Celandine (34 page)

Authors: Steve Augarde

Celandine shook her head.

‘I don’t really like tunnels,’ she said. ‘And I just feel like being quiet. I’m just happy to be quiet. And to sleep.’

‘Ah. ’Tis the same wi’ us all,’ said Elina. ‘We’m

none

of us so lively. Once the season do turn, then we med turn wi’ it.’ She paused at the chamber entrance. ‘Little Loren have been asking after ’ee,’ she said. ‘Most taken wi’ his letters, he be, and wanting to show ’ee.’

Celandine laughed. ‘Is he? Then I’ll get up, soon,’ she said. ‘It’s time I did.’

Her legs felt weak and achy as she stood barefoot at the cave entrance, her navy mackintosh slung around her like a cloak. She looked out upon the dripping woodland and shivered. She had not arrived at a good time. Winter had yet to loosen its grip, and the endless wind and rain made venturing from the cave almost impossible.

Loren, standing beside her, gave a little cough, and Celandine saw the tiny cloud of his breath on the cold morning air. ‘Come on,’ she said. ‘I’ll go and put some warmer clothes on and then we can read a story. Would you like that?’

He looked up at her and nodded. His nose looked sore and runny, and the red rims around his eyes made his taut skin seem whiter than ever.

‘Aye,’ he whispered. ‘I would.’

He was half-starved, Celandine realized, and immediately felt shocked and guilty. The blue veins were visible at his temples, and the skin so stretched about his cheekbones and jaw that his teeth protruded slightly. He had not been as thin as this the previous summer.

And, now that she looked about her, Celandine saw that they were all of the same appearance, the

cave-dwellers,

gaunt and frail and pale as milk-water, their wide eyes staring from the lamp-lit shadows. They were at the mercy of the seasons, even more so than the farming community that she knew. An overlong winter, a miserable summer, and they might actually die. It was horrible to imagine. What could she do to help them? She could stop eating so much of their food, she decided.

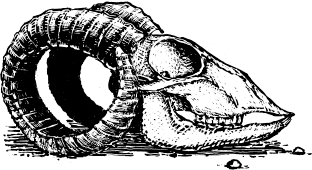

Later, with her mackintosh still draped about her shoulders, Celandine knelt among the cave-children to watch them play. She wrinkled up her nose at the gruesome focus of their game – a battered and ancient ram’s skull with great curving horns and long yellow-stained teeth. A ghoulish sight it made as it lay in the middle of the cave floor, grinning horribly at all around, as though it had just risen from the underworld.

The ram’s head was positioned between two chalked lines near the cave entrance. Behind these lines the children crouched, one group to either side of the skull, so that an empty eye-socket faced each team. With their pinched little faces frowning in concentration, the cave-children pushed up their ravelled sleeves and took turns to flick tiny coloured pebbles at the skull – the aim being to try and land the pebbles into the gaping hollows where the eyes had once been.

‘Blinder!’ This was the name of their game, and it was the quiet exclamation that went up whenever a score was made. Even in the excitement of the moment the players’ voices were seldom raised.

When each child had taken a turn, any pebbles that had lodged in the eye-sockets were fished out again, to be counted up. ‘Ickren, dickren, dockren, quatern, quin . . .’ So strange, the murmured words that kept the tally. The side that had scored the most took a corresponding number of pebbles from their opponents. It was a cross between marbles and tiddleywinks, thought Celandine, if a rather sinister one.

Loren leaned towards Celandine and placed a bright red pebble in her palm. She looked at the little stone. It was beautifully polished – as shiny as a blob of sealing wax, or a jumping bean.

‘Goo on,’ said Loren. ‘Gi’ us a blinder.’

‘Ay, Celandine. Try thee hand.’ Goppo, the champion player, grinned up at her. He spat into his grubby palms and vigorously rolled his own pebble between them – an encouragement for her to do the same.

‘Shall I?’ Celandine could not quite bring herself to spit on the pretty stone that Loren had given her, but she blew upon it instead, just for luck, and then balanced it between finger and thumbnail as she had seen the others do. She looked across at the skull, ignored the mocking challenge of that deathly grin, and tried to concentrate upon judging the distance.

In the very wishing-moment that she flicked up her thumb, Celandine somehow knew that she would succeed. The stone flew from her hand, rose and fell in a graceful arc and dropped straight into the hollow of the eye-socket, like a bird into a nesting box. A tiny rattle of sound and that was it. Perfect.

‘Blinder! Blinder!’

‘Oo! Did ’ee see ’un goo?’

Some of the cave-children jumped to their feet, their faces lit up with excitement, but Celandine remained kneeling, staring at the ram’s skull, amazed at what she had managed to do. She could see the little red stone, a demon’s eye that winked at her from its black socket so that the skull seemed eerily alive again in the dim light of the cave.

‘Oo! She’m

witchi

, that she be.’

Witchy? A witch? Others had said the same, and now Celandine was starting to wonder. Perhaps she really did have magic powers . . . perhaps she really could perform miracles . . .

But it was nothing more than beginner’s luck, of course. Celandine played the ram’s-head game many more times after that, taking it in turns to join with

one

team or the other. Nevertheless her first miracle turned out to be her last, and although she huffed upon her stone and rolled it between her palms, and cast a hundred magic spells upon it, she never managed to score another Blinder.

There were other side chambers leading off the main cavern, Celandine discovered, rooms that were used for work or for storage. Micas and Elina showed her what little they had to show; the collection of earthenware pots, mostly empty, wherein they stored dried food against the winter months – rose-hips, crab apples, nuts and wild grain. They showed her the weaving chamber, and how they divided the precious scraps of wool and fur and horsehair that they found into separate baskets, to be eventually woven into something like cloth upon a rough wooden frame. They showed her the wash-place – an eerie echoing chamber where icy water trickled among the black rocks, to disappear through cracks and crevices far below.

They would have shown her, too, what lay further beyond, through the honeycomb of low tunnels that led away from the main chambers, but here Celandine would not venture. Where the cave-dwellers could just about stand upright to enter these places, she would have to crawl, and she was nervous of doing so. From time to time she heard metallic tapping sounds echoing along the passageways,

tink-tink-tink

, and when she asked Micas what they did back there, he simply said, ‘We worken the tinsy.’

Later he emerged from one of the tunnels with a sack over his shoulder. Celandine almost laughed when he opened the sack, because it contained metal-ware – plates and bowls, and bits of jewellery – and she thought he looked like a burglar who had lately robbed a mansion. The objects were dull and tarnished, but when she looked closer she saw that they were finely engraved. Tiny figures she could see in the flickering lamplight, beautifully drawn, amid many scenes. She looked closer still, beginning to take an interest. So exquisite, these things were, in such primitive surroundings. What were the figures doing, and what did it all mean?

‘’Tis we,’ said Micas. ‘And all our story. We maken our tales so, as the Gorji do maken theirs i’ a book, as ’twould seem. See – here be old Emra, that was slain b’ the Ickren, and here be a Gorji dwelling, a-standing on wooden legs long afore the waters dried. We were but tribe and tribe, then, and lived upon the waters, the Naiad, and the Ickren alike.’

The words made little sense at first, but as the rainy days passed Celandine came to understand more, learning to unravel the pictorial account of the woodlanders’ history. She was drawn in by the story of the Touchstone, the magical object that had been stolen by the wicked tribe that Micas called Ickren, although she didn’t really believe that it could be entirely true. There may have once been such a stone, she thought, but never a one that could lead its followers up to the very heavens. And these Ickren, if they had ever actually existed, had also been

exaggerated.

She could accept the bows and arrows, but the wings were surely an added fancy. She became fascinated, though, and she continued to work her way through the picture fables, as the cave-dwellers themselves worked their way through the Gorji fables that were hidden within a different kind of code – letters.

They had made progress in her long absence, and now when they gathered in the draughty cave entrance to look at the chalk marks upon the wall, their cleverness astounded her.

MICAS

Celandine wrote the word upon the wall and said, ‘What do these letters spell?’

‘Micas! ’Tis Micas!’ She had hardly got the question out before Loren had got the answer.

‘Yes! That’s

very

good. All right, then. Let’s see if somebody else can answer the next.’

One by one she wrote out their names, and with very little prompting each could recognize their own – Tammas, Garlan, Esma, Poll. Whatever she wrote on the wall, they could eventually decipher. They learned faster than she could teach them, and the dreary days of confinement were illuminated by simple chalk marks upon stone.

Still the wind and rain continued, and spring seemed as far away as ever. Celandine struggled to work out exactly how long it had been since she had run away. Eight days? Ten? And what was happening now, in that other world beyond the briars? She thought of the note that she had left on the paddock

corner

post and, not for the first time, she felt a stab of guilt.

‘

Dear Mama, I shall be staying with some friends and neighbours for a while, near Taunton. I am perfectly safe and well. Please don’t worry about me. Love, Celandine

.’

How inadequate those few words had been, and how misleading. But if she had written more, and been more truthful, would that have caused less worry? Probably not. She pushed the thought away from her.

Celandine grew tired of reading from

Aesop’s Fables

and fairytales, and wished that she had more books. If only she had thought to bring some with her. It occurred to her that she might write stories upon the wall, but this seemed too laborious. A song. She could write the words of a song.

The cave entrance looked as though it had been smeared with whitewash, so many times had it been written upon, and then wiped down with a wet scrap of cloth, but the fresh words were readable, and she could hear the ragged little group whispering behind her – already attempting to translate as the chalk marks appeared. ‘E-arly on . . . one . . . mo . . . morn . . .’

‘This isn’t a story,’ she said. ‘It’s a song that I learned when I was little. If I sing it, then . . . well, you can look at the words, and see if you can read them. Then we could all sing it together.’

The pale faces looked up at her, puzzled but attentive. She was hungry, she realized. Her tummy was making funny noises. Outside the entrance the

wind

had dropped, and she was aware of the silence.

‘

Early one morning, just as the sun was rising

,

I heard a maiden sing in the valley below

. . .’

Celandine faltered, and nearly stopped singing altogether – so shocked were the expressions that greeted her efforts.

‘

Oh never leave me, Oh don’t deceive me

. . .’

What on earth could be the matter with them?

‘

How could you use a poor maiden so?

’

They were regarding her as though she had just thrown a fit – shrinking against one another as if for support. Was her voice so very terrible?

‘What is it?’ she said.

A slanting sunbeam stole into the entrance of the cave, fiery bright, so that the dusty little gathering was bathed in its glow. The huddled cave-dwellers shielded their faces from the unaccustomed glare, but still their eyes were fixed upon Celandine, in awe and wonder . . .

‘Again,’ they whispered. ‘Show us how ’twere done . . .’

It took Celandine a while to understand what they meant.

‘Don’t you know how to sing?’ she said. ‘Has nobody ever taught you?’

Spring had finally arrived then, with that first shy beam of light, and every creature, every twig and leaf, seemed in a hurry to make up for lost time. The sun shone warm upon the damp forest, so that it steamed like a tropical garden and hummed with the activities of

its

inhabitants. Everything was alive, and awake and busy.

Celandine viewed it all from the mouth of the cave, and felt oddly reluctant to venture out. She had been content to hide away in the darkness, neither happy nor unhappy, floating in a mist of pictures and stories. But here was bright daylight to be faced once more, sharp and clear, and beyond the bounds of the forest lay the world that was the cause of all her pain. If she once stepped forth into the brilliant sunshine, she would be that much closer to everything she had run away from – and that much closer to being hauled back. She didn’t want to be awoken from the comfort of the darkness.