Cane (17 page)

Authors: Jean Toomer

“By hearsay,” writes Toomer, echoing W. E. B. Du Bois’s famous description, in

The Souls of Black Folk

, of his own ancestry, “there were in my heredity the following strains: Scotch, Welsh, German, English, French, Dutch, Spanish, with some dark blood. [Let us] assume the dark blood was Negro—or let’s be generous and assume that it was both Negro and Indian. I personally can readily assume this because I cannot feel with certain of my countrymen that all of the others are all right but that Negro is not. Blood is blood…. My body is my body, with an already given and definite racial composition.”

58

After identifying the various racial “strains” in his ethnic heredity, Toomer raises the vital question of genetic ancestry, of race: “Of what race am I? To this question there can be but one true answer—I am of the human race….” Rejecting the one-drop rule (one drop of Negro blood doth forever a Negro make) as well as the reigning preoccupation with racial purity that governed conceptions of race in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century, Toomer claimed a social identity that would inevitably place him at odds with the American mainstream and, in retrospect, make him a pioneering theorist of hybridity, perhaps the first in the African American tradition. Nevertheless, he remained indifferent to the consequences of this position, and quite determined to maintain and justify it, returning to the subject seemingly endlessly in his autobiographical writings. Adopting an unorthodox, progressive, and certainly idealistic position on race that would be the source of some suffering even now in the twenty-first century, he defined himself as an “American, neither black nor white, rejecting these divisions, accepting all people as people.”

59

Toomer’s “racial position” anticipates by

eleven

years a complementary theory of race conceptualized by the Mexican writer and political leader Jose Vasconcelos in

La raza cosmica

(

The Cosmic Race

), published in 1925. In this treatise, Vasconcelos defines the Mexican people as a new race composed of

all

the races of the world. The central claim of

La raza cosmica

is that “the various races of the earth tend to intermix at a gradually increasing pace, and eventually will give rise to a new human type, composed of selections from each of the races already in existence.”

60

According to Vasconcelos, the “new human type” or alternately “the fifth universal race,” the “synthetic race,” “the definitive race,” or the “cosmic race” has its origins in the pre-Mayan legendary civilization of Atlantis.

61

In prose that is marked by a mixture of philosophy, poetry, and mysticism, Vasconcelos asserts that this new cosmic race will be “made up of the genius and the blood of all peoples and, for that reason, more capable of true brotherhood and of a truly universal vision.”

62

It will emerge from the continent of South America, thus fulfilling, according to Vasconcelos, the historic destiny of Latin American people or the “Hispanic race” to bring the races of the world to an advanced state of spiritual development.

63

Based in the “Amazon region,” Vasconcelos calls the capital of this new empire of the spirit “Universopolis,” which will rise on the banks of the Amazon River.

64

One of the “fundamental dogmas of the fifth race” is love as it is expressed within the framework of Christianity which, according to Vasconcelos, “frees and engenders life, because it contains universal, not national, revelation.”

65

Writing as an idealist and a visionary, Vasconcelos argues that we “have all the races and all the aptitudes. The only thing lacking is for true love to organize and set in march the law of History.”

66

Love, then, is the expanding floor upon which will rise “a new race fashioned out of the treasures of all the previous ones: The final race, the cosmic race.”

67

While there is no concrete evidence that Toomer was familiar with the writings of Vasconcelos, there are many affinities between their respective views on race.

68

But it is quite possible that Toomer knew Vasconcelos’s work, given its wide popularity and given Toomer’s sojourns in New Mexico. Toomer and Vasconcelos emerge as prophets of a new order in which the mixed-race person is a pivotal figure, a metaphor or harbinger of a hybrid culture and a fusion of many ethnic and genetic strands. The claims of both are based upon an appeal to the universal, the positive values associated with hybridity and thus a rejection of racial purity, and the belief that racial mixture or

mestizaje

possesses the potential to unify humankind. For Toomer and Vasconcelos, the mixed-race person or the mulatto emerges as a symbol of “cosmic” possibility, and the spiritual resolution of all human conflict rather than as a symbol of human conflict and degeneracy. Gilberto Freye would develop a related theory of “racial democracy” as a hallmark of Brazilian culture in his classic work,

Casa-Grande e Senzaca

,

69

published in 1933. Ferdinand Ortiz would elaborate a similar theory for Cuban culture a few years later in his book, Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar, published in 1940.

70

Vasconcelos’s theory (either directly, or through Toomer) influenced Zora Neale Hurston as well. In “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” Hurston writes, “At certain times, I am no race, I am

me

…. The cosmic Zora emerges.”

71

Toomer arrived at his definition of his own race when most Americans implicitly accepted a “scientific” or biological definition of race, and believed that the world was composed of several distinct racial groups, each with its own history, each with its own place in a racial hierarchy, each with its own special contribution to make to world civilization. W. E. B. Du Bois’s essay, “The Conservation of Races” (1896), theorizes race as a biological or natural concept, but rejects a racial hierarchy, assigning to the Negro a positive value and function among the world’s races: “We are that people whose subtle sense of song has given America its only American music, its only American fairy tales, its only touch of pathos and humor amid its mad money-getting plutocracy.”

72

He would later dismiss “The Conservation of Races” as an instance of “youthful effusion.”

73

In

Dusk of Dawn

(1940), Du Bois revisited the question of race, abandoning the biological or scientific concept of race: “Perhaps it is wrong to speak of it at all as ‘a concept’ rather than as a group of contradictory forces, facts and tendencies.”

74

In this final definition, Du Bois theorized race as a social construct. In doing so, he prepared the ground for a subsequent generation of scholars—Kwame Anthony Appiah, Jacqueline Nassy Brown, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Paul Gilroy, Stuart Hall, Patricia Williams—who would build upon Du Bois’s insight, and theorize race as a social construction or floating signifier. In Du Bois’s writing, we witness the evolution of race from a biological concept to a discursive concept. But unlike Toomer, Du Bois heartily embraced a Negro social and cultural identity, never using its constructed nature as an excuse to “transcend” it; rather to de-biologize or de-essentialize it.

Toomer observed that “it is even more difficult to determine the nature of a man; so most of us are even more content to have a label for him.”

75

In an era when the views of such white supremacists as Lothrop Stoddard and Earnest Cox were in the ascendancy and referenced even in such fictional works as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s

The Great Gatsby

, Toomer proclaimed that in “my body were many bloods, some dark blood, all blended in the fire of six or more generations. I was, then, either a new type of man or the very oldest. In any case I was inescapably myself…. As for myself, I would live my life as far as possible on the basis of what was true for me.”

76

While Toomer’s metaphor of “bloods” recalls a biological conception of race, the direction of his thinking is toward a discursive concept of race. Toomer developed the following plan for its use in the protean, contested world of social relations: “To my real friends of both groups, I would, at the right time, voluntarily define my position. As for people at large, naturally I would go my way and say nothing unless the question was raised. If raised, I would meet it squarely, going into as much detail as seemed desirable for the occasion. Or again, if it was not the person’s business I would either tell him nothing or the first nonsense that came into my head.”

77

It would be left to him, not to others, to define and to determine his location in the social world, or so he imagined. Toomer would soon come to realize the limitations of his own power to shape the manner in which he would be perceived and defined by others, notwithstanding the appeal of his person and personality, and his great confidence in his ability to explain and to rationalize himself.

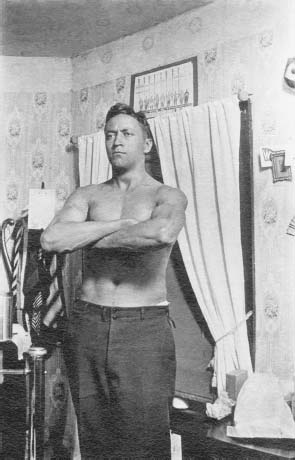

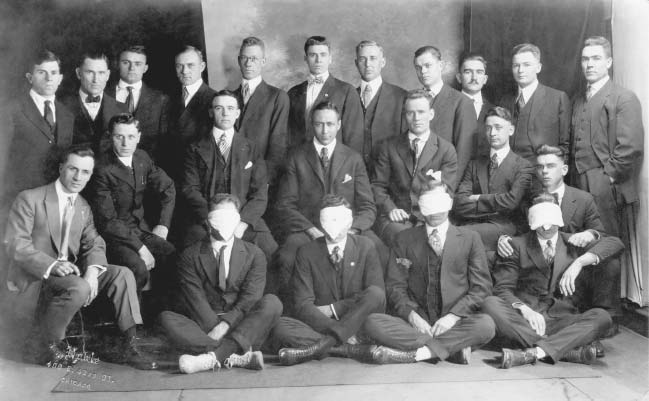

After graduating from Dunbar High School in January 1914, Toomer matriculated at six colleges and universities between 1914 and 1918, but failed to earn a degree. He attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and the Massachusetts College of Agriculture to pursue his interests in scientific agriculture. No longer interested in becoming a farmer, he pursued his new passion for exercise and bodybuilding at the American College of Physical Training in Chicago in January 1916. Toomer remained in Chicago through the fall and enrolled in courses that introduced him to atheism and socialism at the University of Chicago. In the spring of 1917 he decided to travel to New York, and there enrolled in summer school at New York University and the City College of New York where, respectively, he took a course in sociology and history. “Opposed to war but attracted to soldiering,” wrote Kerman and Eldridge, Toomer volunteered for the army, but he was “classified as physically unfit ‘because of bad eyes and a hernia gotten in a basketball game.’”

78

As we reveal in “Jean Toomer’s Racial Self-Identifcation,” Toomer registered as a Negro.

In 1918, Toomer returned to the Midwest, where he held a series of odd jobs, including becoming a car salesman at a Ford dealership in Chicago. During this second period in Chicago, he wrote “Bona and Paul,” his first short story, in which he explored questions of passing and mixed-race identity, a powerful work that would eventually find its way into the second section of

Cane.

In February 1918, Toomer accepted an appointment in Milwaukee as a substitute physical education director, and continued his readings in literature, especially the works of George Bernard Shaw.

79

Returning briefly to Washington, D.C., Toomer set out again for New York where he worked as a clerk with the grocery firm Acker, Merrall, and Condit Company. While in New York, his reading expanded to include Ibsen, Santayana, and Goethe; he attended meetings of radicals and the literati at the Rand School, as well as lectures by Alfred Kreymborg, who, a decade later, would describe Toomer as “one of the finest artists among the dark race, if not the finest.”

80

In the spring of 1919, he left Manhattan to vacation in the resort town of Ellenville, New York. Indigent though somewhat rested, he then returned to Washington in the fall, where he was confronted by the condemnations of his grandfather who was far from pleased with his grandson’s vagabond existence.

College photograph of Jean Toomer, bare-chested with arms folded, 1916. Jean Toomer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke and Rare Book Manuscript Library.

Group portrait with Toomer at center ( four men in front blindfolded), from the Lunkentus Class of 1917 yearbook (American College of Physical Education). Jean Toomer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke and Rare Book Manuscript Library.