Haley (vaudeville hams all), the

characters she portrayed (gangster molls, brassy single women), and the lyrics

of her songs ("Anything Goes," "Eadie Was a Lady"). In the early '3os, critics would blame the book or the lyricist if things bordered on racy. By now,

at the end of the decade, such complaints were beginning to spill over, indirectly, onto performers. Ethel was lucky to avoid the slime.

As far as Broadway musicals were concerned, the complaints over

DuBarry's rough gags suggest two things. First, that the lighthearted book

musical was getting tired. Broadway audiences had experienced a decade of

light escapist fare in the '3os, but they had also experienced the novelty of

shows like Porgy and Bess. The second issue involves the entertainment industry's relationship to world events at hand. By the time DuBarry ran, war

was consuming Europe, and despite the official isolationism of U.S. policy,

concern was mounting for the situation and for the refugees and orphans that

fascism was already churning out. Stars like Merman were already going to

rally after rally to lend their names to fund-raising and relief efforts.

In times like this, lighthearted fare can turn on itself, for it's a fine line that

separates escapist, pleasurable diversion from entertainment that is out of touch, inappropriate, or insensitive. DuBarry ran at a time when Life with Father, Too Many Girls, Leave It to Me! and Pins and Needles were also on Broadway, and while none tackled the war or other current events, critics rightly

viewed DuBarry as one of the more dated shows. It took no risks except that

of not taking any.

As the United States grew more sensitized to the conflict, the values it

wanted to uphold grew more conservative and old-fashioned. The obvious

irony here is that "older fashioned" forms of comedy were becoming less acceptable, deemed in poor taste: vaudevillian double entendres were flying in

the face of family-friendly fare and a nation wanting to unite through homespun humor and honorable women. Sex found expression in monogamous

marriage, and jokes were of the "good, clean fun" variety. Obviously this isn't

what Broadway theater (and to a reduced extent, film and radio) was going

to provide in toto; after all, "adult" stars like Tallulah Bankhead, Beatrice Lillie, and Noel Coward were in their prime.

Despite Americans' reelection of the liberal FDR to a third term in 1940,

a more conservative ethos ruled the day, and by the time of DuBarry, entertainment was a more conservative beast than it had been during the days of

Take a Chance. In regard to Ethel, this meant several things. First, we are seeing the early signs of her spirited characters becoming more politicized; second, by contrast, that "all-American girl-next-door" persona is mutating into

a tough-talking woman of experience, an image enhanced by stories of her

offstage battles, such as those with Durante and Hope. Thus, while Ethel still

embodied wholesome energy and verve, the good stenographer was giving

way to a brassier, harder persona, a trend that intensified as years went by. But

bright or tarnished, underneath was a generous, even vulnerable, woman,

whether onstage or off.

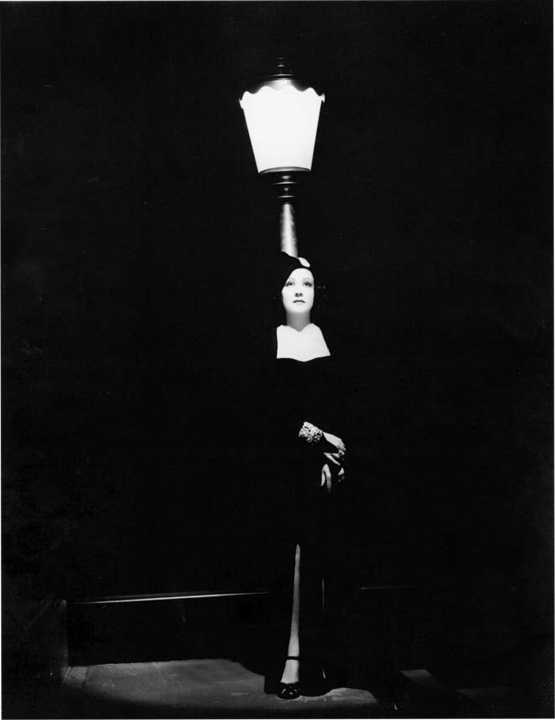

Ethel Merman at lamppost, 1930s. Courtesy of Sydelle Kramer.

Ethel with the scrapbooks maintained by

her father. Courtesy of the Museum of the

City of New York.

Ethel as a young girl with an unidentified boy. Courtesy of the Museum of the

City of New York.

Ethel, age three, with her cousin Claude

Pickett (standing). Courtesy of the

Museum of the City of New York.

Ethel the stenographer, mid-192os.

Courtesy of the Museum of the City of

New York.

A modest flapper. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

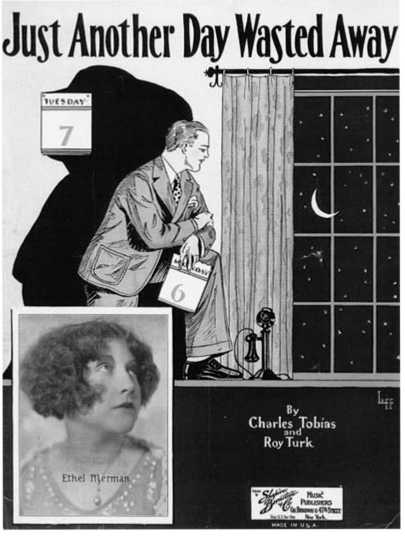

Sheet music featuring Ethel

Merman, 1927. Courtesy of the

American Musical Institute.

At the radio mike, early 1930s.

Courtesy of the Museum of the

City of New York.

Ethel arrives in Los Angeles, 1933. Syndicated ACME photograph;

courtesy of Al F. Koenig Jr.

Ethel and Leslie Stowe in the expressionist short Devil Sea, 1931. Author's collection.