Carla Kelly

Authors: Miss Chartley's Guided Tour

Miss Chartley’s Guided

Tour

by

Carla Kelly

SMASHWORDS

EDITION

* * * * *

PUBLISHED BY:

Camel Press on

Smashwords

Miss Chartley’s Guided

Tour

Copyright © 2013 Carla

Kelly

* * * *

PO Box 70515

Seattle, WA 98127

For more information go to:

www.camelpress.com

www.carlakellyauthor.com

All rights reserved. No part of this

book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names,

characters, places, brands, media, and incidents are either the

product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously.

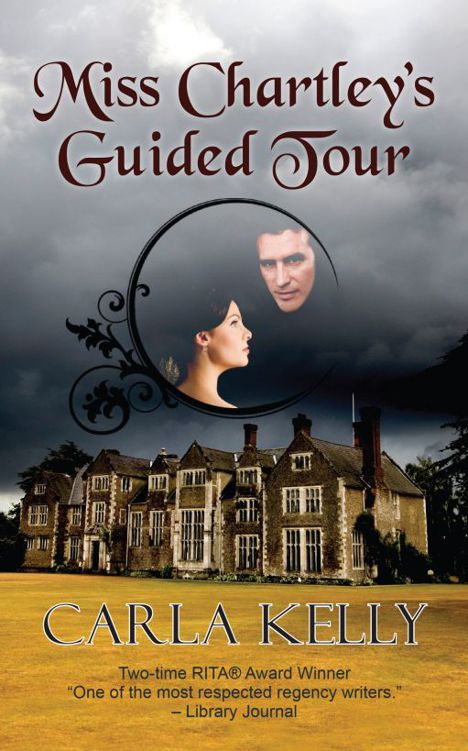

Cover design by Sabrina Sun

Miss Chartley’s Guided Tour

Copyright © 1989, 2013 by Carla

Kelly

ISBN: 978-1-60381-913-8 (Trade

Paper)

ISBN: 978-1-60381-914-5 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number:

2013933744

Produced in the United States of

America

Smashwords Edition License

Notes

enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to

other people. If you would like to share this book with another

person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you

share it with. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it,

or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return

it to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for

respecting the author's work.

* * * *

For Rosalind Barrow,

my-sister-in-law

* * * *

If he were a

wagering man, he would have bet houses, lands, horses, and hounds

that he was the first of his line to ride to his wedding in a hired

conveyance.

The thought

afforded no pleasure, only a deep washing of shame that flooded his

body from face to toes. He closed his eyes against it, only to see

himself again as though it were early morning, stumbling into the

alley off St. James Square and falling to his knees on the

cobblestones, overcome by the enormity of what had

happened.

“

My

God, what have I done?”

It was the first

thing he had said aloud in hours, and his words made him jump and

then grasp the hanging strap in the hackney. He gripped it tight,

retracing in his mind the long walk back to his own flat on Curzon

Street, well-wrapped in his opera cloak, head down, praying no one

would know him, or speak to him, or wish him

congratulations.

He opened his

eyes and sobbed out loud, seeing again the pile of bloody clothes

he had ripped from his body as if they had burned him, standing

naked in front of his mirror and not having the courage to look

himself in the eye.

The cold that

covered him then, covered him still. He was still shivering, still

trembling like an old man with palsy. After he had dressed himself

he had tried and tried to pick up the little wedding ring on his

bureau. It had taken both hands, and then he had dropped it twice

before seeing it into his pocket.

The clothes

jumbled about him on the floor he wrapped in his opera cloak and

carried down the stairs and into the alley. A quiet walk behind the

row of flats and then the bundle was stuffed deep into someone

else’s ashcan.

There was no time

to speak for his curricle from the stables. He had hailed a hackney

and directed the Irishman sitting on the box to St. Alphonse on

Wadlington Lane, his fiancée’s special choice because she loved the

stained-glass windows and the choir screen.

The driver looked

at him carefully, and his heart dropped to his shoes and stayed

there. “Are ye all right, sor?”

He had nodded,

too devastated to speak. If I open my mouth, I will tell him

everything, he thought. No one must ever know.

The journey that

he wished would take years was over in a matter of minutes. The

hackney stopped and the driver sprang from the box and stood by the

door, hand on the latch. “St. Alphonse, sor,” he said.

“

Oh,

drive on, please. Just a little farther.”

After another

careful look and a shake of his head, the driver returned to the

box and clucked to his horse. When they were beyond the church, he

slowed again, and rapped on the roof.

He had no idea

how much money he gave the driver. The man sucked in his breath and

bowed, so it must have been more than patrons usually flicked his

way. He turned to go, and the man grasped his arm. Again the chills

traveled the length of his body.

“

You’ll not be calling the constable and telling him I robbed

you, now, will you, sor?”

He waved the

driver away and started back toward St. Alphonse. The clock in a

tower several blocks distant chimed twice; he was already half an

hour late. He wiped the sweat from his face, unmindful of the cold

wind that blew off the river. At least all the wedding guests would

be inside. He would be far to the front, next to the altar, and if

he looked a little pale, his friends and relatives would put it

down to wedding jitters.

He forced himself

to hurry. His best man had never been distinguished for his patient

temperament and was probably even now wearing a rut in the carpet.

And his fiancée?

He broke into a

run which ended on the bottom steps leading to the massive front

door of St. Alphonse’s Church. Already a crowd had assembled, a

collection of children and poor people from the neighborhood, who

knew that the gentry inside were inclined to be generous when they

came out after a wedding. And failing that, there were pockets to

pick.

But the people on

the steps were talking among themselves, casting a glance at the

church now and then, and laughing behind their hands. Some were

already beginning to move away.

He mounted the

steps, two at a time, and stood by the entrance with another crowd

of more brazen folk, bits of London chaff blown there by news of a

wedding. He stood next to a man who balanced on one leg and a peg,

a man who nudged him and winked.

“

I

disremember when ever I saw

this

happen before. And what a

crime, I say. Look there at that pretty little lady.”

“

Yes,

look,” chimed in the woman on the other side of Peg-leg. “You

should have seen her skip up the steps. And such a smile on her

face! You could have lit lighthouse lamps from that

smile.”

He could only

groan inwardly as another great tide of shame washed over

him.

Peg-leg shook his

head. “And now her face is whiter than her dress. There’s one

gentleman ducking and running in this city who ought to be pulled

up sharp-like. See her there?”

He looked where

Peg-leg pointed. The doors were open and there she sat in the

vestry of the church, flowers drooping out of her hand, her face a

study in shock. Her brother was speaking to her, kneeling by her,

his hand on her back. She drew away from him. When her father

squared his shoulders and started up the aisle toward the altar to

make an announcement, she burst into tears, helpless tears that he

knew would ring in his mind and soul for the rest of his

life.

The clock in the

tower chimed the half-hour. From habit he pulled out his pocket

watch and clicked it open. Two-thirty. He snapped it shut and

shoved it back in his pocket, feeling as he did so the wedding

ring.

He couldn’t leave

London fast enough.

1

When the coachman

blew on his yard of tin and signaled their approach to King

Richard’s Rest, Omega Chartley pulled her mother’s watch from her

reticule, snapped it open, and examined it. They were precisely on

time. The thought pleased her, as all perfect things did, and she

smiled to herself.

The loudly

dressed fribble sitting opposite her mistook her smile for approval

of himself. He sat a little straighter and tugged at his wilted

shirt points, smiling back and revealing a mouthful of improbable

porcelain teeth.

Omega snapped the

watch shut with a click that made the vicar next to her sit up and

peer around in fuddled surprise. She fixed the forward young man

across from her with the same quelling stare that had reduced many

an unprepared student of English grammar to visible idiocy. The man

gulped and looked away as the color drained rapidly from his

face.

It was high time

she squelched his pretensions. Earlier that morning, when she was

dozing off as a result of her sleepless night in the last inn,

someone (she suspected the man with porcelain teeth) had prodded

her feet in a scarcely gentlemanlike manner. It would never have

done to call attention to the matter; how nice that she could put

him in his place now.

“

So

the rain has finally stopped,” remarked the clergyman on her left

as he pulled himself awake and tried valiantly to fill in the awful

silence caused by Omega’s set-down.

She returned some

suitable, if vague, answer, and looked out the window. The rain had

stopped, but there was no lifting of the gray covering that had

settled over the gentle hills and valleys. All was gray. It was not

a propitious beginning to her holiday.

Throughout

Plymouth’s dreary winter and spring, when each day was done and she

had corrected papers until her eyes burned, she had treated herself

each night to a few moments with

Rochester’s Guidebook of

England for Ladies.

By the sputter and stink of the work

candles that Miss Haversham grudgingly provided for her teachers,

Omega Chartley had plotted out the journey that would take her from

Plymouth on holiday.

At first the

holiday had no plans beyond an excursion to Stonehenge on the

Plains of Salisbury (“Entirely suitable for ladies not easily

exercised by thoughts of druidical rites,” according to the

Guidebook

),

and

then beyond to the Cotswolds and back again. When, in early spring,

a letter had arrived from St. Elizabeth’s in Durham with a coveted

contract to teach English grammar in the wilds of north England,

the holiday turned into a move.

Other than a

brief trip to Amphney St. Peter for Alpha’s wedding, she had not

left Plymouth in eight years. Omega could claim no attachment to

the damp seacoast town other than the fact that it was far removed

from anyone she once knew. Miss Haversham’s Academy for Young

Ladies would not bring her face-to-face with any bad

memories.

For several

years, Alpha Chartley had tried in vain to draw her from Plymouth

to Amphney St. Peter. Omega would have none of it; she had chosen

her exile and there she would remain. And so she would have, had

not the letter come from her own former teacher, advising her of

the vacancy and requesting that she apply for it.

And so Omega had

applied. She was weary of the gray ocean. She could hide in Durham

as well as Plymouth and teach mill owners’ daughters instead of the

offspring of sea captains. The money was better too. She was on the

shady side of twenty-six, and needed to think about her

future.

But there was the

present to contend with now, and the clergyman who bumped her as he

gathered together his belongings.

“

Pardon, miss, pardon,” he said, his face as red as Mr.

Porcelain Teeth’s waistcoat.

Omega smiled to

reassure him, and made herself small in her corner of the mail

coach. She sighed inwardly and wondered if the time would ever come

when she would feel at ease traveling on the common

stage.

The pretentious

young man left the coach as soon as it rolled to a stop, not

glancing her way again. The vicar followed and then stood by to

give her a hand out.

As she was

bending out of the coach and reaching for his hand, a traveling

coach rolled into the innyard and dashed past the Royal Mail,

spattering the vicar with mud. Omega leaned back inside to avoid

the mud, but she was sure she could hear people laughing inside the

closed coach.