Brown, Dale - Patrick McLanahan 03 (45 page)

Read Brown, Dale - Patrick McLanahan 03 Online

Authors: Sky Masters (v1.1)

“Safely asleep in the trunk,

Ambassador O’Day,” the man replied. “He put up quite a struggle before we could

subdue him. He will awaken in a few minutes.” The driver eased off the main

avenue toward a hotel parking lot where the car could be partially obscured,

but not appear too conspicuously isolated. He parked the car and immediately

began removing the uniform.

“What are you going to do with us?”

“Nothing,” the driver said.

Underneath the blue uniform, he wore a T-shirt with palm trees on it, khaki

shorts, and white tennis socks; he replaced the spit-shined shoes with tennis

shoes. He looked like a tourist from any number of Asian or European countries.

Gripping the .45 in his right hand, he glanced nervously at his watch, leaned

through the dividing window between the compartments, and said, “I know your

embassy tracks all its vehicles by microtransmitter, so I will not stay any

longer. I have a message from Second Vice President General Samar ...”

“

Samar

!” O’Day exclaimed. “Is he still alive? Is

he in hiding . . .?”

Samar

had disappeared the day Mikaso had been

killed. It had been assumed

Samar

was

dead, too.

“Silence,” the man said; then,

realizing he might have sounded too demanding, added, “Please.” Then, “General

Samar requests help from your government to relieve

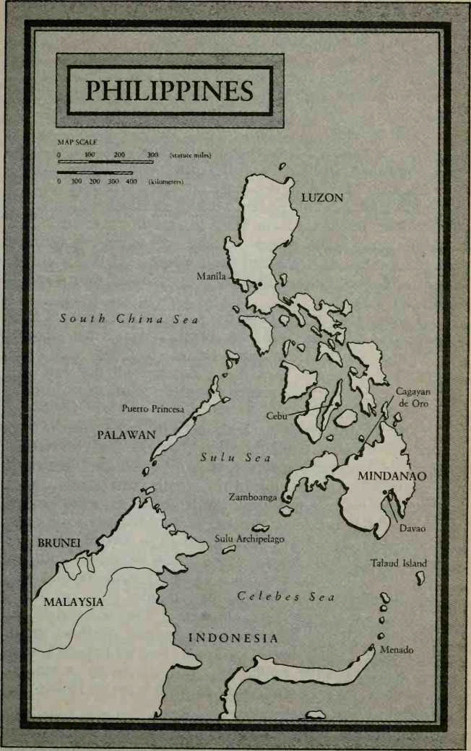

Davao

on the

island

of

Mindanao

. He is resisting the Chinese invaders but

cannot hold on for much longer—Puerto Princesa and Zamboanga have fallen, and

Cotabato and

Davao

will be next . . .”

“If

Samar

wants help,” O’Day told the man, “he had

better stop playing hide-and-seek and take control of the government. The

non-Communist citizens will follow him, but everyone thinks he’s dead . . .”

“He may be dead if you do not help,”

the agent said. “We need more than just. . .”

“Silence. I have stayed too long

already. Listen carefully. General Samar says that the

Ranger

carrier battle group will be attacked by Chinese air forces

from Zamboanga if they attempt to enter the

Celebes Sea

.”

“What?

How in hell do you know that . . . ?”

“General Samar is on

Mindanao

, organizing his people and his resistance

forces. He is carefully monitoring the Chinese military’s movements and

communications, and he concludes that on the first of October—Revolution Day—

Admiral Yin Po L’un’s forces will attack any foreign military forces that

attempt to pass near

Mindanao

.”

“But that’s crazy,” O’Day’s aide said.

“The Chinese wouldn’t be stupid enough to attack an American carrier . .

“I will not debate you. The General

has risked his life to bring this information to you—in exchange, he officially

requests military and humanitarian aid from the

United States

. Please help. Contact him at this number

immediately. Do not alert your embassy by radio or telephone; there are spies

everywhere.” The man reached down and hit the button to unlock the trunk. “Your

guard will awaken in ten to fifteen minutes; he will release you then. Do not

attempt to follow me. Please help my people.”

The man raised the dividing glass

screen, stepped out of the car, and ran as fast as he could away from the

hotel; they saw him throw the gun into a ditch before he ran out of sight.

Andersen Air Force Base,

Guam

30 September 1994

,

2331 hours local (

29

September, 0931

Washington

time)

They had kept the landing lights off

until seconds before touchdown. The only lights on around the entire base were

the runway-end identifier lights and blue taxiway lights—all “ball park” lights

on the parking ramps, exterior fights, and streetlights near the runway were

out. Looking from the cockpit, the entire northern part of the

island

of

Guam

appeared as dark and as deserted as the

thousands of miles of ocean they had just crossed.

The aircraft, as black as the

tropical night sky from which it descended, used the runway closest to the

parking area and did not touch down until nearly halfway down the two-mile-

long runway at Andersen Air Force Base so it would spend as little time as

possible exposed to view while taxiing. At the end of the runway, it taxied

rapidly across the wide north ramp to a row of large hangars and pulled

straight into the first one. The hangar doors were closed behind it seconds

later as the engines were shut down. Security patrols began an immediate sweep

of the area, using dogs and light-intensifying night-vision equipment to search

for intruders.

The interior of the huge hangar

brightly illuminated the sleek, bat-shaped outline of the B-2 Black Knight

stealth bomber. Maintenance crews checked the aircraft and immediately began

opening inspection and access panels. A few moments later the belly hatch swung

open and three men climbed down the access ladder.

As Major Henry Cobb, Lieutenant

Colonel Patrick McLanahan, and Brigadier General John Ormack emerged from the

huge black bomber, General Elliott, General Stone, Jon Masters, and Colonel

Fusco were there to greet them. “Good to see you guys,” Elliott said, shaking

each of their hands and handing each of them a beer.

“We’re damned glad to be here,” Cobb

exclaimed. “My butt is wondering if my legs have been cut off.” All three

aviators looked completely exhausted and thoroughly rumpled, but their smiles

were genuine as Elliott made introductions all around.

The formalities of every military

flight still had to be accomplished, so Elliott and the others waited patiently

as Cobb and McLanahan completed their postflight walk- around inspection of the

bomber and sat down with several aircraft-maintenance technicians to explain

the few glitches found during flight. Afterward they were taken to a conference

room at the command post, where sandwiches, more beer, and several other

members of Stone’s staff were waiting to greet them.

“I must say, this is a pretty

impressive showing,” Rat Stone said after the three crew members were settled

down. “Deploying a B-2 from

South Dakota

to

Guam

with only three hours’ notice, then flying

nonstop all the way. So what’s it like to spend nearly seventeen hours straight

in a stealth bomber?”

“The first ten aren’t too bad, sir,”

Ormack replied with a tired grin. “Henry made the takeoff and the first two

refuelings, but I was too wired to sleep. We switched just past

Hawaii

. When we got out of radio range of

Hawaii

, it was absolute murder to stay awake until

the next refueling—near

Wake Island

,

as it so happens. The last four hours were the worst—too keyed up to sleep, too

tired to concentrate, having to make those timing orbits so we wouldn’t land

too early and get our pictures taken by the Chinese spy satellites. I’m too old

for these butt-busting missions.”

“Well, you did good,” Elliott said.

“You landed right on time—the Chinese bird should be passing overhead right

about now. Unless there’s a sub out there we haven’t found yet, we may have

pulled this off—deploying a stealth bomber seven thousand miles in total

secrecy. How’s the bomber look?”

“Everything’s in the green,”

McLanahan said. “We brought spares for most of the critical components, and we

have the computerized blueprints on the PACER SKY mod installation.” He turned

to Jon Masters and said, “The system was working like a charm, Doctor Masters.

We were able to monitor some of the

Ranger

battle group clear as day. The NIRTSats found a few Chinese ships operating in

the

Celebes

, but I don’t think there’s going to be a

problem with them as long as we stay clear of them.”

“That’s exactly what we intend to

do,” Stone said. “We got a cryptic but urgent report from the State Department

that the Chinese Navy might try something against the fleet if we move into the

Celebes Sea, so except for the RC-135 overflight—and he’s been instructed to

stay at extreme sensor range from any Chinese vessels—we’re staying well away.”

“Well, the RC was still a few hours

from on-station, but he should have the Chinese ships’ position from the NIRT-

Sat—he shouldn’t have any problem staying out of the way. I recorded the

NIRTSat transmissions, and we can download it from the memory banks right

away.” McLanahan stifled a big yawn, finished the rest of his beer, then added,

“Rather,

you

can. I’ve got to get

some sleep.”

Aboard the RC-135X radar

reconnaissance plane Over the Celebes Sea, southern Philippines Saturday, 1

October 1994, 0121 hours local (30 September, 1221 Eastern time)

From thirty thousand feet, the radar

aboard the RC-135X radar reconnaissance aircraft could pick out the dense

clusters of islands, atolls, and coral reefs of the Sulu Archipelago. At the

very tip of the peninsula was the area that most of the ten radar operators on

the RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft were concentrating on.

In the center of the converted

Boeing 707 airliner was the command station, where Colonel Rachel Blanchard and

her deputy, Captain Samuel Fruntz, sat poring over a stack of four-color

charts. “Look at this,” Fruntz remarked, pointing at the tip of the Zamboanga

peninsula. “Not very subtle, are they? A whole line of vessels stretching from

the

North

Balabac

Strait

to Zamboanga.” He compared the image to

another chart. “Checks right on with that NIRTSat printout we received from

Andersen. That PACER SKY satellite is far out.”

Blanchard looked at her younger

deputy and rolled her eyes. Fruntz, Blanchard thought, was another “techie” who

believed that, whatever the newest technology was, it had to be better than any

of the “older” technology, even if the older technology was only a few years

old. Blanchard had been in the reconnaissance business for twelve years, mostly

as pilot or copilot flying EC- and RC-135 aircraft for the Strategic Air

Command—this was only her second tour as recce section commander—and she had

been dismayed at the new emphasis on space-based reconnaissance systems, or

“gadgets” as she called them. Even the latest high-tech satellites had serious

limitations that only well-equipped planes like the RC-135 or the newer EC-18s

could overcome.

Blanchard had flown or seen just

about every one of the sixty different iterations of the C-135 special

mission/reconnaissance/intelligence-gathering aircraft. The RC-135X, nicknamed

“Rivet Joint,” was the latest and best of the older RC-series aircraft; the

newer series was designated EC-18 and was a hundred times more cosmic than even

the RC- models. Rivet Joint had been designed to map out precise locations of

coastal enemy air-defense sites for targeting by Short-Range Attack Missiles or

cruise missiles that armored long-range bomber aircraft. By combining sensitive

radiation sensors with powerful radar and infrared images, one Rivet Joint

aircraft could update three thousand miles of coastal air-defense sites in one

day. Blanchard used to fly reconnaissance missions in conjunction with SR-71

Blackbird spy planes—the SR-71 would fly toward the Russian coastline until

Soviet air-defense missile-site radars activated, and then the RC-135 would

plot out all the locations of those missile sites. It was a deadly game of

cat-and-mouse that, thankfully, she had never lost.

“Hey, Sam,” Blanchard told her

younger partner. “Does that gadget’s data tell you what

kind

of ships those are?”

“No, but it—”

“Didn’t think so. Our radar can

identify

those ships— PACER SKY’s

printout just gives a position and velocity readout,” Blanchard said. “Without

ISAR identification data, we could only report those ships as a

possible

hostile, and that’s only based

on their formation, not their type.” She referred to a sheaf of computer

printouts he had received from the RC-135’s intensive-signal processors. “Here

it is: the largest ship in that string is a probable Hegu-class fast attack

missile craft. What good is satellite intelligence that only gives you half the

story?”

“Because we wouldn’t have to truck

three thousand miles to find out the Chinese are moving a big convoy into

Zamboanga,” Fruntz said.

Blanchard remained unimpressed.

Fruntz continued: “Look at this:

PACER SKY is telling us there might be defensive missile batteries set up on

the eastern shore of Jolo Island or Pata Island, in the middle of the Sulu

Archipelago. See that? That’s the kind of info we need before we drive into the

area.”

“Well, I guess it doesn’t make that

much difference, because we’re

still

going to drive into that area,” Blanchard said. “If there’s a SAM site or radar

on those islands, they’re not going to turn ’em on until we get closer.”

“It beats getting surprised,” Fruntz

insisted. “I’d rather be ready for a radar to come up than have the bejeezus

scared out of us.”

“I like surprises,” Blanchard said,

but then added quickly, “Sam, you go into these sorties expecting the shit to

hit the fan at any time. Too much information, and you start getting

complacent. You gotta be ready for

anything.

Expect the unexpected ...”

“Radar four reports surface

contact,” one of the radar operators suddenly called out. “Slow velocity ...

now showing ten knots, heading westbound.”

“There’s something that NIRTSat

thing didn’t find,” Blanchard snickered. “No matter how gee-whiz that satellite

is, thirty-minute-old data is still thirty-minute-old data— and it’s garbage to

us.” She turned to the radar operator and said, “I need a designation on that

last contact, Radar. Get on it.”

“Signal two shows primary search

radar on that surface contact,” another operator called out. “Showing C-band,

three-seventy PRF . . . calling it a Rice Screen air-search radar . . .”

“Radar four has an ISAR probable on

that return, calling it a EF4-class destroyer... now picking up escorts,

probably as many as four, within ten miles of EF4.” The ISAR, or Inverse

Synthetic Aperture Radar, mounted in the two prominent fairings on the underside

of the RC-135’s fuselage, could paint a nearly three-dimensional picture of a

ship and, by combining it with a computer data base of thousands of such radar

images, could usually match the radar image with a ship in its computer memory.

The larger the ship, the more accurate the match, and a destroyer-class vessel

was a very large radar return.