Changing My Mind (33 page)

Authors: Zadie Smith

5

At about one in the morning, the young waiters, who have worked discreetly all night, now begin to approach: “I just wanted to say, I really dig your work. I think you’re totally amazing. Good luck on Sunday!” The actors, caught midway through conversations about their families, their dogs, a book they’ve read, a good restaurant in New York, now have to put their game face back on and become whoever it is the waiter thinks they are. They do this, for the most part, graciously. Confronted with such an embarrassment of riches, each waiter has chosen his virtual intimate to harass—that special actor who made him cry in the cinema, the singer whose tunes he plays when he clocks off work.

Outside the party the paparazzi have arrived. They do not have to chase anybody—there is nowhere to run. We are on a dark hillside in the middle of night. “And what would happen,” asks a rueful young director, “If an actor just stood out there all night? Took a photo from every possible angle, naked, told them every last thing they wanted to know. Would that be it? Would they be finished then?” It’s a long process; the huddle under heat lamps, the wait for cars. The actors themselves are relaxed about both the wait and the photographers outside; it’s their drivers who are anxious and defensive, projecting desires onto their charges that don’t seem to be there: “Can I get this guy out of the way for you? Shall I move him out of your face?” An actor goes out into the scrum and then comes back a minute later. “They don’t recognize me—I got fat for a role and now they don’t recognize me. I’m fasting now. Eight days so far.” To which comes the reply, “Me too! I just did five. Isn’t it

great!

”

6great!

”

A few of the nominees adjourn to Canter’s, a sprawling Jewish diner where you can get good chicken soup at two in the morning. I order one such soup with a matzo ball the size of my fist swimming in the center. The nominees order a plate of pickles and corned beef sandwiches; they drink beer and joke with a gang of teenage girls behind them. They talk about an actor’s distant family correction to the poet Wordsworth, about Hollywood, the house prices in Brooklyn and who has the largest fry on their plate. How to explain the fact that the same kinds of kids who on Sunday will scream their lungs out on the bleachers outside the Kodak Theatre are, right now, at two in the morning in Canter’s, sitting perfectly calmly while several globally famous actors eat home fries in the booth right next to them?

7On morning TV, some of the human beings from the night before are being described in Olympian terms by a pretty girl with a microphone. The detail is obsessive and alienating: what they might wear, eat and drink this coming Sunday is carefully itemized and salivated over; how they exercise, what they think about, whom they kiss, how they speak, where they go. The answers to these questions are all different, but one truth reigns: they are other. In relation to them, the only correct position is incomprehending awe. One cannot imagine their world, their ways.

I take my laptop out in an attempt to work by the water. A hot girl is loudly telling another hot girl that “

Brokeback

is so fucking awesome,” which is the consensus of the town, though little satisfaction can be drawn from this. That

Brokeback, Capote

and

Crash

are fucking awesome is neither here nor there for Hollywood: these films were all privately funded. This pool, like every pool in town, is now more frequently visited by excited young writers with laptops who have been cheered by the year’s “maverick” wave. This is the time for telling the world how Harpo Marx met Armand Hammer. Up in the hills the mood is less joyous. Strung up all over town are giant posters for Paramount’s new romantic comedy

Failure To Launch,

which is exactly the kind of underperforming, studio-made film that is causing the problem. These posters, with their airbrushed, smiling stars, flutter above the highway like the standards of a king who has been deposed, at least for this weekend.

8Brokeback

is so fucking awesome,” which is the consensus of the town, though little satisfaction can be drawn from this. That

Brokeback, Capote

and

Crash

are fucking awesome is neither here nor there for Hollywood: these films were all privately funded. This pool, like every pool in town, is now more frequently visited by excited young writers with laptops who have been cheered by the year’s “maverick” wave. This is the time for telling the world how Harpo Marx met Armand Hammer. Up in the hills the mood is less joyous. Strung up all over town are giant posters for Paramount’s new romantic comedy

Failure To Launch,

which is exactly the kind of underperforming, studio-made film that is causing the problem. These posters, with their airbrushed, smiling stars, flutter above the highway like the standards of a king who has been deposed, at least for this weekend.

Brunch with the nominated writers. Like everybody else, I have my Hollywood fantasy, and this it: a 1920s Spanish-style villa with original Mexican red and blue tiles in the fountain, with a living room Jimmy Stewart may have sat in once. It’s next to a golf course; every few years a ball breaks a window. The weather is darling: eggs and bacon and omelets are served in the courtyard. Being with writers instead of actors is like sitting in the pits instead of in the gods—one can speak freely, without fear. This is not their lives, but only an interlude. They make sure to tell you how they have kept their Manhattan apartments. Occasionally you meet a delusional Hollywood screenwriter who believes that without people like him there would be no movie business at all. Factually, of course, this is true—but it is delusional to draw any real conclusions from it. Scripts will be written, if need be, by fifteen people and the producer, or one million monkeys and a typewriter. Most screenwriters understand this and are wry about their Hollywood interludes. They are full of warnings and horror stories. “Do a first draft, but don’t touch it after that—unless you want your heart broken.” Or, alternatively, “Do the final polish, but that’s it. You’ll never write another novel if you get in too deep.” One writer nods and smiles encouragingly as some structural plans are outlined. “That’s very nice. But it doesn’t mean shit once an actor gets hold of it.” There is a campy relish for the Hollywood experience among the writers that is inaccessible to the “front-of-house” actors, who must live every day with the fantasies that are pressed upon them. “I weigh myself four times daily!” a man screeches, laughing as he says it. His companion wants to know if he has ever found that he weighs something different by the end of the day than he did at the start.

“Frequently!”

9Oscar morning arrives and it is impossible not to succumb to the thrill of the thing. A man comes to do my makeup. Here is his assessment of my dress: “If you were collecting the all-time queen of Hollywood lifetime achievement award, you would be overdressed.” A cocktail dress is substituted. At four o’clock in the afternoon, I get in a car and pick up two writers who are writing a film that actually has a shot at getting made. We are going to the

Vanity Fair

dinner at Morton’s to watch the ceremony on video screens, eat some great tuna and then wait for everybody to leave the Kodak Theatre and join us. The Oscar ceremony most resembles Christmas in its sense of anticlimax. Everyone was so excited earlier; now they are subdued, and grow more subdued as prizes are won and the potential web of alternative futures gets smaller and smaller, until there are only the people who won and everyone else who didn’t. There is a chorus of “Well, that’s just

hilarious

” from every table as the Oscar host makes his jokes, although few people actually laugh, and everyone is made tense by occasional jibes against individuals, studios or Hollywood itself. When it is over people seem relieved. The consensus is that it wasn’t as bad as it might have been. One girl text messages through the entire event.

Vanity Fair

dinner at Morton’s to watch the ceremony on video screens, eat some great tuna and then wait for everybody to leave the Kodak Theatre and join us. The Oscar ceremony most resembles Christmas in its sense of anticlimax. Everyone was so excited earlier; now they are subdued, and grow more subdued as prizes are won and the potential web of alternative futures gets smaller and smaller, until there are only the people who won and everyone else who didn’t. There is a chorus of “Well, that’s just

hilarious

” from every table as the Oscar host makes his jokes, although few people actually laugh, and everyone is made tense by occasional jibes against individuals, studios or Hollywood itself. When it is over people seem relieved. The consensus is that it wasn’t as bad as it might have been. One girl text messages through the entire event.

And then they come. We are told to vacate our tables and walk forward, where we will find Morton’s magically extended by the addition of a huge tarpaulin tent. At the mouth of the tent, the same TV girl with the microphone interviews the stars as they appear. Her MO is extreme naïveté: “What goes

on

in there?” she keeps asking, although she is as famous as many of the people inside and will soon join the party. “Can you just give us

some idea

of what kind of thing happens at a party like this?” Most of the invitees are at a loss to answer this question. An action star thinks about it and then indulges her: “It’s like Vegas: what goes on in there stays in there.” But “in there” there is only a charming, if tame, cocktail party, with a good deal of free booze and stilted conversation and a Porta-Potty. Everywhere people are trying to get introduced to other people, and feel glad when they are. These are melancholy victories, though. At a normal party we befriend people with the hope of seeing them again, of having a friendship, even a love affair. A “celebrity” encounter is more like a badge to be collected and then shown to other people. A whole night of collecting such badges grows demoralizing. You begin to understand the angry people you meet in Hollywood, who by choice or necessity regularly submit themselves to these one-way charm offensives, speaking with other human beings whom the world believes to be more than that. Yet there are people who seem to enjoy it; who work the room collecting all the badges and have no time to waste. At this party, a very short man who had been talking to a star and then, through a subtle shift in the circle, got stuck with me, actually asked to be released from his bondage. “Is it okay if I talk to someone else over there?”

on

in there?” she keeps asking, although she is as famous as many of the people inside and will soon join the party. “Can you just give us

some idea

of what kind of thing happens at a party like this?” Most of the invitees are at a loss to answer this question. An action star thinks about it and then indulges her: “It’s like Vegas: what goes on in there stays in there.” But “in there” there is only a charming, if tame, cocktail party, with a good deal of free booze and stilted conversation and a Porta-Potty. Everywhere people are trying to get introduced to other people, and feel glad when they are. These are melancholy victories, though. At a normal party we befriend people with the hope of seeing them again, of having a friendship, even a love affair. A “celebrity” encounter is more like a badge to be collected and then shown to other people. A whole night of collecting such badges grows demoralizing. You begin to understand the angry people you meet in Hollywood, who by choice or necessity regularly submit themselves to these one-way charm offensives, speaking with other human beings whom the world believes to be more than that. Yet there are people who seem to enjoy it; who work the room collecting all the badges and have no time to waste. At this party, a very short man who had been talking to a star and then, through a subtle shift in the circle, got stuck with me, actually asked to be released from his bondage. “Is it okay if I talk to someone else over there?”

This party is fun, all are beautiful, except for the old men who are powerful. People are drinking, finally, and the room is full of indiscreet conversation, much of it about where people will go next. Are you following the rappers with the thirty-thousand-dollar grills on their teeth and their newest accessory—a gold statuette in the palm? Or are you following the Frenchmen holding plush toy penguins above their heads? Committed badge collectors follow the whisper of the hope of an invitation up into the Hollywood Hills, in someone else’s car, with no clear idea of how they will get home.

Outside Morton’s, waiting for my car back to the hotel, I meet an old actor, a favorite of the late John Cassavetes, smoking a cigar and explaining how things are with him. “He chose me, you see?” he says of Cassevetes. “Me. It was a thing to be chosen by him, I can tell you that.” He is full of soul, and his eyes are rheumy and beautiful. “This town’s treated me well. I was never a star, no one knows my name, but I always worked, and now it’s given me a retirement plan. I’m the old dude in any movie you care to mention. Make nine or ten a year.” He smiled joyfully. We stood together on the forecourt with a lot of other people less joyful: losing nominees, yesterday’s news, TV stars, hungry models and people so famous they couldn’t get to their car without causing a riot. Of all the fantasies and dreams people have of a life in Hollywood, it seemed odd that no one had thought to dream a career like the one just described.

10The next day I woke at eight. In the name of research I watched an hour of fantasy television about the Oscars that in no way described the evening I had just had. I went back to sleep and woke at eleven. I checked out and dragged my hangover and my laptop down to the pool. It was empty. I ordered a quesadilla, but the speedy service that had been in place only yesterday had vanished. It took half an hour to get some Tabasco sauce. And then it began to rain, softly at first and then dramatically. I moved in under the glass roof and thought of nearby San Fernando Valley, where the American porn industry—a fantasy industry even larger and more remunerative than Hollywood—is located. The pool boys packed up the loungers around me. The rain drummed the surface of the pool and forced water over its edge, soaking the feet of the waitresses as they cleared the tables.

I packed up myself and went outside to wait for a cab. Three New York hipster kids ran into the hotel with their coats above their heads, one of them complaining: “It’s not supposed to

rain!

” The dream persists, even as reality asserts itself. I looked to my right and for the first time that weekend spotted someone I actually knew: Bret Easton Ellis. He asked what I was doing in L.A. and I told him. I asked what he was doing, and he looked at me with a kind of beatific insanity, as if he didn’t quite believe what he was about to say: “I’m moving back to L.A.!” I wanted to a share a novelist’s joke with him: what if you got assigned to write about the Oscars and you didn’t mention a single actor? You know, as a kind of demystifying strategy? How about that? But he had to get in his car. Anyway, Bret’s been there, done that: his own

Glamorama

tried another demystifying strategy, with fifty celebrities name-dropped in the first five pages. But the fantasies of fame cannot be dislodged by anyone’s pen. It’ll have to be a collective effort; we’ll have to wake from this dream together. It’ll be darling.

rain!

” The dream persists, even as reality asserts itself. I looked to my right and for the first time that weekend spotted someone I actually knew: Bret Easton Ellis. He asked what I was doing in L.A. and I told him. I asked what he was doing, and he looked at me with a kind of beatific insanity, as if he didn’t quite believe what he was about to say: “I’m moving back to L.A.!” I wanted to a share a novelist’s joke with him: what if you got assigned to write about the Oscars and you didn’t mention a single actor? You know, as a kind of demystifying strategy? How about that? But he had to get in his car. Anyway, Bret’s been there, done that: his own

Glamorama

tried another demystifying strategy, with fifty celebrities name-dropped in the first five pages. But the fantasies of fame cannot be dislodged by anyone’s pen. It’ll have to be a collective effort; we’ll have to wake from this dream together. It’ll be darling.

FEELING

Fourteen

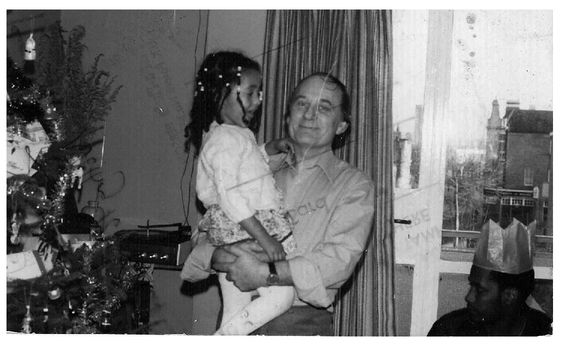

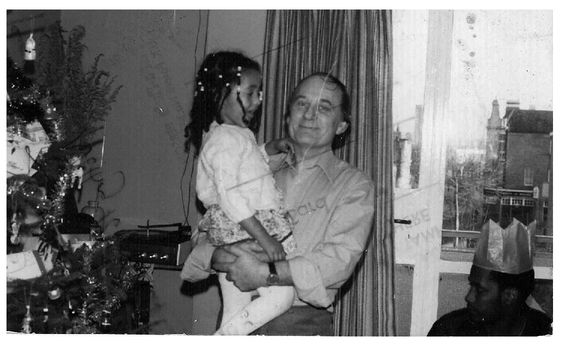

SMITH FAMILY CHRISTMAS

This is a picture of my father and me, Christmas 1980 or thereabouts. Across his chest and my bottom there is the faint pink, inverted watermark of postal instructions—something about a card, and then “stamp here.” Hanging from the tree like a decoration more mirror writing, this time from my own pen. Does it say

Nothing

? Or maybe

Letting

? I’ve ruined this photo. I don’t understand why I can’t take better care of things like this. It’s an original, I have no negative, yet I allowed it to sit for months in a pile of mail on my open windowsill. Finally the photo got soaked, imprinted with the text of phone bills and Post-it notes. I felt sick wedging it inside my

OED

to stop the curling. But I also felt the weird relief that comes from knowing that the inevitable destruction of precious things, though done in your house, was not done by your hand. Christmas, childhood, the past, families, fathers, regret of all kinds—no one wants to be the grinch who steals these things, but you leave the door open with the hope he might come in and relieve you of your heavy stuff. Christmas is heavy.

Nothing

? Or maybe

Letting

? I’ve ruined this photo. I don’t understand why I can’t take better care of things like this. It’s an original, I have no negative, yet I allowed it to sit for months in a pile of mail on my open windowsill. Finally the photo got soaked, imprinted with the text of phone bills and Post-it notes. I felt sick wedging it inside my

OED

to stop the curling. But I also felt the weird relief that comes from knowing that the inevitable destruction of precious things, though done in your house, was not done by your hand. Christmas, childhood, the past, families, fathers, regret of all kinds—no one wants to be the grinch who steals these things, but you leave the door open with the hope he might come in and relieve you of your heavy stuff. Christmas is heavy.

Other books

Undocumented : How Immigration Became Illegal (9780807001684) by Chomsky, Aviva

Dead Secret by Janice Frost

Full Heat: A Brothers of Mayhem Novel by Carla Swafford

The Little Sister by Raymond Chandler

Flirting with Texas (Deep in the Heart of Texas) by Lane, Katie

Somewhere! (Hunaak!) by Abbas, Ibraheem, Bahjatt, Yasser

Mage Catalyst by George, Christopher

The Woman of Andros and The Ides of March by Wilder, Thornton

No Escape From Destiny by Dean, Kasey

A History of China by Morris Rossabi