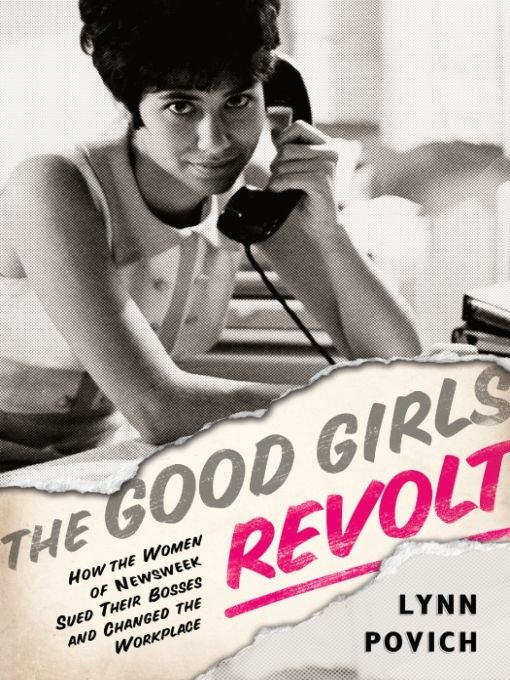

The Good Girls Revolt

Read The Good Girls Revolt Online

Authors: Lynn Povich

Tags: #Gender Studies, #Political Ideologies, #Social Science, #Civil Rights, #Sociology, #General, #Discrimination & Race Relations, #Conservatism & Liberalism, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Political Science, #Women's Studies, #Journalism, #Media Studies

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1 - “Editors File Story; Girls File Complaint”

CHAPTER 2 - “A Newsmagazine Tradition”

CHAPTER 5 - “You Gotta Take Off Your White Gloves, Ladies”

CHAPTER 7 - Mad Men: The Boys Fight Back

CHAPTER 8 - The Steel Magnolia

CHAPTER 10 - The Barricades Fell

CHAPTER 11 - Passing the Torch

For Steve, Sarah, and Ned

and for the

Newsweek

women

PROLOGUE

WHAT WAS THE PROBLEM?

J

ESSICA BENNETT GREW UP in the era of Girl Power. It was the 1980s, when young women were told there was no limit to what they could accomplish. The daughter of a Seattle attorney, Jessica regularly attended Take Your Daughter to Work Day with her dad and was the academic star in her family, excelling over her younger brothers and male peers. In high school, she was a member of Junior Statesmen of America, a principal in the school orchestra, and a varsity soccer player. Jessica was accepted to the University of Southern California, her first choice, but transferred after freshman year to Boston University because it had a stronger journalism program. When the

Boston Globe

offered a single internship to a BU student, she was the recipient.

Then Jessica got a job at

Newsweek

and suddenly encountered obstacles she couldn’t explain. She had started as an intern on the magazine in January 2006 and was about to be hired when three guys showed up for summer internships. At the end of the summer, the men were offered jobs but Jessica wasn’t, even though she was given one of their stories to rewrite. Despite the fact that she was writing three times a week on

Newsweek’

s website, her internship kept getting extended. Even after she was hired in January 2007, Jessica had to battle to get her articles published, while guys with the same or less experience were getting better assignments and faster promotions. “Initially I didn’t identify it as a gender issue,” she recalled. “But several of us women had been feeling like we weren’t doing a good job or accomplishing what we wanted to. We didn’t feel like we were being heard.”

Being female was not something that ever held Jessica back. “I was used to getting everything I wanted and working hard for it,” said the twenty-eight-year-old writer at

Newsweek.com

, “so my feeling was, why do I need feminism? Why do I need to take a women’s studies course? And, of course, there was the stereotype of the feminist—the angry, man-hating, granola-crunching, combat-boot-wearing woman. I don’t know that I consciously thought that, but I think a lot of young women do. I went to public school in the inner city, so issues of racial justice were more interesting to me than gender because, frankly, gender wasn’t really an issue.”

Her best friend at

Newsweek,

Jesse Ellison, was also frustrated. She had recently discovered that the guy who replaced her in her previous job was given a significantly higher salary. She was doing well as the number two to the editor of Scope, the opening section of the magazine that featured inside scoops and breaking news. But that summer, a half-dozen college-age “dudes” had come in as summer interns and suddenly the department turned into a frat house. Guys were high-fiving, turning the TV from CNN to ESPN, constantly invading her cubicle, and asking her, as if she were their mother, whether they should microwave their lunches. They were also getting assigned stories while she had to pitch all her ideas. Since a new boss had taken over, Jesse felt as if she had been demoted. She didn’t know what to do.

Jesse, thirty, sought the advice of a trusted editor who had been a mentor to her. He told her, “You’re senior to them—shame them.” Then he said, “The problem is that you’re so pretty you need to figure out a way to use your sexuality to your advantage,” she recalled, still incredulous about the remark. “Even though I think he was just being an idiot for saying this—because he had really fought for me—hearing that changed my perception of the previous six months. I was like, ‘Wait a minute! Were you being an advocate for me because you think I’m pretty and you want me in your office? And, more important, is this what other people in the office think? Not that I’m actually talented, but this is about something else?’ It really screwed with my head.”

Jesse had grown up in a conservative town outside Portland, Maine. Her mother, a former hippie who was divorced, had started a small baby-accessories business. During the Clarence Thomas Supreme Court hearings, Jesse was the only one in her eighth-grade class to support Anita Hill. She went to a coed boarding school, where she was valedictorian of her class, and then to Barnard, an all-women’s college, where she graduated cum laude. She, too, never took a women’s studies course. “I just felt like I didn’t need it,” she said. “Feminism was a given—it was Barnard!” After a brief job at a nonprofit, she enrolled part-time in Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. She also got an internship on the foreign language editions of

Newsweek

and was hired full-time when she graduated with her master’s degree in June 2008. But now, a year later, she, too, was struggling to move ahead at

Newsweek

. What was the problem?

“It wasn’t like I believed that sexism

didn’t

exist,” said Jesse. “It was just that it didn’t occur to me that what was happening at work was sexism. Maybe it’s because we are a highly individualized culture now and I had always done really well. So I just assumed that everything that was happening was on the basis of merit. I grew up reading

Newsweek

and I had tremendous respect for it. I felt like, I’m in this world of real thinkers and writers and I have to prove myself. The fact that I wasn’t being given assignments was simply an indication that they didn’t think I was good enough yet. It didn’t occur to me that it was about anything else. For the first time in my life, I was feeling inadequate and insecure.”

Jessica Bennett felt the same way. “Maybe it’s a female tendency to turn inward and blame yourself, but I never thought about sexism,” she said. “We had gotten to the workforce and then something suddenly changed and we didn’t know what it was. After all, we had always accomplished everything we had set out to do, so naturally we would think

we

were doing something wrong—not that there

was

something wrong. It was us, not it.”

What

was

the problem? After all, women composed nearly 40 percent of the

Newsweek

masthead in 2009. It wasn’t like the old days, when there was a ghetto of women in the research department from which they couldn’t get promoted. In fact, there were no longer researchers on the magazine, except in the library. Young editorial employees now started as researcher-reporters. There were women writers at

Newsweek,

several female columnists and senior editors, and at least two women in top management. Ann McDaniel, a former

Newsweek

reporter and top editor, was now the managing director of the magazine in charge of both the business and editorial sides—a first. So it couldn’t be that old thing called discrimination that was inhibiting their progress. The fight for equality had been won. Women could do anything now at

Newsweek

and elsewhere. Hadn’t Maria Shriver’s report on American women just come out in October 2009, declaring, “The battle of the sexes is over”?

Jesse and Jessica stewed about the situation, discussing it with other

Newsweek

women and friends outside the magazine, who, it turned out, were also feeling discouraged in their careers. “It felt so good just talking to each other,” recalled Jesse. “It was like, ‘Oh my God, I’m so sick of feeling silent and scared. It’s not fair and we should say something.’ That impulse was great; knowing that ‘I’m not alone’ was empowering.”

One day Jen Molina, a

Newsweek

video producer, was talking about the magazine’s “old boys club” to Tony Skaggs, a veteran researcher in the library. Tony informed her that many years before, the women at

Newsweek

had sued the magazine’s management on the grounds of sex discrimination. Jen was shocked. She had no idea this had happened—and at her own magazine. She told Jessica, who told Jesse, and the two friends began investigating. Jessica immediately Googled “

Newsweek

lawsuit” and “women sue

Newsweek

” but she couldn’t find any reference online. “Funny,” she remarked, “we’re trained in digital journalism, so we think if it’s not on Google, it doesn’t exist.”

A few weeks later, Tony walked into Jessica’s office with a worn copy of Susan Brownmiller’s vivid chronicle of the women’s movement,

In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution.

A crumpled Post-it note marked the chapter mentioning a lawsuit at

Newsweek

in 1970, almost forty years earlier. “I just remember sitting at my desk reading it,” she said, “and every two sentences saying, ‘Holy shit,’ because I couldn’t believe this had happened and I didn’t know about it! So I instant-messaged Jesse and said, ‘You have to get over here and read this.’ Why didn’t we know this? Why has this died? And why was there only one person in the research department who had to get this book for us to let us know about it?”

When they read about the case, it all seemed so familiar. “We realized we were far from the first to feel discrimination,” said Jesse. “So much of the language and culture was still the same. It helped drive home the fact that it was still the same place, the same institutional knowledge, the same

Newsweek.

”

This happened in the fall of 2009, just as a scandal at CBS’s

Late Show with David Letterman

was making headlines. Joe Halderman, a CBS News producer who was living with one of Letterman’s assistants, had found her diary revealing her ongoing affair with her boss. Halderman threatened to expose the relationship if Letterman didn’t give him $2 million. On October 1, Letterman confessed—on air—that yes, “I have had sex with women who work for me on this show.” That same month, ESPN analyst Steve Phillips, a former general manager for the New York Mets baseball team, was fired from the sports network after admitting that he had an affair with a twenty-two-year-old production assistant. In November, editor Sandra Guzman, who was fired from the

New York Post,

filed a complaint against the newspaper and its editor-in-chief alleging “unlawful employment practices and retaliation” as well as sexual harassment and a hostile work environment. (The case is pending in Manhattan federal court.)

The Letterman scandal infuriated Sarah Ball, a twenty-three-year-old Culture reporter at

Newsweek,

particularly after she read an article by a former Letterman writer. “I was galvanized by Nell Scovell’s story on

VanityFair.com

,” recalled Sarah, who cited the beginning of the piece by heart: “At this moment, there are more females serving on the United States Supreme Court than there are writing for

Late Show with David Letterman, The Jay Leno Show,

and

The Tonight Show with Conan O’Brien

combined. Out of the fifty or so comedy writers working on these programs, exactly zero are women. It would be funny if it weren’t true.” Sarah told her editor, Marc Peyser, about the piece and in the course of the conversation, Peyser suggested a story on young women in the workforce, pegged to the scandals. “He was really into it,” Sarah recalled. “He kept saying, ‘This could be a cover, this could be a cover.’” Sarah, who had seen the Brownmiller book, immediately told Jessica and Jesse about Peyser’s interest. The three women went back into his office and pitched a story combining the old and new elements. “It was perfect,” said Jesse. “It was bigger than us, we had our own narrative that we felt was important, and there was the forthcoming fortieth anniversary of the lawsuit in March.”