Cape Cod (2 page)

But the earth still turns, too. The light falls exactly as it did when the Pilgrims walked the shore in spring or fall. The summer people come every Fourth of July. The tides rise and fall and sometimes confuse the pilot whales that stray too close to shore.

In the mild winter of 2011-2012, Cape Cod beaches saw several huge dolphin strandings. Why were the dolphins, close relatives of the creatures that appear in the first scene of this book, hurling themselves onto the beaches? Was it disease, global warming, or just another of nature’s relentless and sometimes heartless cycles? No one knows.

The generations may come and go, but on Cape Cod, the deepest mysteries remain, and so do the deepest memories.

William Martin

March 2012

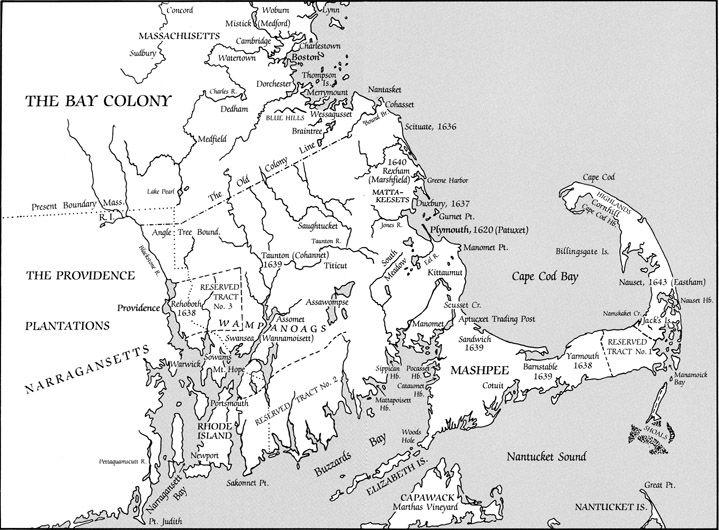

A.D. 1000

Each year the whales went to the great bay. They followed the cold current south from seas where the ice never melted, south along coastlines of rock, past rivers and inlets, to the great bay that forever brimmed with life. Sometimes they stayed through a single tide, sometimes from one full moon to the next, and sometimes, for reasons that only the sea understood, the whales never left the great bay

.

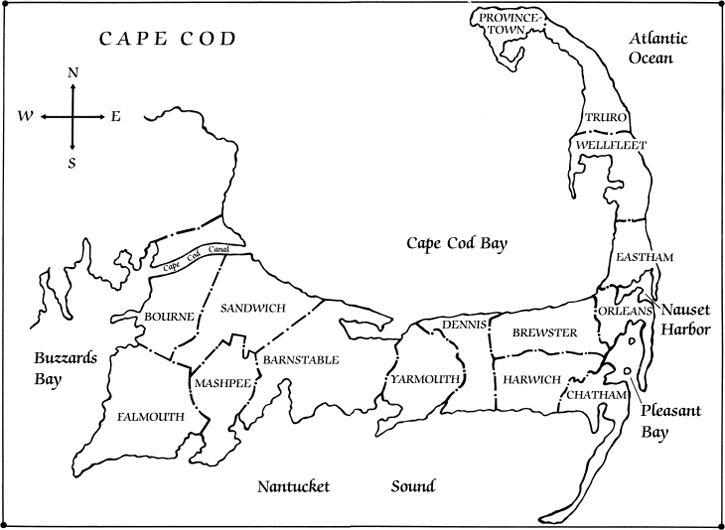

The season was changing on the day that the old bull led his herd round the sand hook that formed the eastern edge of the bay

.

It had come time for them to fill their bellies and begin the journey to the breeding ground. The old bull did not need the weakening of the sunlight or the cooling of the waters to know this. He knew it because his ancestors had known it, because it was bred into him, in his backbone and his blood. And he knew that in the great bay, his herd had always fed well

.

So he sent out sounds that spread through the water and came echoing back, allowing him to see without sight, to know the depth of the water and the slope of the beach, to sense the movement of a single fish at the bottom of the sea or the massing of a giant school a mile away

.

And that was what the old bull sensed now

.

He turned toward the school, and his herd turned with him. A hundred whales swam in his wake, linked by color and motion in a graceful seaborne dance, by the simple rule of survival to the fish before them, and by the deeper call of loyalty to the herd, their kin, and the old bull himself

.

Then the sea was lit by a great flash. The fish felt the coming of the whales, and like a single frightened creature, they darted away. First east, then west, then south toward the shallows they went, and the sunlight flashed again and again on their silver sides

.

The dance of the whales rose into a great black-backed wave and rolled, steady and certain, toward the shoal of fish. Soon the stronger fish were swimming over the weaker and splattering across the surface to escape. It did them no good. The wave struck, churned through them, and pounded on, leaving a bloody wake in which the gulls came to feast, while on the shore, other creatures watched and waited

.

The old bull filled his belly, and as always in the great bay, the herd fed well. But their hunger was as endless as the sea, and their wave rolled on to the shallows where the last of the fish had fled. Black bodies lunged and whirled in the reddening water. Flashes of panic grew smaller and dimmer. Then came a flash that seemed no more than a moment of moonlight. The old bull turned to chase it, and the movement of his flukes brought the sand swirling from the bottom

.

He had led the herd too close to shore and the tide was running out. In the rising turbulence, he could see almost nothing, so he made his sounds, listened for the echoes, and sought to lead the herd toward safety

.

But something in the sea or the stars or his own head had betrayed the old bull. He followed his sounds, because that was what he had always done, and swam straight out of the water. The herd followed him, because that was what they had always done, and the black-backed wave broke on a beach between two creeks

.

Still something told the old bull that he was going in the right direction. He pounded his flukes to drive himself into one of the creeks. But he did no more than send up great splashes and dig himself deeper into the eelgrass that rimmed the creek

.

All around him, black bodies flopped uselessly in the shallows. The sun quickly began to dry their skin. And their own great weight began to crush them

.

The old bull heard feeble warning cries, louder pain cries. He felt the feet of a gull prancing on his back. Then new cries, patterned and high-pitched, frightened the gull into the air

.

From the line of trees above the beach came strange creatures, moving fast on long legs. They wore skins and furs. They grew hair on their faces. They carried axes that flashed like sunlight

.

They were men. And they swarmed among the herd without fear, and drove their axes into the heads of the whales, and brought blood and death cries. And the biggest of them all raised his axe and came toward the old bull

.

But before the axe struck, an arrow pierced the man’s neck and came out the other side. Blood and gurgling sounds flowed from his mouth. His eyes opened wide and the axe dropped from his hand

.

Now men with painted faces came screaming from the woods. The old bull felt the clashing of the fight and heard sounds of fury unlike any he had known in the sea. Rage swirled around him, stone against iron, arrow against axe, bearded man against painted man. And with his last strength, he tried to escape

.

He pounded his flukes but could do no more than roll onto his side, his great bulk burying the axe in the marsh mud beneath him

.

Then a bearded man beheaded the painted chieftain and his painted followers fled. The victor lifted the head by the hair and flung it into the sea, but the other bearded men did not celebrate their victory. Instead, they ran off in fear

.

For some time, the old bull lay dying on the beach between the creeks. Then the bearded men appeared once more, this time with a woman of their kind. Their axes flashed like the sides of panicked fish, and like the fish, they were fleeing. But the woman stopped and looked at the old bull. She made angry sounds. She picked up a boulder and raised it over his head…

.

June 30, 1990

One of them had seen every year of the century, the other a full three score and ten. One had trouble sleeping. The other wondered where the years had gone. Neither ever awoke without a new pain somewhere or an old pain somewhere else. And neither could drink much anymore, or he’d spend the night at the toilet, pissing out ineffectual little dribbles that wouldn’t even make a satisfying sound.

But in these things, they were like old men everywhere. Other things bound them like brothers.

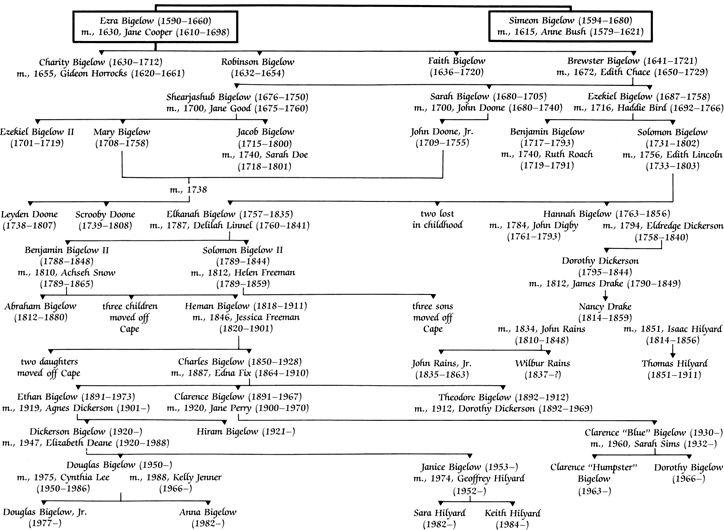

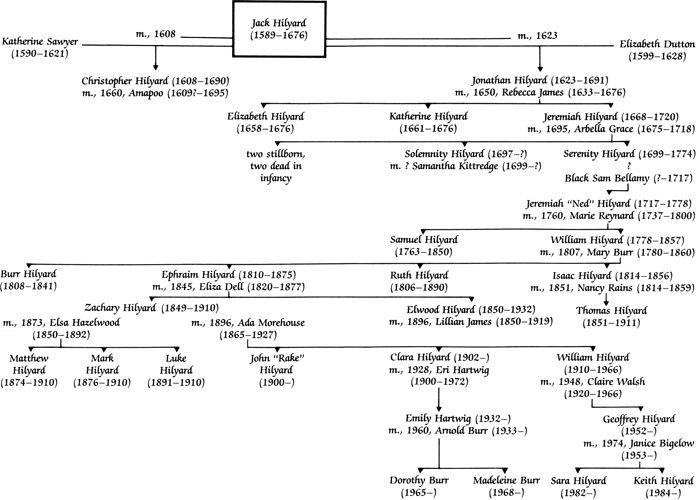

Both were descended from the

Mayflower

Pilgrims. One was grandfather, the other great-uncle, to the same two children. They walked on the beach between the creeks because each owned half of it. And they had detested each other since the administration of John F. Kennedy.

Rake Hilyard walked at dawn. The world was changing quickly, but he found perspective on the beach. Seasons passed, birds migrated, and tides flowed according to laws laid down long before the foolishness began. In the dunes, Indian shell heaps gave evidence of the first men. In the marsh mud, the bones of ancient pilot whales told of the first standings. Even the sea-smoothed boulders on the tideflats recalled the glacier that left them. And all of it made a ninety-year-old man feel a little younger.

Dickerson Bigelow did not come out as regularly. But after the heart attack, his doctor had told him to walk more, and on the beach, he could work even as he walked. If the tide was low, Dickerson walked on the flats, studied the island from a distance, and imagined what the last development of his life would look like. When the tide was high, he simply walked, his eyes fixed on the sand between his toes, his soul coveting the land on the Hilyard side, his brain scheming to get it.

At high tide on this summer morning, the beach was no more than a twenty-foot strand from wrack line to dune grass, which meant the old men could not avoid each other. But neither would turn back. They had been trespassing on each other’s beaches for decades, like warships showing their flags in foreign straits. So they ran out their guns and steamed on.

Dickerson fired first. “Mornin’, you old bastard.”

“What’s good about it, you son of a bitch?”

“We’re alive and can walk the beach. How’s that?”

“If it was up to you, only

one

of us’d be alive. Then

you’d

fill the creeks and hot-top the beach.”

Dickerson Bigelow laughed and ran a hand through the beard that fringed his face. He shaved his upper lip, in the style of an old shipmaster, so that whenever he bought property or petitioned for a permit, he would seem to have sprung from the Cape Cod sand itself, a modern man with the shrewd yet upright soul of a Yankee seafarer.

Next to him, Rake looked like the original go-to-hell dory fisherman—leathery face, dirty cap, dirtier deck shoes, and flannel shirt stuffed into trousers so dirty you could chop them up and use them for chum.

Rake glanced at Dickerson’s bony bare feet, the same color as the sand, at the gray trousers rolled up to the calves, the windbreaker draped over the barrel chest, and the knot of the striped tie. “Men don’t wear ties to the beach ’less they come on business.”

“Our families have quite a resource here, Rake.”

“Answer’s no.”

“Magnificent spot.” Dickerson stepped to the top of the dune and looked around.

“Mind the dune grass. That’s Hilyard property. Don’t want it blowin’ away.”

“It

is

blowin’ away. The whole

Cape’s

blowin’ away, washin’ away, every day. Time to sell, ’fore any more of it goes.”