Carter Beats the Devil (57 page)

There was so much life here in the spirit world. One could hardly keep track. He reached into his pockets and found the numbskull, which he would eventually return to James—it would bring back old, amusing times for him and Tom. He also located cash for a taxicab. When he recovered his expense journal, he would write “Rec’d from Agent Samuelson,

twelve dollars

” in the asset column, which pleased him to no end.

He looked toward the city of Oakland, to what he could see of the deepening orange skyline, from the new homes at Adams Point to the ferryboats, from the dark lake—there, the necklace of lights flicked on, just now!—to the underfed downtown, with its empty offices and buildings constructed awkwardly and cheaply due to graft and ambition. As a taxi arrived for him, he regarded the tall and straight Tribune Tower, pointed at it, made a dirigible in his mind, and placed it there.

Across the bay, the rain caught San Francisco—which pretended it had no rain except when picturesque—by surprise. At the end of the workday, people bought the morning

Examiner

only for its ability to keep away the wetness.

Griffin stood on the steps of the public library, which had closed moments before he got there. Finally, Olive White—who had a mauve umbrella today, one that matched her galoshes—came out. She was, to say the least, stunned to see him.

“Mr. Griffin, you’re soaked through.”

“It’s nothing. Look, Olive, I’ve been assigned to Albuquerque. I have to leave right now.”

“Oh, Mr. Griffin!” She covered her mouth as if he’d said he’d been shot.

“No, it’s okay. But I have something I need to keep researching, and I don’t know if I can do it from there. If—”

“Anything you say. Anything.”

He unwrapped the wine bottle and showed it to her. She held it to the rainy afternoon sky, and he looked up and down the street—no one seemed to be watching them.

“I’ve never seen this brand before,” adding, as she colored, “I have a prescription from my doctor for my high blood—”

“Okay, yeah, look, just keep your eyes open. If you see anything like this, let me know.”

“May I keep the bottle?”

“Evidence. Sorry.”

“I wish I could commit this label to memory. I’d sketch it if that were possible, but . . . it’s so odd.”

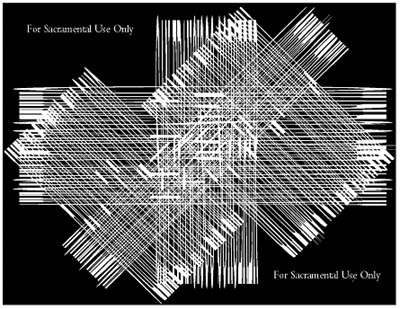

The graphic to which she alluded was almost impossible to describe or reproduce; a clever bootlegger always wanted such a logo. This one was as follows:

Finally, Griffin had to leave. He put the bottle back in his satchel. He offered Olive his hand, and she shook it. She didn’t seem to want to let go, and when she spoke, it was to ask if she could have a hug. Griffin nodded. She wrapped her arms around him for a moment, and he gave her a peck on the cheek.

Then, because duty called him, Jack Griffin turned up his collar, and walked into the rainstorm. Olive watched him from under her umbrella, and even though he didn’t look back, she kept one hand up, preparing to wave, until he was lost from her sight.

A week later, Carter drove his Pierce-Arrow onto the grounds of Arbor Villa. He wasn’t using the BMW much, as his ribs had been taped and his wrists were sprained. He limped to the front door slowly, even more slowly than his injuries would allow, as this was a trip he couldn’t believe he was making.

Borax was outside today, in his chair, reading a book. Beside him was a table on which there was a pitcher of lemonade.

“Hey, Charlie,” he called. “How’s tricks?”

Carter didn’t answer. He took the book from Borax’s hands and closed it, and then dropped it on the grass.

Borax drew a heavy sigh. “I’m sorry. I really am.”

“Twenty years ago, I heard a rumor from someone that God told you to be good. Who told me that?”

“Guilty.” He raised his hand. “I ain’t gonna ask for forgiveness, because that’s not yours to grant.”

“I don’t want to forgive you anything. I want the plans to television back.”

Borax fanned himself with his hat. “You gonna tell me how you figured out it was me?”

“I’m not playing.”

Borax’s eyes fixed on an unknowable point among the trees. “You watched Hollis, I figure. And you got friends in the bank business, so you see he’s making twice as much as everyone else. Darn it, I thought no one could trace those transfers back this way. You know some smart guys, Charlie.”

“I want it back.”

“That Hollis is a mover.”

“They drugged me and threw me in the bay, Borax.”

“I feel real bad about this one. It’s eating me down to my guts. But I had the word out, anything that looked fishy that had to do with Harding, bring it right to me. And there it was. Didn’t mean for you to be the middle man.”

“Middle man? Harding gave that to me, not you.”

“Like I say, it’s eating me, Charlie. But it’s too big to leave alone. Just

one investment in the right place could get me straight out of hock. You don’t know what that feels like.”

Carter said nothing. He simply stared at Borax with such ill-contained rage that the older man had to look away.

“Okay, here it is. I look at this as a trade.” Borax folded his arms. “That’s the only way—”

“A trade?”

“Yeah, a trade.”

Carter said, “I know I’m not a financial genius, but wouldn’t a trade involve me

getting

something besides drugged and dropped in the bay?”

“Sure.” He sounded calm when he said it. “I figure it has to be a good trade. You gave me television, whether you meant to or not, and I give you something you like even more.”

Carter looked over his shoulder as if he were looking for what on earth Borax meant. “And?”

“You’ll get it eventually.”

“I’m sorry, are we being metaphorical here? You’re going to give me the gift of going bankrupt in a few more seasons?”

“No . . .”

“Peace of mind? Good health? Tell me if I’m getting warm.”

“Charlie, it ain’t anything like that. I’ll give you a tangible asset. Trust me on this.”

Carter put his hands in his pockets. He stretched to his full height. “Somewhere down the line, you became a bastard.”

. . .

A week after that sorry meeting, Pem Farnsworth was discharged from Cowell Hospital. She had a slight palsy that was expected to clear up as long as she had enough bed rest. She was sent home by special train to Utah. The tab for the train, and for the hospital bill, was picked up by a few men who had attended Philo’s demonstration. When Philo heard this news, he brightened, but only until he found the group had also paid for a second-class ticket for him to leave town.

His failed experiment hadn’t made the front page of any paper, but several recorded it in their local sections. Consensus was that he was a gifted crackpot who had tampered with forces he didn’t quite know how to control. Dr. Talbot, from RCA, was quoted as saying that when the precocious boy learned the rudiments of physics, there might be a place for him at the table. Television was just another dream whose specifics were written on a cloud.

Philo boarded the train in downtown San Francisco, escorted there by

two lieutenants from the Presidio, and a slouch-hatted man who didn’t speak, but whose general demeanor Philo had seen a lot of recently—he was there to make sure Philo didn’t get any cockamamie ideas.

The man needn’t have worried. When the train pulled away, Philo sat absolutely still, alone in his compartment, focusing on the boater that he kept perfectly level in his lap. He watched the straw for its interlocked patterns: zigzags, or, if he looked at them differently, arrows pointing left and right, or herringbones. When he looked up at the windows, he saw grime and soot, so he looked back down again.

When the train stopped in Sacramento, he was joined in his compartment by the most nondescript man he’d ever seen. The man dressed and behaved as if he were trying with his boater and his sunglasses to blend in seamlessly, but as there were only two of them in the compartment, Philo gave a deadly laugh.

“Yes?”

“You don’t have to worry,” Philo said. His throat was dry from having not talked in hours. “I’m going home.” The man didn’t reply, so Philo said, “I know you’re one of them, checking up on me.” Briefly, he fumbled, as it was possible he wasn’t one of them at all, and now Philo had embarrassed himself in front of a total stranger, yet another indignity.

But then the man said, “I hope you don’t mind me checking up on you.”

“Well, frankly, sir, I

do

mind.” He could be sure of himself now, and with that came indignity.

“I see. Let’s talk until the Auburn stop. That’s less than an hour. Perhaps by then we’ll have an understanding.”

“Oh, I understand already. I’m not going to tinker with television anymore. It’s done with. For the last two weeks . . .” his lower lip shook, and he looked down. “For the last two weeks, I have been in agony. I have been in agony. You don’t know what I mean.”

“Maybe I do.”

“You can’t.” He leaned forward, and with the same articulate intensity he had once found in front of a chalkboard, he declared, “I’m giving it up. Hang the idea. Kill it. My vocation, my passion, what was going to be my career almost killed my wife. No one can know what that’s like.”

At this the man pursed his lips. “I think I can.” He removed his boater and put it on the seat beside him. He took off his sunglasses, revealing bright blue eyes. He extended his hand for Philo to shake. And he said, “My name is Charles Carter. I very much admire your television idea. And I think I do know what you’ve been through.”

C

ARTER

B

EATS THE

D

EVIL

NOVEMBER 4, 1923

Yes, magic is on the decline. People have lost interest in the black art. Theatrical managers throw up their hands when asked to bill it. All the greatest magicians are dead or retired. I do not know what we shall do.

—MARTINKA, the great magic dealer (1913)

Never in any fear and never in any danger. It is a wonderful thing.

—HOUDINI, after flying solo in Australia (1910)

In San Francisco, where misdemeanors were mostly forgiven, if not welcomed, the penalty for posting bills on the sides of buildings was a startling thirty dollars. A boy paperhanger could never pay this; nor would his employers. With eight large theatres and dozens of smaller venues all booking acts and motion pictures and exhibitions, however, the paper, legal or not, had to be hung. From midnight until dawn, Tally’s Gulch and Market Street and the Tenderloin and North Beach were overrun with boys whose best qualifications were quick wits and stealth. Working in trios, one holding the heavy paste pot, another the sheet rolls, and a third working the brushes and hangers, they could cover a block in a few short minutes.

However: a poster put to the glue at midnight would undoubtedly be covered by another put up at 3

A

.

M

., so the game was to wait as long as possible—but not long enough to be caught by the sun or the occasional predawn raid of the paddy wagon.