Celandine (31 page)

Authors: Steve Augarde

I’ll put it in my . . . pocket

. Those were the words she had heard, as she had knelt beneath the wagon. Pocket. Did he mean pouchen – one of the pouches that the Gorji sewed into their clothing?

There was a flap on the piece of hanging material. Una lifted it, and found that she could put her hand inside the cloth. Again the faint jingle of sound. The tips of her fingers touched . . . metal? Bits of metal – loose, and separate. She drew a piece from its hiding place and studied it in the moonlight. A small metal disc, smooth-edged, faintly patterned – and of no interest to her. She threw it lightly onto the grass.

How many pouchen would two giants have between them? She might still be searching at

sun-wax,

and it was too cold to hope that they would sleep for so long.

I’ll put it in my . . . pocket

. It had been the deeper of the two voices – that much she remembered – but which giant did that voice belong to? She must find it . . . must find it . . .

A thought came to her. Perhaps if she could not find the Touchstone, the Touchstone might find her? Aye. Perhaps. She would try.

Una placed her hands as near as she dared to the body of the second giant, allowing her outstretched fingers to hover above the torso of the sleeping form. Eyes half closed, she tried to leave this strange place behind, to let her hands be drawn where they would go. Find me. Tell me where to look . . .

Her breathing fell into the deep sighing rhythm of the giant’s breathing, slowly in, slowly out . . . slowly in . . . and slowly out. Her eyes were closed now, and she drifted into the darkness. Once again she knelt beneath the Gorji wagon, breathing out . . . breathing in . . . out . . . and in, watching, listening. Frightened. And once again she heard the giant’s voice.

I’ll put it

. . . breathing out . . .

in my . . . pocket

. She heard him say it, saw him do it, felt him breathe it now. This was the one. Aye, this was the one.

She half opened her eyes again, watching her hands, floating like pale birds’ wings above dark waves . . . searching . . . circling . . . descending. And finding. Here. It was here. She could feel the pull of it, seeking for her . . .

Her fingertips touched the creases of the material, gently explored the rumpled folds, found the opening

of

the pocket. Breathe out, breathe in . . . slowly . . . slowly . . . there. Her hand closed around the Touchstone, and . . .

Clanggg!

She was no longer breathing.

The tang pealed out again and again. Ickri . . . dickri . . . dockri . . . quatern . . .

Una watched in horror, unable to move, as the last echoes of the tang faded into silence. The giant opened his eyes. He looked straight at her and smiled.

‘An angel . . .’ His voice was soft, barely a murmur. ‘Angels to watch over me . . .’ he raised a hand towards her face, but lowered it again without touching her, ‘when I’m . . . soldiering . . .’ The eyes grew vacant, rolled upwards slightly, and then closed once more.

Una waited, motionless, feeling the silence steal about her shoulders. Then carefully, carefully, she drew the Touchstone from the depths of the giant’s garment and stepped back, watching for a little longer. He was asleep.

The Stone was safe, and she could breathe again. She backed away a few more paces, still cautious, still unwilling to believe that the Gorji could really slumber through the sound of the tang. Finally she turned away – but then very nearly let go of the Touchstone for the third time that terrible night. She was standing face to face with the thing that she had been hiding behind earlier, the stone carving that one of the giants had mistaken for her, and called . . .

angel

.

Pale and beautiful it stood, a winged figure on a

raised

platform of stone, head bowed so that it looked down upon her. In its cupped hands it held something small and round, so that Una, with her own hands cupped about the Touchstone, felt that she was staring up in wonder at an image of herself.

And yet what a poor imitation she was of such a perfect creature. The wings of this vision were the graceful wings of a powerful bird, feathered pinions that could fly across the universe – to Elysse and back again, if need be. Her own wings could scarcely lift her over a hedge. And the descending folds of that glistening gown mocked the earth-stained shift that hung about her scratched and bruised body. She looked closer. The object that was born so lovingly in those cupped hands was a heart.

Had the Gorji made this? Were the foolish ogres, the destroyers, the wreckers of all that existed, truly able to fashion such things? This was some creature of a higher tribe – more akin to the Ickri than the Gorji – and yet she had never heard tell of them.

Angels

.

Una knelt and touched one of the delicate bare feet, letting her palm rest on the smooth white stone, half surprised not to find it warm and alive. The figure was raised upon a block of darker stone into which strange markings had been carved, small groups of shapes divided into rows. Some of the shapes were repeated. Here was one like another, and there it appeared again. Una let her finger trace the shapes, following them along the lines, feeling the clean precise edges of the cut stone. She was reminded of the faded blue markings on the parchments that had

been

her guide at the beginning of this journey. Some of those markings had been similar to these. Did they have some meaning that the Ickri had once understood, but had now forgotten?

The wind had changed. Una was aware of it as she stood up and backed away, still puzzling over the lines of markings. The air was warmer. A small sound made her glance over her shoulder at the giants. One of them had moved a little, but still they slept.

The Ickri tribe’s journey was nearly over, Una realized. Something in the urgent beating heart of the Touchstone told her so, and she must leave this place now and carry that news to her father. The tribe would be waiting for her. She knew that they were safe. And spring was here at last, born on the changing wind, this she also knew. But the strange markings beneath the angel’s feet – these had no meaning for her. Some things she could divine, and some things she could not.

Chapter Thirteen

NOW THAT NINA

had left Mount Pleasant there was no longer any proof of what had really happened that night at the swimming pool, and so Mary Swann and Co. were in little danger of ever being found out. Celandine felt vulnerable once more, for who would be inclined to believe her side of the story – she who was supposedly half-German, and a witch to boot? Nobody.

The whispers around her grew louder and ever more persistent. She was evil, violent. She was practised in the use of vicious weapons – possibly knives, certainly boot heels. She laid curses upon her enemies, and was rumoured to dabble in black arts. Tiny Lewis’s lurid account of what she had seen in the sanatorium had been embellished many times over, so that now the entire Lower School were half-prepared to believe that the Witch had raised Jessop from the dead and caused her to float about the room like a hovering Lazarus. Such a person was too dangerous to be tolerated, would have to be dealt with, must be stopped.

And yet they were frightened of her, Celandine knew that. If ever she chanced to find herself alone with one of her enemies – walking towards her in a corridor, coming out of one of the washroom cubicles, picking up a book from the library – then that person would sidle past her nervously, eyes half averted but still watchful. None would dare confront her, yet the very thing that protected her, her reputation, was also the thing that set her apart. They were frightened of her, and so they hated her. She had seen things that they would never see, knew things that they would never know – but she also knew that eventually they would destroy her for being different. She must escape.

Escape! The thought of it was like a window opening on to the day. Why had it not occurred to her before? This was a school, not a prison. She would write to her mother and beg that she might be taken away, just as Nina had been taken away.

No. That would take too long – and her mother might refuse. She would simply leave. Straight after supper would be the best time. If she were missed at prep, it would probably be assumed that she was seeing Matron or something. She would walk down to Town station, catch a train, and go home to Mill Farm . . .

It hadn’t worked. How stupid to have tried to run away whilst still in her school uniform. Once again Celandine found herself in Miss Craven’s office, staring at the strange collection of stuffed animals

behind

the glass door of their display case, wondering about the otter and why it had a mackerel in its jaws. A mackerel was definitely a sea fish. Perhaps the animal was a sea otter? But in that case it was surely the wrong sort of otter to be in the company of a stoat, a weasel, and a pine-marten . . .

‘I have written to your father, naturally, and I imagine that I will hear from him in due course.’ Miss Craven was still droning on. ‘I have given him my assurance that this will

not

occur again. From now on you are gated – by which I mean strictly confined to school premises. You are barred from going into town, and from all excursions, including those that might take place during nature lessons. Under those circumstances you will remain in school and do extra classwork. I shall consider further action, once I have received a reply from your father. In the meantime you will take five hundred lines, to be handed in to me on Monday morning – ‘

I must learn that the only remedy for self-pity is self-discipline

.’ Yes, Howard, you have displayed nothing but self-pity and cowardice in running away. Where would this country be if our soldiers at the Front all decided to simply run away, as you have done? What would happen to

them

, do you suppose? Would

they

simply be given five hundred lines and sent to bed without any supper? No, I think not. Go away, then, and consider just how fortunate you are. Dismissed.’

The following week Celandine received two letters – one from her father, and one from Freddie. She very much wanted to open Freddie’s letter first, but she made herself put it to one side. It would be better to

get

the one from her father out of the way. There was just a little time before first bell, and so she took the letters back up to the dormitory and sat on the end of her bed. The thought of reading her father’s letter made her feel quite ill – a feeling that was made worse by the strong smell of paint that filled the upper floors. The corridors were being decorated and the distemper fumes made her head ache.

Her father was angry, of course. Celandine skimmed through the pages, wincing as the criticisms jumped out at her – throwing away her opportunities . . . great personal expense . . . enough worries already . . . your mother has become quite ill with strain . . .

It was unbearable. She read through to the end as quickly as she could and stuffed the folded pages back into their envelope. Later, perhaps, she would try again, but for now she was desperate to hear what Freddie had to say.

Dearest Dinah

,

At last I have a little time to scribble some letters, and have already written home as I promised I would. I have given Mama and Father all

details

so you don’t have to keep it a secret any more. We are in France, but I’m not sure where, quite. My geography was never very good, and I don’t suppose I’d be allowed to say in any case. I can at least say that I am safe and well, and some way back from the front line. Most of our regiment has been sent to ———, and just a few of us have been brought over here to help with the horses. There was a shortage of men who had experience with

horses,

and so I was picked to go. I wish I had kept quiet, because this isn’t much different to being back at Mill Farm, apart from the noise, which is terrible and goes on day and night. I spend most of my time mucking out, and holding the horses while Corporal Blake tries to shoe them, and when I’m not doing that I’m loading up the wagons with crates of munitions. I have only held a rifle once since we arrived here

.

The worst of it is the rain and the mud, although I am not so badly off as those poor blighters in the forward trenches. At least I have somewhere dry to sleep. Last week a man was ——— for ———

. . .

Most of the last couple of paragraphs had been obliterated, inked out with a heavy black pen. The letter had been censored. Celandine held the page up to the light, trying to work out what Freddie had been trying to tell her.

Last week a man was

. . . what? Shot for desertion? For cowardice? This was her guess, because of the conversation they had had at Christmas. She imagined the picture that Freddie had perhaps tried to paint, of a poor frightened soldier sitting upon a chair, blindfolded and shaking in the early morning drizzle. Unable to take it any more . . . an attack of the jim-jams . . . a deserter. A coward.

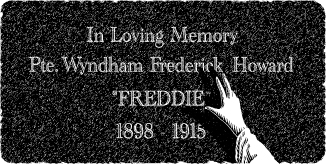

Was she a deserter and a coward too? Perhaps she was. Perhaps her father was right, and she should simply try harder. Perhaps Miss Craven was right, and she should count herself lucky.