Challenger Deep (31 page)

Authors: Neal Shusterman

“Good.”

I look at him for a moment, trying to determine whether he actually said that, or if I just heard it in my head.

“How is that good?” I ask.

“Well, it wasn’t good at the time—not at all—but it’s good now. Because now you can see the result. Cause and effect, cause and effect. Now you know.”

I want to be annoyed at him, or at least mildly irritated, but I can’t. Maybe because for once I don’t mind that he might be right. Or maybe it’s the meds.

There’s something odd about Poirot. It was on the edge of my perception, but now he moves close enough for me to realize what it is. His colorful wardrobe is gone. Instead he wears a beige

button-down shirt, with an equally uninteresting tie.

“No Hawaiian shirt?” I ask.

He sighs. “Yes, well, hospital management felt it didn’t project sufficient professionalism.”

“They’re morons,” I tell him.

That actually makes him squawk out a guffaw. “You’ll find in life, Caden, that many decisions are made by morons in high places.”

“I’ve been a moron in a high place,” I say. “I think I do better on the ground.”

He smiles at me. It’s a little different from his therapeutically fixed grin. It’s warmer. “Your parents are in the waiting area. It’s not visiting hours, but I gave them special permission to be here. That is, if you want to see them.”

I consider the prospect. “Well . . . is my father wearing a straw fedora, and is my mother walking with a broken heel?”

Poirot turns his head slightly to better regard me with his working eye. “I don’t believe so, no.”

“Okay, that means they’re real, so yes, I want to see them.”

Anyone else might look at me strangely for saying that, but not Poirot. The fact that I’m developing “reality criteria” is a good thing as far as he’s concerned. He stands up. “I’ll send them in.” Then he hesitates, regards me for a moment more, and says, “Welcome back, Caden.”

As he leaves, I resolve that, if and when I get out of here, I’m going to buy him an expensive silk tie covered with brightly colored birds.

I want to give Skye back her puzzle piece, but I can’t find it. The puzzle remains finished except for that one piece. No one is allowed to touch it, lest they face Skye’s significant wrath. Then one day she’s discharged, and the pastels take it apart, and put it back in the box for other patients. I think it’s outrageously cruel to keep a puzzle that they know is missing a single piece.

Hal never comes back, and no one ever tells me convincingly whether he lived or died. I do receive a letter, though, that is covered with lines and scribbles and symbols that I can’t read. It could have come from him, or it could be a practical joke from one of the more unpleasant patients who has since gone home, or it could be from someone who cares about me and is trying to placate me—kind of the way my parents used to write responses to the letters I sent to Santa when I was little. On this matter, I weigh all theories equally.

I never hear from Callie. It’s okay. I never expected to. I hope her life takes her far away from anything that reminds her of this place, and if that means taking her far away from me, I can accept that. She walked on water, rather than drowned. That’s enough for me.

Then one day it is finally determined that I have become one with the real world once more—or at least am within striking distance—and I’m released into the loving arms of my family.

On that final day of my “mental cast,” I wait in my room with

all my things packed in sturdy yellow plastic bags provided by the hospital. There’s nothing in there but clothes. I decided to leave my art supplies for other patients. The colored pencils were taken away by the staff when I wasn’t looking one day, leaving just plastic markers and soft pastels—things that don’t need to be sharpened.

My parents arrive at 10:03 in the morning, and even bring Mackenzie. My mom and dad sign about as much paperwork as they had to sign when I was admitted, and just like that the deed is done.

I ask for a few minutes to say good-bye, but it doesn’t take as long as I thought. The nurses and various pastels wish me well. Angry Arms of Death gives me a knuckle-tap and says “stay real,” which is ironic in ways that neither him nor his skulls can grasp. GLaDOS is having her group, and although I poke my head in to say good-bye, it’s awkward for everyone. Now I know how Callie felt the day that she left. You’re on the other side of the glass even before you step outside.

My dad gently puts his hand on my shoulder and checks in with me before we move toward the canal-lock exit doors. “You okay, Caden?” Now he reads me in ways he never did before. Like Sherlock Holmes with a magnifying glass.

“Yeah, fine,” I tell him.

He smiles. “Then let’s get the hell out of here.”

Mom tells me we’re going to Cold Stone on the way home, which she knows is my favorite. It will be good to have ice cream that you don’t eat with a wooden spoon.

“I hope you haven’t made a big deal about this at home,” I tell them, “like balloons and ‘welcome home’ banners and stuff.”

The uncomfortable silence tells me that there is, indeed, a big deal awaiting me.

“It’s just one balloon,” Mom says.

Mackenzie looks down. “I got you a balloon. So?”

Now I feel bad. “Well . . . is it big, like a refugee from the Thanksgiving Day Parade?” I ask.

“No, not really,” she says.

“Then I’m sure it’s fine.”

We stand before the exit. The inner door opens, and we step into the little security air lock. My mom puts her arm around me, and I realize she’s doing it as much for herself as for me. She needs the comfort of finally being able to comfort me; something she hasn’t been able to do for a long time.

My illness has dragged us all through the trenches, and although my trench was, well, the Marianas, I won’t discount what my family has been through. I will never forget that my parents came to the hospital every single day, even when I was clearly in other places. I will never forget that my little sister held my hand, and tried to understand what it’s like to be in those other places.

Behind us, the inner doors swing closed. I hold my breath. Then the outer doors open, and once more I am a proud member of the rational world.

An hour later, after an insanely decadent ice-cream fest, we arrive home and I see Mackenzie’s balloon right away as we pull onto the street. It’s attached to our mailbox in the front yard, bobbing lazily with the breeze. I laugh out loud when I see what it is.

“Where on earth did you find a Mylar brain?” I ask Mackenzie.

“Online,” she says with a shrug. “They’ve got livers and kidneys, too.”

I give her a hug. “Best balloon ever.”

We get out of the car, and, with Mackenzie’s permission, I untie the helium-filled brain, and release it, watching it rise up and up until it disappears.

Nine weeks. That’s how long I was hospitalized. I check the calendar hanging in the kitchen to confirm it, because it felt like so much longer.

School is already out for the summer, but even if it wasn’t, I’m not in any condition to sit in a classroom and focus. My attention span and my motivation rank up there with that of a sea cucumber. Part of it’s the illness, part of it’s the medication. I am told it will slowly get better. I reluctantly believe it. This, too, shall pass.

It’s up in the air what will happen when school starts again. I may not go back until January, and then repeat the second half of sophomore year. Or I may go to a new school for a fresh start. I may be homeschooled until I catch up. I may just go in as a junior in September, business as usual, and eventually make up what I missed in summer school next year. Advanced calculus has fewer

variables than my education.

My doctor says not to worry about it. My

new

doctor—not Poirot. Once you leave the hospital, you gotta get a new doctor. That’s the way it works. The new guy’s okay. He takes more time with me than I thought he would. He prescribes my meds. I take them. I hate them, but I take them. I’m numb, but not as numb as I was. The Jell-O seems to be of the whipped variety now.

My new doctor’s name is Dr. Fischel, which is appropriate, because he kind of does have a face like a trout. We’ll see where that goes.

I have this dream. I’m walking on a boardwalk somewhere with my family. Maybe Atlantic City, or Santa Monica. Mackenzie drags my parents onto an entertainment pier—roller coasters, bumper cars—and although I try to go with them, I lag behind and can’t catch up. Pretty soon I’ve lost them in the crowd. And then I hear this voice.

“You, there! Been waitin’ for you!”

I turn to see a yacht. Not just your run-of-the-mill yacht but one of Bond-villain proportions. Gleaming gold, with pitch-black windows. There’s a Jacuzzi, and lounge chairs, and a crew that seems to be made exclusively of beautiful girls in string bikinis. And standing at the gangway is a familiar figure. His beard is trimmed

to a goatee, and his uniform is a white double-breasted suit with gold trim. Even so, I know who he is.

“We can’t sail without a first mate. And that would be you.”

I find myself halfway down the gangway, just a few feet from the yacht. I don’t remember moving there.

“It will be my pleasure to have you aboard,” the captain says.

“What’s the mission?” I ask, much more curious than I want to be.

“Caribbean reef,” he tells me. “One that no human has yet laid eyes on. You’re certified in scuba, aren’t you?”

“No,” I tell him.

“Well, then, it’s up to me to certify you, isn’t it?”

He smiles at me. His good eye stares at me with familiar intensity that almost feels comfortable. Almost feels like home. His other eye has no eye patch, and the peach pit has been replaced by a diamond that glitters in the midday sun.

“All aboard!” he says.

I linger on the gangway.

I linger.

I linger some more.

And then I tell him, “I don’t think so.”

He doesn’t try to convince me. He just smiles and nods. Then he says in a low voice that is somehow louder than the crowd on the pier behind me, “You’ll be going back down there eventually. You know that, don’t you? The serpent and I won’t have it any other way.”

I think about that, and although the thought chills me, I can’t

deny the very real nature of that possibility.

“Maybe,” I tell the captain. “Probably,” I admit. “But not today.”

I turn and walk back up the gangway to the pier. It’s narrow and precarious, but I’ve done precarious before, so it’s nothing new. When I’m safe on the pier once more, I glance back, thinking that maybe the yacht might have vanished, as such apparitions do—but no, it’s still there, and the captain is still waiting, his eye fixed on me.

He will always be waiting, I realize. He will never go away. And in time, I may find myself his first mate whether I want to or not, journeying to points exotic so that I might make another dive, and another, and another. And maybe one day I’ll dive so deep that the Abyssal Serpent will catch me, and I’ll never find my way back. No sense in denying that such things happen.

But it’s not going to happen today—and there is a deep, abiding comfort in that. Deep enough to carry me through till tomorrow.

Challenger Deep

is by no means a work of fiction. The places that Caden goes are all too real. One in three U.S. families is affected by the specter of mental illness. I know, because our family is one of them. We faced many of the same things Caden and his family did. I watched as someone I loved journeyed to the deep, and I felt powerless to stop the descent.

With the help of my son, I’ve tried to capture what that descent was like. The impressions of the hospital, and the sense of fear, paranoia, mania, and depression are real, as well as the “Jell-O” feeling and numbness the meds can give you (something I experienced firsthand when I accidentally took two Seroquel, confusing them with Excedrin). But the healing is also real. Mental illness doesn’t go away entirely, but it can, in a sense, be sent into remission. As Dr. Poirot says, it’s not an exact science, but it’s all we have—and it gets better every day as we learn more about the brain, and the mind, and as we develop better, more targeted medication.

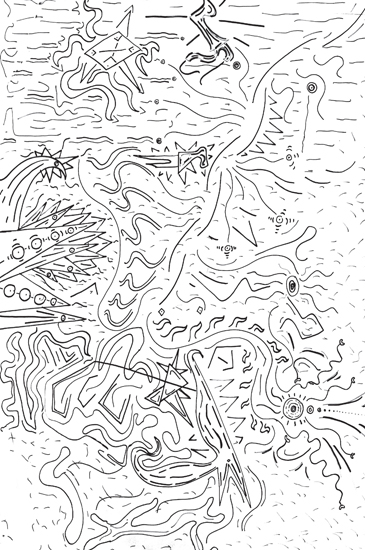

Twenty years ago, my closest friend, who suffered from schizophrenia, took his own life. But my son, on the other hand, found his piece of sky, and escaped gloriously from the deep, in time becoming more like Carlyle than Caden. The sketches and drawings in

this book are his, all drawn in the depths. To me, there is no greater artwork in the world. In addition, some of Hal’s observations on life are derived from his poetry.

Our hope is that

Challenger Deep

will comfort those who have been there, letting them know that they are not alone. We also hope that it will help others to empathize, and to understand what it’s like to sail the dark, unpredictable waters of mental illness.

And when the abyss looks into you—and it will—may you look back unflinching.