Authors: Howard Sounes

Charles Bukowski (10 page)

When Corrington started telling Bukowski what his English Dean had said on the subject of James Joyce, he couldn’t stand any more. ‘Fuck your Dean,’ he said.

Corrington was deeply offended, but Bukowski was not about to apologize and began sneering at everything Corrington said, especially when he tried to talk about Republican politician Barry Goldwater, saying he was a good man. They were at loggerheads

now, too stubborn to back off and decided to pout at each other throughout the rest of the evening. Miller Williams believes Bukowski was chiefly at fault. ‘It was the kind of self-destructive defensiveness that an early adolescent will engage in,’ he says. ‘Corrington was very hurt that he had been rejected by someone whose work was important to him and whose approval he very much wanted.’ It was the end of their friendship.

With a relatively large print run and New York publisher, Lyle Stuart, handling distribution,

Crucifix in a Deathhand

was the biggest book of Bukowski’s career to date, and the Webbs did another beautiful design job. Printed in a large format, and illustrated with nightmarish etchings by Noel Rockmore, it looked like an album of Gothic fairy tales. But with the benefit of hindsight, Bukowski was correct to fear his poetry would be compromised by writing under pressure.

In his more honest moments, he admitted he had slipped. He knew Webb wanted better, but he could not produce poems to match the standard of the first book. Jon Webb reported that Henry Miller was enthusiastic, but when Bukowski wrote to Miller, whom he admired and whose book

Tropic of Cancer

has much in common with his own later novels, suggesting they get together, Miller declined and scolded Bukowski for drinking too much. He said it was a sure way to kill inspiration.

There were notable poems in the book, however, few better than ‘something for the touts, the nuns, the grocery clerks and you …’. This was virtually a polemic against capitalism, although Bukowski maintained he was not a political writer. ‘I am not a man who looks for solutions in God or politics,’ he said. He did not align himself with the Left – although FrancEyE remembers him expressing admiration for Communist Dorothy Healey – any more than his college flirtation with Nazism had matured into a sympathy with the Right. At the same time some of the poems in

Crucifix in a Deathhand

, and later work like

Factotum

, show an interest in the problems of the urban under class. ‘What I’ve tried to do, if you’ll pardon me, is bring in the factory-workers aspect of life,’ he said. ‘The screaming wife when he comes home from work. The basic realities of the everyman existence … something seldom mentioned in the poetry of the centuries. Just put me down

as saying that the poetry of the centuries is shit. It’s shameful.’ He achieved his goal in ‘something for the touts, the nuns, the grocery clerks and you …’ without political posturing.

… the days of

the bosses, yellow men

with bad breath and big feet, men

who look like frogs, hyenas, men who walk

as if melody had never been invented, men

who think it is intelligent to hire and fire and

profit, men with expensive wives they possess

like 60 acres of ground to be drilled

or shown-off or to be walled away from

the incompetent, men who’d kill you

because they’re crazy and justify it because

it’s the law, men who stand in front of

windows 30 feet wide and see nothing,

men with luxury yachts who can sail around

the world and yet never get out of their vest

pockets, men like snails, men like eels, men

like slugs, and not as good …

and nothing. getting your last paycheck

at a harbor, at a factory, at a hospital, at an

aircraft plant, at a penny arcade, at a

barbershop, at a job you didn’t want

anyway.

income tax, sickness, servility, broken

arms, broken heads – all the stuffing

come out like an old pillow.

By this stage in his career, his work was familiar to the readers of practically every small literary magazine in America, and a good many in Europe. Well-produced if obscure books like those made by the Webbs enhanced his reputation and many young poets began to look to him as a leader. One of these was Douglas Blazek, a Chicago poet and foundry worker who produced his own little magazine,

Ole

, on a $100 Sears & Roebuck mimeograph machine.

This sort of primitive technology was responsible for the sloppy appearance of most little magazines, but in Blazek’s case it was in keeping with the gritty nature of the work.

When Blazek discovered Bukowski had written short stories, back in the ’40s, he asked for some prose for

Ole

and Bukowski responded with a breakthrough piece,

A Rambling Essay On

Poetics And The Bleeding Life Written While Drinking A Six

Pack (Tall)

. It was meant as an essay, more than a short story, a statement of his literary beliefs, but what came across most strongly was that he was writing about himself.

He wrote that his father was a ‘monster who bastardized me upon this sad earth’, thus fostering the abiding myth he was illegitimate; and he invited his readers to call him ‘uncultured, drunken, whatever’ as if he were a Philistine. The message was that Bukowski had ‘crawled drunken in alleys from coast to coast’ and the poetry that came from these experiences was all the more powerful for it.

‘Being the age that I was, I had my mouth wide open and I was swallowing it all,’ says Blazek. Many of those who read the essay in

Ole

also took it as a true account of Bukowski’s life and wanted to know more about the poet who said he had shouldered carcasses in a slaughter house (in fact, he worked half a day in a slaughter house on one occasion during his supposed ten-year drunk).

When he got back to De Longpre, after visiting the Webbs, Bukowski found he had fan mail and wrote Blazek on 17 April, 1965: ‘I get these letters on the essay I wrote for

Ole

2 and they seem to think I said something; I am a fucking oracle (oriol?) for the LOST or something, is what they tell me. that’s nice. but I AM THE LOST.’

Blazek went on to publish a Bukowski chapbook of a single prose piece,

Confessions of a Man Insane Enough to Live with

Beasts

, a portmanteau of nine short stories based on his childhood, adolescence and youth. It further promoted Bukowski as the hero of his own work, even though he used the device of a fictional first-person narrator. The name, Henry Chinaski, was noticeably similar to his own.

‘

Confessions

became a dry run for his first novel,

Post Office

, and from then on I think he duplicated himself,’ says Blazek. ‘

Ham

FAMILY HISTORY

Bukowski’s maternal grandparents Nanatte and Wilhelm Fett (seated) celebrate their golden wedding anniversary with family and friends in Andernach, Germany, in 1943.

(courtesy of Karl Fett)

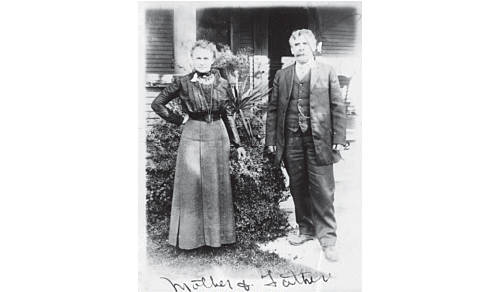

Charles Bukowski’s paternal grandparents Emilie and Leonard Bukowski at their home in Pasadena, California.

(courtesy of Katherine Wood)

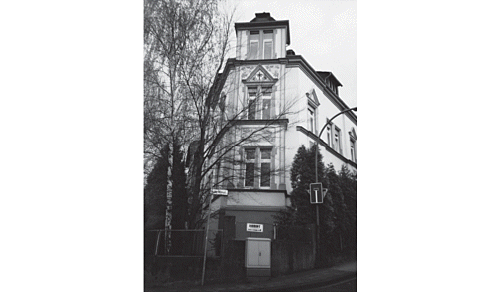

Bukowski’s parents lived in an apartment in this building in Andernach, Germany, when they were fi rst married and Bukowski was born here on 16 Aug, 1920. The window on the second fl oor under the cross is the room in which he was born.

(picture taken by Howard Sounes)

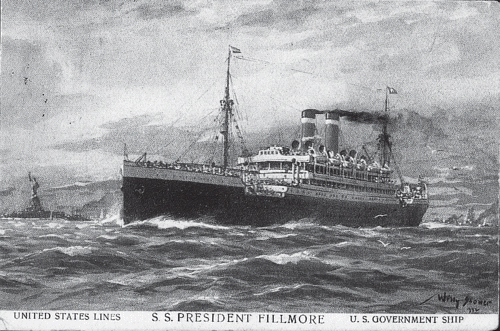

COMIGN TO AMERICA

This is the postcard Bukowski’s mother sent to her parents from the docks at Bremerhaven, Germany, on 18 April, 1923, just before she and Henry Bukowski and their son sailed for America. It shows the SS President Fillmore, the ship which took them to Baltimore.

(courtesy of Karl Fett)

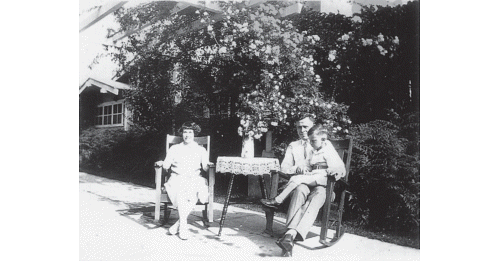

In 1924 Bukowski’s mother sent this photograph of herself, her husband and their son from her mother-in law’s house in Pasadena, California, to her parents in Andernach, writing that Henry had won an argument about who should hold their son for the picture.

(courtesy of Karl Fett)

The infant Bukowski looks thoroughly glum on a day out with his parents at Santa Monica beach, California. Kate Bukowski wrote to her parents in Germany that Henry wanted her to send photographs of them at the beach to prove he was showing them a good time in America.

(courtesy of Karl Fett)