Cell Phone Nation: How Mobile Phones Have Revolutionized Business, Politics and Ordinary Life in India (29 page)

Authors: Robin Jeffrey

Illus. 32: For some, a phone in a woman’s hand was a disturbing accessory.

Mobile Wali: Woman with a Mobile Phone

. Singers: Manoj Tiwari, ‘Mridul’ and Trishna. Publisher: WAVE VCD. (YouTube, 23 July 2012. Screen dump by Paul Brugman, Australian National University).

Illus. 33: ‘The Washerwoman with the Mobile Phone’. Cover of DVD entitled

Mobile Wali Dhobiniya

. Singers: Dinesh Lal Gaundh and Noorjehan. Publisher: GANGA VCD. (Photo: Paul Brugman, Australian National University).

Illus. 34: Youth market. ‘Adult film star’ Sunny Leone became brand ambassador for Chaze mobiles. Chaze chased younger buyers with the offer of cheap multimedia phones. (

My Mobile

, 12 July 2012, with permission and thanks).

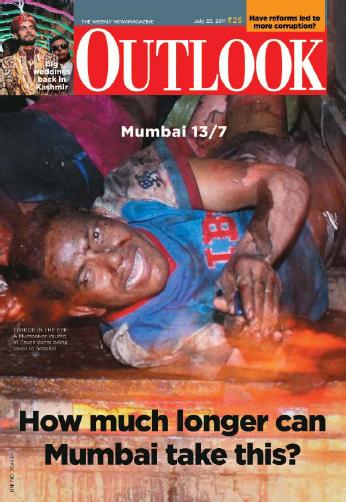

Illus. 35: Terror and an amulet. A burned victim of the Mumbai bombings of 13 July 2011 clutches a connection to aid and succour—his cell phone. (

Outlook

, 25 July 2011, with permission and thanks).

Illus. 36: Brain tumours, heart attacks, cancer and impotence are some of the things mobile phone radiation can do to you, according to this advertisement on a men’s toilet in New Delhi in July 2012. Prabhatam, the advertiser, offered ‘radiation-safe mobile solutions’. (Photo: Assa Doron).

Illus. 37: SIM card throwaways. Discarded telecom goods pose growing challenges. The tiny SIM-circuit portion of these cards has been popped out and inserted in a phone. (Photo: Toxic Link, with permission and thanks).

Illus. 38: This adult-sized mound of waste was being picked over by cottage-industry waste-recyclers. Outskirts of New Delhi, 2012. (Photo: Toxic Link, with permission and thanks).

If a Sudra … listens in on a Vedic recitation, his ears shall be filled with molten tin …

Dharmasutra. The Law Codes of Ancient India

, Patrick Olivelle ed.

In an old India, caste and class determined how much freedom a person had to travel and communicate. Material conditions also imposed restrictions: roads were poor; conveyances were limited and costly; and letters required literacy, writing materials and messengers. More important, low-status villagers, such as agricultural labourers, were prevented from moving about without the consent of their superiors, and religious texts decreed that low-caste people should be punished for even hearing, much less repeating, certain religious incantations. The constitution of independent India in 1950 aimed to end such distinctions and declared all citizens equal; but the success of legislated egalitarianism was spotty, and immense class differences and prejudices remained. It was only in the first decade of the twenty-first century that cheap mobile phones began to overcome the remnants of these constraints. In the hands of committed political workers, honest officials or outraged citizens, the phone became a simple tool for organising politics, disseminating news and alerting sympathetic authorities to failures of law and government. The cell phone gave people on the margins chances to communicate that were unimaginable to their forebears.

‘Smart mobs’ in the world

Journalists

and scholars quickly recognised the ability of individualised, portable communications to gather crowds. Vicente Rafael’s article, ‘The Cell Phone and the Crowd’, made the Filipinos who streamed into the streets of Manila to demonstrate against President Joseph Estrada in January 2001 as prominent as the Kerala fishermen whom the economist Robert Jensen and others popularised (

Chapter 5

).

1

‘At its most utopian’, Rafael wrote, ‘the fetish of communication suggested the possibility of dissolving, however provisionally, existing class divisions’.

2

No such thing of course happened. The president was brought down; the crowds soon dissolved; and the class divisions of the Philippines did not disappear. Clear-headed analysts like Howard Rheingold, drawing on the writing of Rafael and the experience of the Philippines, used the term ‘smart mobs’ as the title of his remarkable book

Smart Mobs: the Next Social Revolution

, published in 2002.

3

‘Smart mobs’, Rheingold wrote, ‘consist of people who are able to act in concert even if they don’t know each other’. He saw immense potential in the independent communication that mobile phones made possible. ‘Groups of people using these tools will gain new forms of social power, new ways to organize their interactions and exchanges …’

4

Rheingold reflected on how cell phones fostered demonstrations against the World Trade Organization in Seattle in 1999 and how students, using simple digital video, recorded violence at a protest in Toronto in 2000.

5

Two other global events became part of the literature: the South Korean presidential elections of 2002 and the Spanish general elections of 2004. In Korea, the outsider for the presidency, Roh Moo-Hyun (1946–2009), won a surprising victory, even though he was disparaged in mainstream media and had his website shut down for most of the campaign. A large measure of credit for the victory appeared to lie in his ability to reach young voters, recent owners of mobile phones. In the 1997 presidential elections, only a third of young people voted; in 2002, ‘mobilized through mobile messages’, 60 per cent of young voters turned out to vote for Roh Moo-Hyun, and he prevailed.

6

In Spain, two years later, the Madrid train bombings that killed more than 190 people happened three days before national elections. The ruling party blamed Basque separatists in the expectation that its strong stand against separatism would win voter approval. The problem was that the charges were quickly revealed to be unconvincing, and connections with al-Qaeda-inspired terror groups became apparent. Though the government had a fairly tight hold over mainstream media, mobile phones bypassed them. Cell phones brought tens of thousands of people into the streets to protest against ‘government lies’ and transmitted hundreds of thousands of voice and text messages highlighting government deceit and pointing to other sources of information. The government lost the poll. ‘This experience in Spain’, declared Manuel Castells and his associates, ‘coming three years after the flash mob mobilization [in the Philippines] …, will remain a turning point in the history of political communication’.

7

Incidents

such as these made the unpredictable potential of the mobile phone obvious. It possessed the ability to let large numbers of people generate and exchange information. Such information, unlike a newspaper or a radio bulletin, had no central place of production, and enabled people to communicate rapidly and continually. It also gave them a tool with which to call meetings quickly and send the news widely. Rheingold set considerable store by the fact that individualised communication could bring many people together quickly, create a mob, smart or otherwise, and that this offered ways of challenging the powerful. But he also pointed to dangers: ‘surveillance technologies become a threat to liberty as well as dignity when they give one person or group the power to constrain the behaviour of others’.

8

Both he and Castells recognised that the latent power of the technology depended on the circumstances in which it was used. People who knew each other could form a chain of validation, each person conferring on a message her or his implicit endorsement. ‘The origin of the message’, Castells and associates suggested, was one of the ‘critical ingredients of the political power embedded in wireless technology’.

9

In certain conditions, the mobile phone made possible what once would have been inconceivable.

A lively literature has grown up around celebration and debunking of the Internet and the possibilities of digital technology to liberate or enslave. Scholars like Rheingold warned from the outset against ‘the rhetoric of the technological sublime’ and understood that the technology had ‘shadow sides’. Governments could place whole populations under surveillance, and ‘terrorists and organized criminals’ could find new ways to conquer new worlds.

10

A young Belarusian-American author wrote a book deploring ‘cyber-utopianism’—‘a naïve belief in the emancipatory nature of online communication’.

11

He quoted at length from Internet enthusiasts whose hopes were belied, and underlined the ways in which bad people and corrupt regimes used technologies to sustain and extend their activities and rule. Misguided faith in digital communications to enable meaningful change could ‘turn everyone who uses the Internet in authoritarian states into unwilling prisoners’.

12