Breaktime (2 page)

Authors: Aidan Chambers

Most unsettling of all has been the souring relations between his father and himself. They have reached that pitch where neither can speak civilly to the other for more than a minute or two; more usually, sharp words and barely controlled insults serve as their daily discourse. It pains Ditto; he is certain it pains his father. But the hurt is apparently incorrigible.

Pedalling steadily towards his next parental encounter, Ditto’s thoughts travel in another direction. He remembers a time before his father’s illness, before, even, he himself had left primary school.

A photograph in Mother’s box of family pictures, me thin as a lamp-post on the sprout, ten years old, holding a fishing rod and grinning triumphant at the camera, a dace the size of a stunted sardine hanging from the end of my rod, the dace wriggling still when the picture was snapped by a nearby fisherman who

obliged

so that Dad could be in the picture too and he is there behind me and to one side, my left side I think, right as you look at the picture . . . Dressed in his work suit, grey and a bit baggy, but a starched white shirt collar and neat black tie, always neat your dad they used to say always just right, his hair still black then, grey now since his illness, and his face full still, moon round still, and used to shine blood-orange red after he’d had a few at the local in the evening or before dinner on Sundays, doesn’t bother now, can’t I suppose . . . After the picture was snapped he rubbed his hands together as though trying to crack the finger bones, and smiled to himself in the way he does, did, when pleased or proud, he was pleased and proud that day because I’d caught that dace my first and he had been there to see it and have the moment recorded, the capture captured, memorialized by the obliging fisherman.

That same day, yes that’s right, just after slaughtering the dace with a sharp blow on its head we saw a snake swimming down the river its head above the surface like a submarine periscope. It turned just below us and writhed ashore entirely confident, not a jot of notice paid us who were standing there aghast agog me, my father, the nearby obliging fisherman, my camera still in his hands. An excited shouting boy came downriver with the snake, skipping along the bank crabwise, pointing at the riverborne reptile and bellowing Look, look, a snake, see, a snake. The minute the snake got ashore this boy and me we fell upon it hurtling stones and beating it to death in the end savagely—were we scared or were we hunting—and while we were assaulting it Dad said You shouldn’t kill it. It’s only a grass snake you know not poisonous . . . Afterwards he was silent did not celebrate the occasion with wringing of hands and did not join this stranger boy and myself who persuaded the obliging fisherman to take another snap of the pair of us each with a finger and thumb in tentative apprehension holding the snake by its tail end dangling dead between us as we had been big game hunters in safari Africa and our grins are wide and fevered.

If not the snake why the dace? . . . Next day I was disappointed,

the

snake was like a deflated balloon after a party, but a wrinkled memory of itself not exciting or fearsome any more nor wondrous neither, just empty, and pungent . . . Dad reverently wrapped it in old newspaper and carefully placed it in the rubbish bin.

And said nothing.

Home

Now, thought Ditto, he’ll still say nothing. Can he still?

The front door snecked behind him, its phony pane of stained glass window trembling in the concussion. He hoped the glass would shatter one day and was experimenting with various forces of slam to find breaking point. At least when the window splintered the superfluous lead would serve at last some honest purpose and save the pieces from scattering.

Coughing from the livingroom, rich, liquid, gurgling.

A deadly liquefaction, Ditto thought. He’s gargling in his own sputum.

He would have liked to climb the stairs at once to the seclusion of his room; but a sense of duty he was trying so far without success to corrupt forced him towards the livingroom. Inside, the air was greenhouse stuffy, smelt of rancid snot, stockinged feet and overheated television set. He tried not to breathe, but the only result was that finally he had to breathe more deeply still and savour the tangy odour. He sat down on the edge of the sofa, prayer-placed hands gripped between pressing knees.

‘Home then,’ the inevitable conversation began.

Ditto nodded, eyed his father for signs of prevailing mood, slumped there in his bulky armchair with its rubbed-to-the-skin arm ends, his feet resting on a footstool. At the other side of the fireplace the TV flicked its images but the sound was turned off. His father disliked TV sound; said it gave him palpitations, and that anyway he could imagine what was being said because nobody ever said much worth hearing.

‘What you done today?’

Ditto resisted the impulse to reply not much. He knew too well the fractious talk that would follow.

‘Jane Austen,’ he said, his throat stiff from restraint.

‘What did she have to say for herself?’

Ditto squinted for hint of jest behind his father’s deadpan. None was intended, sadly.

‘She’s an author,’ he said.

‘O, aye?’

‘A dead one.’

‘Is she now? So you’ve been reading all day.’

‘For exams.’

‘What’s she write about, this dead woman?’

‘It would take too long to explain.’

A long glance; a smile, sour. ‘You mean, you think I’m too thick to understand.’

Ditto knew better than to bite on that bait.

‘How’ve you been?’ he asked.

‘Fairish. Cough’s bad.’

‘Had some tea?’

‘Couldn’t be bothered.’

‘Like a cup now?’

A nod; small boy ashamed. ‘If you’re making one.’

While the kettle boiled, he standing over it, Ditto remembered another day.

He gave me a book that time, how old was I? About twelve, well I must have been twelve because it was my birthday and I had just started at sec school and was getting good reports. He was hand-wringing pleased, his lad was learning French and stuff that would help him get on in life. A proper snot I must have been. Am I still?. . . And he gave me this book, who was it by? I don’t even remember. Anyhow I thought it was some god-awful person, not to be seen reading it, and I said, I remember what I said if not who the book was written by, I said, not thinking, you don’t when you’re a kid like that, I said haughty,

Thanks,

Dad, but I can’t read this. Why not? he said his face fallen. Well at school they tell us what’s best to read and Mr Midgely, he said this writer wasn’t very good, so I don’t think I can read it you see, I said, right little snot . . . And he just looked and went out of the room, my room, my bedroom it was, I remember now, where they’d brought my presents early to please me and see me open them . . . Mother looked daggers, one of those looks she used to promise me in shops when I was very little and not behaving, If you don’t behave yourself I’ll give you

such a look

, she’d say, well she gave me such a look then, that day, my birthday, and went after Dad. I don’t remember feeling I’d said anything rotten.

Was that the start of it?

Ditto took the cup of tea to his father.

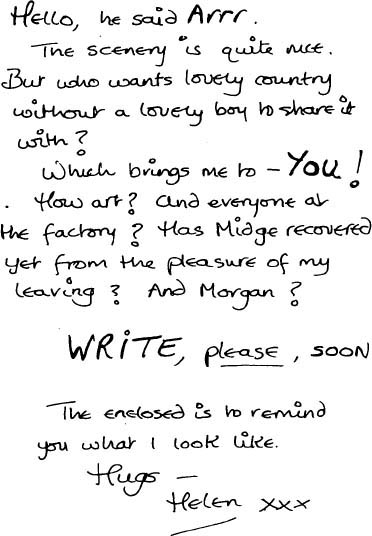

‘Ta,’ his father said. ‘And I forgot. There’s a letter for you. On the mantelpiece. Come after you’d gone this morning.’

Ditto took it. The handwriting he knew at once; knew too that he could not read this letter here, in front of his father.

‘If you’re all right then I’ll go upstairs and do some homework.’

‘Right-o,’ his father said, an agreement heavy with accusation.

Ditto’s Room

Upstairs. Front room of three-bedroom, semi-detached, late 1930s speculation-built house, half limey brick, half crumbling pebble-dash with bay-window on ground floor front room, the room below Ditto’s.

Inside Ditto’s room. Single bed with blue candlewick coverlet. Wardrobe, laminated dark oak on chipboard. Bookcase crammed with books, mainly paperbacks, case made by Ditto himself in woodwork lessons during first two years at secondary school, painted white and looking now to him a hamfisted construction for which, nevertheless, he felt a nostalgic affection. Old, real oak kitchen table, four feet by two, sanded to the bare

wood

(having once been stained dark in days when virgin wood was vulgar) and sealed with varnish; now used as desk; found by Ditto languishing on a rubbish tip.

On desk: blotting pad, pocked with surreal ink stains, doodles composed mainly of abstract combinations of squares, triangles and hachured shading: product of many hours of brooding contemplation. Portable Olympia typewriter, present from parents last Christmas. Pot, unglazed, red-fired clay bought for five pence at summer fête at school, profits in aid of Oxfam, serving now as pen and pencil holder. Seventy-second scale model of Mark V Spitfire on perspex stand. Rubber pencil eraser; chipped wooden ruler; small calendar cut from last year’s pocket diary and Sellotaped to a piece of stiffening cardboard.

The room walls: painted mat sand-brown, the ceiling mat white, the door and other woodwork gloss white. On the walls: pictures, clippings from magazines, posters, record sleeves, bookjackets. Ephemera in profusion. Mostly browned from age and sunlight (which achieved some sort of penetration between the hours of two-thirty and six,

post meridiem

).

The flat-faced window, two-sectioned. One section opening outwards gives view and vent on to arterial road leading to town (or, from, depending upon one’s need), centre of town two miles distant, edge of town one mile. His father cannot tolerate noise of traffic, preferring duller, but larger and quieter back bedroom, hence this front room Ditto’s. Window veiled by crisply starched net curtains, insisted upon by his mother (you never know what people outside might see inside). For night-time privacy, heavy chocolate-brown curtains drape the windows, floor to ceiling.

The seats. One kitchen chair, uncomfortable, at desk. One old, small, poorly stuffed armchair covered in synthetic fabric stretch-cover, bile-green, bought in Co-op sale and looking it, with bright red loose cushion for highlight. If you slouched across the thing, sitting was bearable.

Letter

He laid the letter on his desk blotter, stood staring at it a moment, savouring its possibilities. Its arrival was entirely unexpected; not even hoped for.

Then, anticipation weakening him so much his hands trembled, he took off his school jacket and tie, heeled his shoes from his feet, unhitched his trousers and stepped out of them, took up the letter again carefully, threw the candlewick coverlet aside, and lay down on his bed.

While calming his breath, he gazed closely at his name and address in the unmistakable handwriting: fluent, firm, yet still echoing a child’s awkwardnesses.

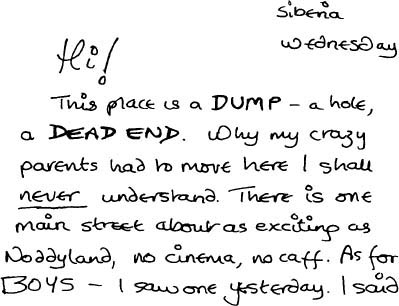

The letter, when he slit open the envelope with his right forefinger and eased the page out, was written on one side of a single sheet of school exercise paper. As he unfolded the page, a photograph fell like an autumn leaf on to his chest, picture side down. Deliberately he left it lying there while he read the letter.

Picture

Her of course, the picture is of her, of course, in colour and my god it’s her in swimsuit strip but not stripped enough, must have been taken last summer before she left while she was still

here

and I was lusting after her then and didn’t attain what I dreamt of feeling too cloddish when face to face with her but she must have known mustn’t she Morgan wouldn’t have dithered the sod not he and she would have aided and abetted him I’ll bet would she me those legs what legs what tits and a face to go with them a bit knowing though and maybe that’s what held me back though it doesn’t now you brute but this letter now maybe all the time she was waiting was wanting was after it me me her after it was she me her me her legs breasts skin face legs legs o legs her her her there there there there there there

and it’s gone all over my frigging shirt and my hanky’s in my pocket in me trousers on the frigging floor should have thought prepared but didn’t think didn’t expect her to send such a provocative picture the slut