CELL 8 (12 page)

He drank a lot of water. It was ten in the morning and he was already on his third bottle of expensive mineral water from the shop on the corner by the garage. He had put on weight with all this damn sitting, and water instead of morning coffee meant a lot of running to the toilet, but it worked.

He had just poured a glass when the call came from the head office in Washington.

They didn’t say much. But he realized that he should put the water to one side, that today had just taken on another dimension.

He was given a phone number, a Marc Brock at Interpol, he was to call him, he had all the information there was.

Having searched through all the accessible databases, a procedure he repeated three times, Marc Brock had gradually come to understand over the past hour that whatever it was that wasn’t right, was in fact right.

The man in the photo, the man who was wanted, was a dead man. Every single time. And yet, it couldn’t be right. Not if you took into consideration

where

he died.

Brock had phoned the person who had sent the information, the officer who had requested help: someone called Klövje in Sweden. He had had time to reminisce about Stockholm again, the woman whose name he still remembered, and he had envisaged the beautiful city built on islands with water everywhere while he waited for an answer—they had walked around hand in hand for several days—with the receiver to his ear, and he had wondered who he would have been now, if it had worked out, if he had stayed with her.

The Swedish voice had been formal and spoken correct English with a Swedish accent. Brock had apologized, realized that he had no idea what time it was—the afternoon, he had suddenly remembered when Klövje answered the phone, six hours’ difference, that was it.

The stiff smile, the uneasy eyes.

Brock had insisted. He wanted to check the photo he had of a man who called himself John Schwarz. He wanted to compare, not with the photo stuck in a Canadian passport, but with the real thing.

Klövje had confirmed the picture’s veracity twenty minutes later. He had been to the jail, the cell where the suspect was being held, and he had with his own eyes seen that both faces, the one in the passport and the real one, were one and the same.

Marc Brock had thanked him, asked if he could get back to him, and lifted the receiver again as soon as he had put it down, convinced that his colleagues over at the FBI head office would think he was completely crazy.

Kevin Hutton had been ordered to call Interpol, someone called Brock.

He would do it in a moment.

He swung around in his chair and looked out over Cincinnati, where he’d lived since he applied for and got the job in the local Ohio office. The tall buildings, the busy main roads.

A few more deep breaths—he was still shaking.

Because if the first summarized details from the FBI head office were correct, he should open the window and scream out across the noisy city.

Because it just wasn’t possible.

And he, if anyone, should know.

Marc Brock confirmed everything.

Hutton heard the anxiety in his voice and he realized that Brock also found it hard to believe, that he would happily forward what he had because then he wouldn’t need to deal with this shit anymore.

You’re dead, for fuck’s sake

.

Kevin Hutton had immediately recognized the man in the picture.

His face was twenty years older. His hair shorter, skin paler.

But it was him. He was sure of it.

He opened the window, leaned out into the cold January air, closed his eyes, and shivered. He closed his eyes in the way you do when you just don’t want to understand.

SHE HAD MOVED HER HAND.

He should sing, laugh, maybe even cry.

Ewert Grens couldn’t face it.

All these years, he had somehow given up hope. And now, he didn’t know, it was sorrow, guilt, loss. Like a curse. The more she waved, the clearer everything else became. What she wasn’t doing. The damn guilt that he’d learned to suppress, it was hounding him again, he couldn’t escape it, it knew where he was and smeared him with its terrible fucking blackness.

They had had each other. And he had driven over her head. A split second, then they had ceased to be, midstep.

He loved her.

He had no one else.

He wasn’t going to go home this evening. He would sit here with the Schwarz investigation in front of him until his eyes couldn’t see any longer, then he would lie down on the sofa, sleep, get up again when it was still dark; he needed the dawn.

Grens ate a sandwich with some cheese from the vending machine out in the corridor by the coffee machine, the plastic packaging was greasy, butter or something else.

She had done a good interview, Hermansson. Schwarz would trust her, it wouldn’t be long now. Strange guy. As if he was trying to hide from them, despite the fact that they were sitting on the chairs directly opposite him, looking at him.

There was silence in the room. He looked at the shelf on the wall and the cassettes and the photograph of Siw, but it didn’t work. Anni had waved and there was no room for music in the room. Just wasn’t. Just fucking wasn’t.

He had never felt like this before.

It was her voice that comforted him, that filled the room with what had once been.

Not today. Not now.

Jens Klövje knocked and pushed open the door that was standing ajar. He was red in the face, having just walked fast along the corridor and down the steps from C Block. He was carrying a bundle of papers in his hand, still warm from the fax machine, and explained that Ewert might want to see what was written there, that he was leaving it with Grens and was going back to his desk to wait and see if any more had come.

Grens finished his cheese sandwich, brushed some crumbs from his desk into the greasy wrapper in the bin.

He looked at the thin pile of documents, counted five pages and picked them up.

He had read several thousand reports written by overzealous policemen before. This one was obviously American and had different names and different addresses, but was just as detailed, just as fearful of making formal errors as all the others.

Grens stood up. He was restless. There were other thoughts inside him, far more interesting than Schwarz and his past. A couple of times around the room, he could feel the silence now, he wasn’t used to it and it was louder than either Siw or chatty investigators.

She had done something the bastards had claimed was impossible.

It had taken twenty-five years, but she had done it, and he had seen it.

He knew that he was pushing it, but he couldn’t help it. He sat down again and dialed the number of the nursing home.

“It’s Grens. I know it’s late to be calling.”

A brief hesitation.

“I’m sorry, but you really can’t talk to her at this hour.”

He recognized the voice that had answered and that continued, “You know she needs her sleep. And that she’s in bed by now.”

Susann, the young woman who wanted to be a doctor, who was going to accompany them out onto the water. He tried to be friendly.

“It was you that I wanted to speak to. About our little trip later on in the week. I just wanted to make sure that you’d been informed.”

It was hard to make out whether she sighed or not.

“I’ve been told. And I’ll be coming with you.”

He apologized again, then hung up, maybe she sighed again, he didn’t know, quite simply chose not to listen.

He picked up the American fax again. More focused now—he’d rung and checked, and she was asleep, she was comfortable. He might as well work, continue searching for the man who had once been John Schwarz.

Grens leaned forward.

That feeling. When it’s the start of something.

He read on and it slowly dawned on him what Klövje had meant, why he had been so out of breath, why his swollen face that had popped around the door a while ago had been so red.

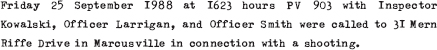

A person had died. She had been lying on the floor in a house in some goddamn hole called Marcusville and she had gradually ceased to be.

Jens Klövje had said that there was more to come. Other documents from an investigation carried out eighteen years ago in connection with the man who now called himself John Schwarz and who was sitting in a locked cell in the detention center a few hundred yards away.