Cell Phone Nation: How Mobile Phones Have Revolutionized Business, Politics and Ordinary Life in India (26 page)

Authors: Robin Jeffrey

Attempts to use mobile phones and digital technology to benefit rural people produced sometimes unexpected results which in turn pointed in directions where society may take technology. IKSL (IFFCO Kisan Sanchar Ltd), for example, was set up in 2007 as a collaboration between one of India’s largest fertiliser producers, the cooperative IFFCO, Bharti Airtel, the telecom giant, and Star Global Resources Ltd, a finance company. By the end of 2011, more than a million agriculturalists had bought into the system by buying an IKSL SIM card for their mobile phone. The card—a Bharti Airtel card of course—allowed them to do everything a mobile does, but it also sent them five voice messages a day about agricultural conditions and opportunities and a helpline for specific advice. IFFCO brought 40,000 agricultural cooperatives around India into the program.

68

By the end of 2011, IKSL claimed more than a million active users (and 8 million subscribers) in eighteen of India’s twenty-eight states.

69

Though these numbers meant that fewer than two per cent of India’s 90 million ‘farmer households’ used the service regularly,

70

the service was capable of growing—’to scale up … so that the large rural base is not left [out]’, as the IKSL website stated. But it warned: ‘Many initiatives fall short in replicability on a large scale’.

71

The evolution of IKSL showed how mobile phones might be adapted to fulfil people’s needs in rural India. For Bharti Airtel, it was worth being involved in enterprises that promised to increase mobile phone use in the countryside. Part of the justification that the founders of IKSL put forward for the project was that in 2006 rural mobile-phone penetration was low: less than two per cent of the population. Within five years, the promoters claimed this had risen to 20 per cent, partly as a result of IKSL.

72

For the fertiliser cooperative, the phone project provided a chance to improve the services to its members; the finance company saw possibilities of finding new ways to mobilise deposits. And the program seemed to make money.

73

As with EKO, education and promotion were essential. ‘We bought and distributed mobile handsets to village leaders’, Ranjan Sharma, one of its founders, told a journalist about the early

days of the program in 2005. The respected recipients received voice messages about agricultural conditions that they passed on to the farmers.

74

The program began with an old premise—the ‘two-step flow’—that messages were influential when they were communicated first to respected local figures who passed them on to their neighbours and associates.

75

The program also underlined the strengths of the mobile phone: it was based on the

voice

—you did not need to be able to read or write—and it was cheap and easy to use. Though the pilot program found it necessary to give phones free to local leaders, by 2007 the take-up of mobiles, even in the countryside, was so strong that the service claimed 800,000 subscribers.

76

Empowering, ensnaring or just chatting …?

Experiments with mobile phones ranged from the modest ones of boatmen on the ghats in Banaras to the grand designs of EKO to bring banking to the masses and of IKSL to improve the productivity of Indian agriculture. The magic lay in simplicity and economy. A mobile phone, unlike so much technology of the past two hundred years, was able to be owned and used by the vast majority of Indians. By 2010 the cost of handset fell to around a week’s wages for an agricultural labourer, and one rupee (about two cents US) could buy four minutes of talk time. To use a phone required familiarization with a dozen keys on a keypad and memorization of the sequence required for particular purposes. People who could not read and write often had excellent memories. As the boatmen at Banaras showed, a little literacy was enough to make a mobile phone hum with activity. Moreover, the phone prompted improvements in literacy because better literacy brought more ways to exploit the phone.

77

Being able to bypass reading, writing and print was an immense virtue for a tool for mass use and recalled the enthusiasms of Marshall McLuhan for a ‘global village’ in which people were liberated from the bondage of print. But the mobile phone did not lead there. Rather, it lured users down a path that made literacy desirable, useful and attainable and initiated them into a world of record-keeping, data-bases and regular exchange with the apparatus of government. A mobile phone user could not avoid the state, but users could now engage with it on

more systematic, predictable and equal terms. At the same time, the mobile phone was the most effective device India ever had for locking its people into connections with the state in ways that could be verified and monitored. The state could find and track its citizens as never before.

The examples of cell phones in daily commerce focused on people doing relatively small things. As they went about their mobilephone-related business, they were also enriching the great capitalist families and corporations that ‘owned’ slabs of Radio Frequency, built the transmission towers, sold the phones and installed the technology. And government, or terrorists, could shut it all down by threatening the operators, turning off the electricity or blowing up the towers (

Chapter 8

). Mass mobiles were scarcely a cure-all for poverty or oppression, though

in some circumstances, the ability to communicate freely and cheaply tilted balances and changed equations, as the consideration of political organisation, which we explore in the next chapter, suggests.

Illus. 1: Multi-tasking. A boatman ferries passengers and checks his phone. Banaras ghats in the background. July 2012. (Photo: Sachidanand Dixit with thanks).

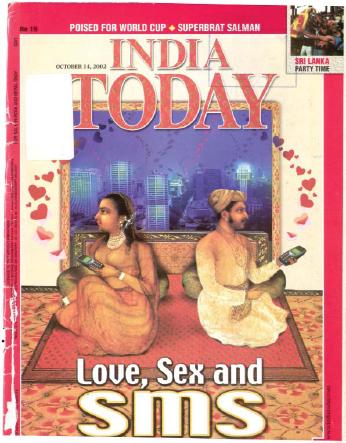

Illus. 2: Love in a time of SMS.

India Today

’s cover art gives 17th-century lovers 21st-century devices. (

India Today

, 14 October 2002, with permission).

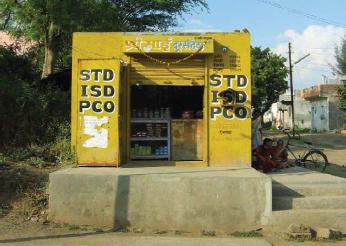

Illus. 3: Vanishing species. Yellow-painted Public Call Offices (PCOs) were everywhere but are fast disappearing. (Photo: Wikipedia, downloaded July 2012).

Illus. 4:

Swamy’s Treatise on Telephone Rules

. The 850-page guide to the mysteries of the government telephone monopoly was a profit-maker until as late as 1993. (Photo: Robin Jeffrey).

Illus. 5: Duelling telcos. Vodafone and the government service provider BSNL fight for attention in Banaras. October 2009. (Photo: Assa Doron).

Illus. 6: Cheeka to the rescue. The mobile phone dog started her advertising career with Hutch and helped move the brand to Vodafone. Cheeka, like the cell phone service she represents, is always there when you need her or so the ad would like us to believe. (Ogilvy & Mather and Vodafone, with permission and thanks).

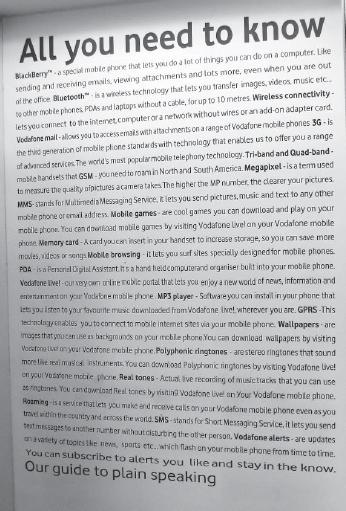

Illus. 7: Educating consumers. In one of the many Vodaphone outlets in Banaras, a placard explains to English speakers the wonders of mobile communication—from ‘SMS’ to ‘3G’ and ‘Wifi’. October 2009. (Photo: Assa Doron).