Charles Bukowski (13 page)

Authors: Howard Sounes

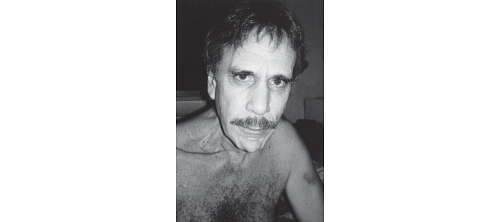

Poet Steve Richmond, a close friend for many years who thought Bukowski’s attitude to drugs hypocritical.

(picture

taken by Howard Sounes)

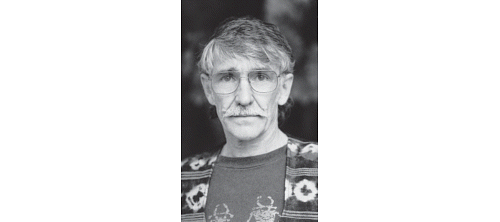

John Bennett, small press publisher and friend of Bukowski’s.

(courtesy

of John Bennett/photo credit:

Jane Orleman)

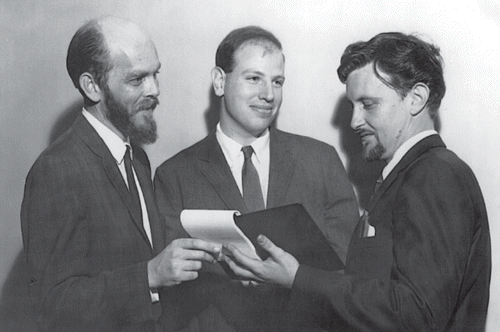

The writer and academic John William Corrington (far right) who had a long and warm correspondence with Bukowski until they met at the home of Jon and ‘Gypsy Lou’ Webb in New Orleans and fell out. On the left is Miller Williams who was also at the meeting.

(courtesy of Joyce Corrington)

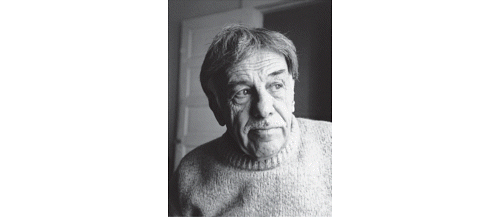

Beat poet and gay writer Harold Norse who controversially claims Bukowski fl ashed his penis at him and asked to see Norse’s penis in return.

(picture taken by Howard Sounes)

German-born photographer Michael Montfort who accompanied Linda Lee and Bukowski on their fi rst trip to Europe in 1978.

(taken

by Howard Sounes)

Bukowski with his publisher and friend Jon Webb.

(courtesy of ‘Gypsy Lou’ Webb)

Bukowski and ‘Gypsy Lou’ Webb at Bukowski’s bungalow in Hollywood in August, 1964, when the Webbs came to check him out.

(courtesy of ‘Gypsy Lou’ Webb)

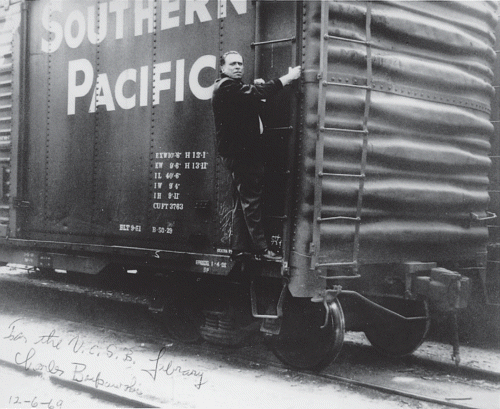

Bukowski wanted to be photographed in a tough guy pose for his 1969 book,

The Days Run Away

Like Wild Horses Over the Hills

, so photographer friend Sam Cherry took this picture of Bukowski clinging onto a boxcar in downtown LA. Bukowski was so fat and lacking in agility he almost fell off.

(courtesy of Sam Cherry)

on Rye

, all of that, was regurgitated. All his previous stuff was just a dry run for the more substantial works that John Martin published at Black Sparrow Press.’

It is true that many of the stories that later became significant parts of his novels first appeared in these short stories. For example, Bukowski first wrote about Jane Cooney Baker in

Confessions

of a Man Insane Enough to Live with Beasts

. He introduced her as K:

K. was an ex-showgirl and she used to show me the clippings and photos. She’d almost won a Miss America contest. I met her in an Alvarado St. bar, which is about as close to getting to Skid Row as you can get. She had put on weight and age but there was still some sign of a figure, some class, but just a hint and little more. We’d both had it. Neither of us worked and how we made it I’ll never know …

Ten years later he wrote about her in his novel,

Factotum

, but it was essentially the same thing:

I found myself on Alvarado Street. I walked along until I came to an inviting bar and went in. It was crowded. There was only one seat left at the bar. I sat in it. I ordered a scotch and water. To my right sat a rather dark blonde, gone a bit to fat, neck and cheeks now flabby, obviously a drunk; but there was a certain lingering beauty to her features, and her body still looked firm and young and well-shaped. In fact, her legs were long and lovely.

Both versions show how much he manipulated the facts of Jane’s life to make a story.

Even though FrancEyE wanted him to do things with her and Marina, Bukowski’s weekends were still mostly taken up with drinking. He stumbled around the bars, getting into fights and sometimes getting himself locked up. When he stayed home, he emptied beer bottles by the half dozen, clanging empties into the garbage until neighbors yelled for him to shut up, or singing songs

from

Oklahoma!

with Francis and Grace Crotty at the back of the court. Alcohol was so much a part of daily life that the first word Marina learned to read was ‘liquor’ and she came to know Ned’s liquor store as ‘Hank’s Store’ because her father spent so much time there.

One night around Thanksgiving, 1965, Bukowski came home from the post office, got a beer from the refrigerator, and told FrancEyE it wasn’t working.

‘You have to get out of here,’ he said.

He promised to help her find a place where she could live with Marina, and said he would continue to support them. ‘He hated having an unhappy woman around, and he knew how unhappy I was,’ says FrancEyE, who had been thinking of moving out anyway.

Marina believes she is lucky the split came before she knew any other life. ‘I didn’t have any unhappy memories of that and, obviously, if it had been a year or two later I would have been at least initially miserable,’ she says. ‘How my father raised me and how my mother raised me was pretty unconventional, just the fact that they weren’t together was one piece of the puzzle, but I always felt a really strong connection to him. He let me know both by his actions and his words that he loved me more than anything, so I always took that for granted as a child. It is something that is so basic and so important and it just made everything in the world OK.’

Despite his many problems, and his drinking, FrancEyE found she could rely on Bukowski even after they split. ‘I could never handle money,’ she says. ‘My money would run out and we would be out of food. Whenever I called Hank, and said, “Can we come over and eat?” Or, we need this or that, he was always right there.’

But when she had time to reflect on their relationship as a couple, FrancEyE did not come to an entirely positive conclusion. She was especially hurt when some of Bukowski’s letters were published in the early 1990s, revealing how little he had understood her, and how he often belittled her in correspondence with his friends.

In response, FrancEyE wrote the poem, ‘Christ I feel shitty’:

At least it’s clear now

He hated me

for being somebody I never was.

Maybe I loved him

for the same reason.

I thought he would want to hear amazing stories

when all he wanted was somebody to clean up the kitchen,

just like he said all along.

I

t is one of the ironies of Bukowski’s career that his eventual success was largely due to the hard work of a Christian Scientist who drinks nothing stronger than iced tea. John Martin was the manager of an office supply company when he first read Bukowski’s poetry, and it literally changed his life. He decided Bukowski was a great genius, ‘the Walt Whitman of our day’, and set out to become his publisher.

First he read all the books that were available. He bought

It Catches my Heart in Its Hands

and, through Jon Webb, got an inscribed copy of

Crucifix in a Deathhand

. Then, in October, 1965, he wrote to Bukowski asking to buy signed copies of the early chapbooks, adding that he thought Bukowski was ‘a most important and marvellous poet’. Bukowski sent him a copy of

Confessions of a Man Insane Enough to Live

with Beasts

, and Martin wrote again ten days later, saying he wanted to invite him to lunch, adding: ‘I’ve never had the pleasure of talking to a really fine poet.’ Bukowski postponed the meeting while he found a place for FrancEyE and Marina to live, but invited Martin over to De Longpre after he wrote again in January saying he’d been given bottles of liquor for Christmas, but didn’t drink, and wondered if Bukowski wanted them.

Bukowski was drinking beer when he looked up and saw a smartly dressed gentleman on his porch. His visitor had wisps

of reddish hair around a mostly bald head, although he was still young, and was grinning broadly.

‘I’ve always been a great admirer of your work,’ said John Martin, introducing himself. ‘I’d like to come in.’

‘Oh well, come on in. Want a beer?’

Martin declined, reminding Bukowski that he didn’t drink. ‘That kind of put me off right there: this guy’s inhuman, he doesn’t drink beer!’ said Bukowski, recalling the meeting.

For his part, Martin was taken aback by Bukowski’s scruffy appearance and the filthy conditions he was living in, now FrancEyE had left. ‘He had this absolutely destroyed room,’ he says. There were rusty razor blades round the sink, the toilet didn’t flush properly and the work surfaces were covered dust and bits of food.

Martin asked if he had any writing he could look at, and Bukowski told him to look in the closet.

‘What’s this?’ asked Martin, looking at a stack of paper that reached up almost to his waist.

‘Writing,’ replied Bukowski.

‘No kidding?’

‘Yeah.’

‘How long it take you to write this?’

‘Oh, I don’t know, three or four months.’

‘Oh, this is astonishing. You mind if I read it?’

‘Go ahead.’

Bukowski cracked open another beer while his visitor began wading through the mass of paper. There were countless poems and short stories, and most of it had never been published. It was such a treasure trove Martin could barely contain his excitement.

‘Oh this is very good!’ he exclaimed. ‘This is great!’ Another gem revealed itself. ‘This is an immortal poem!’

‘Oh yeah?’ drawled Bukowski.

After what seemed a long time, Martin stopped reading and said he was thinking of starting a small press. He would like to take three or four of the poems with him, look them over at home, and maybe print them up as broadsides. ‘There’ll probably be some money in it for you. I don’t know how much.

We’ll have to see,’ he said. Bukowski shrugged and said he could go ahead. Hell, he’d put his hand in his own pocket to help editors publish his work. The Webbs had paid him in kind with copies of the books. To get paid money would be something new.

Apart from being a successful businessman, John Martin was a serious book collector who had an impressive library of first editions. It was his interest in D.H.Lawrence that led him to read about the career of B.W.Huebsch, founder of Viking and Lawrence’s American publisher. He discovered Huebsch had started out by publishing writers who were not yet established, and Viking grew as they became more successful. It dawned on Martin that many of his favorite writers, including Bukowski, had been ignored by the New York publishers. He also wanted to work with his wife, Barbara, in the way Harry and Caresse Crosby had worked together on the Black Sun Press. Inspired by the example of Huebsch, the Crosbys, and by a William Carlos Williams poem about a sparrow, he decided to launch Black Sparrow Press. ‘I liked the combination of the e´lite black and very common sparrow,’ he says, explaining the name.

He selected five of the poems from the bundle he had taken from Bukowski’s closet and decided to print thirty copies of each, twenty-seven numbered and three lettered: A, B, and C, for author, publisher and the press operator at work who had agreed to print them up.

The first poem was ‘True Story’, which concerns a man who has castrated himself. Martin says he chose it because ‘it’s a pretty grim poem and it just struck me as being very existential.’

they found him walking along the freeway

all red in

front

he had taken a rusty tin can

and cut off his sexual

machinery

as if to say–

see what you’ve done to

me? you might as well have the

rest.

In March, 1966, Bukowski went into hospital to have his haemorrhoids removed. He took time off work afterwards and wrote a hilarious account of the operation,

All the Assholes in

the World and Mine

, which was published by Douglas Blazek. He was still off work in April when John Martin brought the first Black Sparrow broadsides over to be signed. He also gave Bukowski a check for $25. It was money he badly needed because his post office sick pay had run out, his medical insurance didn’t cover the hospital bills, and the child support was due.

Bukowski and Martin were very different personalities, but their differences worked to their advantage, forming the basis of a long and happy association. Once Bukowski came to terms with dealing with a teetotaller, although he never wholly understood it (what did Martin do if he didn’t drink?) he trusted him more than a fellow drinker. ‘He knew I’d never make a drunken stupid move, make a deal I shouldn’t make,’ says Martin. And although Martin is an astute businessman, Bukowski realized he was far from being conventional, and that he really did appreciate the work. Mutual friend and poet, Gerard Malanga, describes Martin as a paradox: ‘He is kind of a straight guy in a funny way, but he is very hip. You can be straight and hip.’

Both men were pleased with the way the broadsides turned out and almost right away Martin decided to try and publish books. He sold his collection of first editions to the University of California at Santa Barbara and used the $50,000 he raised to build Black Sparrow into a company that could publish Bukowski and other new or neglected writers. He was soon bringing out broadsides and chapbooks as striking in the simplicity of their design as the Loujon books were ornate.

Barbara Martin was responsible for the distinctive Black Sparrow artwork. Her use of classic typography, with plain rules, turned out to be the perfect complement to Bukowski’s pared-down poems, work like ‘a little atomic bomb’ which they published in a chapbook called, simply,

2 Poems

:

o, just give me a little atomic bomb

not too much

just a little

enough to kill a horse in the street

but there aren’t any horses in the street

well, enough to knock the flowers from a bowl

but I don’t see any

flowers in a

bowl

enough then

to frighten my love

but I don’t have any

love

well

give me an atomic bomb then

to scrub in my bathtub

like a dirty and lovable child

(I’ve got a bathtub)

just a little bomb, general,

with pugnose

pink ears

smelling like underclothes in

July

The best of Bukowski’s mature poetry was written in this minimalist style, although it is not to everyone’s taste. ‘Bukowski’s poetry was essentially stories, just like his prose,’ says Lawrence Ferlinghetti. ‘It just happened some days that he didn’t get the carriage of the typewriter to the end of the line. Depends how badly hungover he was when he started to type.’ But Bukowski was achieving the trick he’d been trying to pull off since his twenties. Inspired by the direct prose style of John Fante and Ernest Hemingway, and more recently by the poetry of Pablo Neruda, Robinson Jeffers and others, he was ‘writing down one simple line after another’ and bringing humor in as well, because he believed

‘creation cannot be all that serious, or you fall asleep.’ John Martin loved the work and saw Bukowski as a totally original voice.

‘When I started Black Sparrow, I was publishing guys who thought they were French symbolists. I was publishing guys who thought they were surrealists, and you had to sit and work with the poems to get the meaning,’ he says. ‘Then here comes this voice out of nowhere and you have no doubt what he means, and what he is trying to say.’

Bukowski liked to mock the counter-culture, having little time for drugs, pop, music or radical politics. But many of the young writers and publishers who liked his work were deeply involved in these things and Bukowski was inevitably drawn into what was happening in the late 1960s.

Another of his new admirers was a student called Steve Richmond whose wealthy family had set him up in a cottage by the ocean at Santa Monica. He studied law at the University of California, but spent most of his time getting laid, dropping LSD with his buddy Jim Morrison, and writing poetry about the amazing things going on in his head. What really freaked Richmond out was reading Bukowski’s poems in

Ole

magazine. Like John Martin, but in a spacier way, he decided Bukowski was ‘a genius of the world’ and made a pilgrimage to De Longpre Avenue to meet his hero. Bukowski made such an impression on him that he abandoned his plans to become a lawyer and opened a poetry book shop where he sold Bukowski chapbooks.

Flattered by the attention, Bukowski began hanging out at Earth Books, where he cut a very different figure from Richmond and his hippy friends. Bukowski’s hair was very short and slicked back. His nose was red with broken veins. He wore short-sleeve button-down shirts, the neck open to reveal a triangle of white T-shirt. On his feet were brown or black lace-up shoes, ‘post office shoes’ as Richmond called them, and he wore a shapeless sports jacket if it were cold.

He was usually toting a brown paper bag containing two six-packs of beer. Everybody else was smoking dope and dropping acid, which didn’t impress Bukowski at all. ‘Bukowski thought it was so phony,’ says Richmond. ‘Timothy Leary and the hippies. He was right in a way.’

In a letter to Richmond, Bukowski wrote: ‘LSD, yeah, the big parade – everybody’s doin’ it now. Take LSD, then you are a poet, an intellectual. What a sick mob. I am building a machine gun in my closet now to take out as many of them as I can before they get me.’

The hippies who drifted into the store, off Ocean Park Boulevard, generally liked Bukowski’s work. But if they had read his latest chapbook,

The Genius of The Crowd

, they would have seen that, although he was against many of the conventions of society, he was not for the counter-culture either:

… The Best At Murder Are Those

Who Preach Against It

AND The Best At Hate Are Those

Who Preach LOVE

AND THE BEST AT WAR

FINALLY ARE THOSE WHO PREACH

PEACE

Richmond was inspired to publish a selection of poems by Bukowski, and himself, in a radical new magazine which he called

The Earth Rose

. The page one headline read:

HATE

This was followed by a sub-heading:

Whereby, on this day we able minded creators do hereby tell you, the Establishment: FUCK YOU IN THE MOUTH. WE’VE HEARD ENOUGH OF YOUR BULLSHIT.

The cops arrested Richmond for obscenity, and seized his stock, including many of Bukowski’s books.

After taking his first acid trip in 1962, John Bryan quit his job with the Hearst Corporation in San Francisco and moved to LA to spread the good news about LSD. ‘We were into acid evangelism.

We thought we could save the world by getting everybody high on psychedelics,’ he says. ‘For a while we almost did it.’ He rented a house in Hollywood and started printing a magazine called

Notes

from Underground

which provided formulas for making LSD.

Bukowski contributed poems to Bryan’s magazine and, through this association, met other poets and publishers who were deeply into drugs, like the writer John Thomas.

*

Bukowski got into the habit of dropping by Thomas’ house after finishing his graveyard shift and would sit up half the night talking about his problems at the post office, and his hassles with FrancEyE, while Thomas guzzled amphetamines which he was addicted to.

Bukowski said FrancEyE had become swept up in the idealism of the hippies and was dragging Marina along to peace marches and other protest events which he believed she was far too young for. He worried Marina might get hurt. He was also exasperated by FrancEyE’s inability to manage her money, finding her so irritating he could no longer bring himself to use her name, referring to her laconically as ‘the mother of my child’. He also complained at length about not getting laid.