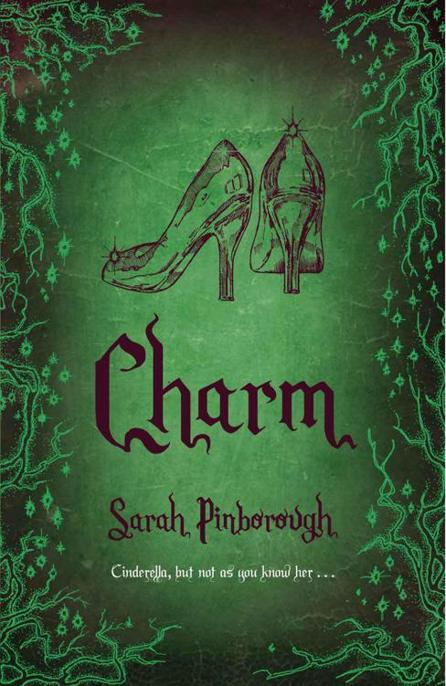

Charm

For Phyllis, Di and Lindy

2 ‘He’s a cheeky little fella, this one’

7 ‘He was so very beautiful . . .’

10 ‘She’d finish it once and for all . . .’

11 ‘I can take care of myself . . .’

12 ‘There has to be a wedding . . .’

13 ‘Of course it’s love . . .’

‘Once upon a time . . .’

W

inter had come early. Its fierce breath tore the leaves from the trees before they had even turned crisp and golden, and although the New Year was still a month away the cityscape had been white for several weeks. Frost sparkled on window panes and the ground, especially at the cusp of dawn, was slippery underfoot. Only on those days when the sky turned clear blue, in a moment’s respite from the grey that hung like a pall across the kingdom, could the peak of the Far Mountain be seen. But no one would really look for it until spring. Winter had come, and its freezing grip would keep the people’s heads down until the ice melted. This was not the season for adventure or exploration.

As was the way with all the kingdoms, the forest lay between the city and the mountain. It was a sea of white under a canopy of snow and, beyond the grasping skeletons of the weather-beaten trees at its edge, it was still dense and dark. From time to time, on quiet nights, the cries of the winter wolves could be heard as they called to each other in the hunt.

The man kept his head down and his scarf pulled up over his nose as he moved from post to post, nailing the sheets of paper to the cold wood. It had been a particularly bitter night, and even though it was drawing close to breakfast time the air was still mid-night blue. His breath poured so crystalline from his lungs that he could almost believe it was fairy dust. He hurried from one street lamp to the next eager to be done and home and by a warm fire.

He paused at the end of the street of houses and pulled a sheet of paper from the now mercifully small bundle tucked beneath his arm and began nailing it to the post. Residents would send their maids – for although these houses lacked the grandeur of those nearer the castle they were still respectably middle-class, home to the heart of the city: the merchants and traders who kept the populace employed and alive – to discover what news there might be of the ordinary people. It wouldn’t be spoken of when the criers came later to share news from the court.

Although he wore woollen gloves they were cut off at the knuckles to give his fingers dexterity, but after two hours in the cold the tips of his fingers were red and raw and clumsy. With the nail between his teeth he pulled the small hammer from his pocket but it tumbled to the ground. He cursed, muttering the words under his breath, and leaned forward, his back creaking, to pick it up.

‘I’ll get that for you.’

He turned, startled, to find a man in a battered crimson coat standing there. He had a heavy knapsack on his back and his boots were muddy and worn. He wore no scarf, but neither did he seem particularly bothered by the cold that consumed the city, despite the chapped patches on his cheeks. As the stranger crouched, the tip of a spindle was visible poking out of the heavy bag across his back.

‘Thank ‘ee.’

The stranger watched as he nailed the paper down, his eyes scanning the information there.

Child missing.

Lila the Miller’s daughter.

Ten years old. Blonde hair. Checked dress.

Last seen two days ago going for wood in the forest.

‘That happen a lot?’ The stranger’s voice was light, softer than expected from his worn exterior.

‘More than ought to, I suppose.’ He didn’t want to say too much. A city’s secrets should stay its own. He sniffed. ‘Easy for a child to get lost in a forest.’

‘Easy for a forest to lose a child,’ the stranger countered, gently. ‘The forest moves when it wants, haven’t you noticed? And it can spin you in a different direction and send you wherever it decides best.’

The man turned to look at the stranger again, more thoughtfully this time. The wisdom in his old bones told him that there were secrets and stories hidden in the weaver; perhaps some that never should be told, for once a story was told it could not be untold. ‘If it’s a man that’s done it, then he’ll take the Troll Road when they catch him, that’s for sure.’

‘The Troll Road?’ The stranger’s eyes narrowed. ‘That doesn’t sound like a good place.’

‘Let’s hope neither of us ever finds out.’

The barb of suspicion in the man’s voice must have been clear, because the stranger smiled, his teeth so white and even they hinted at a life that was once much better than this one, and his eyes warmed. ‘I did not see any children in the forest,’ he said. ‘If I had, I’d have sent them home.’

‘Have you come far?’ The man asked, putting his hammer back in his pocket.

‘I’m just passing through.’

It wasn’t an answer to the question, but it seemed to suffice and the two men nodded their farewells. Tired as he was, and with his nose starting to run again, he watched the stranger wander up the street with his spindle on his back. The stranger didn’t look back but continued his walk at a steady, even pace as if it were a warm summer’s afternoon. The man watched him until he’d disappeared around the corner and then shivered. While he’d stood still the cold had crept under his clothes like a wraith and wormed its way into his bones. He was suddenly exhausted. It was time to go home.

Around him the houses were slowly coming to life, curtains being drawn open like bleary eyelids and here and there lamps flickered on, mainly downstairs where fires were being prepared and breakfasts of hot porridge made. As if on cue, a door bolt was pulled back and a slim girl wrapped in a coat hurried out of a doorway and crouched beside the coal box with a bucket. Even in the gloom he could see that her long hair was a rich red; autumn leaves and dying sunsets caught in every curl.

The metal scraped loudly as she pulled the last coals from the bottom, the small shovel reaching for the tiniest broken pieces that might be hiding in the corners of the scuttle. There was barely enough in that bucket for one fire, and not a big one, the man reckoned. The girl would be going to the forest to fetch wood soon enough, missing children or not.

As she got to her feet their eyes met briefly and she gave him a half-smile in return to his tug on his cap. He turned and headed on his way. He still had five notices to pin up and a smile from a pretty girl would only warm him for part way of that.

C

inderella was back in the house and clearing the ashes from the dining room fireplace when Rose came down in her thick dressing gown, her hands shoved deep in the pockets. Cinderella was dressed but she still hadn’t taken her coat off. The house wasn’t that much warmer than it was outside, and if they didn’t start having fires in more than one room soon, she’d be spending her mornings scraping ice from the top of the milk and the morning washing bowls as well as doing all the other chores that had crept up on her over recent months, since Ivy’s romance and wedding.

‘It’s getting colder,’ Rose said. Cinderella didn’t answer as her sister – her

step

-sister – pulled open the shutters and lit the lamp on the wall, keeping it down so low to preserve oil that it barely dispelled the darkness.

‘So, what’s the news?’

‘What do you mean?’ Cinderella finally looked up, her bucket of ashes full.

‘I saw you reading the

Morning Post

,’ Rose said, nodding towards the wooden post with the sheet of paper nailed to it and fluttering like a hooked fish in the sea of the rising winter wind.

‘Another missing child. A little girl.’ She got up and dusted her coat down. The new fire still needed to be laid but she’d forgotten to bring the kindling up from the kitchen with her. She’d sit for five minutes by the stove and get warm first.

‘Something needs to be done about whatever’s in the woods,’ Rose muttered. ‘We can’t keep losing children. And the forest is the city’s life blood. The more people fear going into it, the weaker the kingdom becomes.’

‘Might just be winter wolves.’

‘A sudden plague of them?’ Rose’s sarcasm was clear in both her tone of voice and the flashed look she sent Cinderella’s way. ‘It’s not wolves. They can be vicious but not like this. And, without being indelicate, if it were wolves, at least some remains would be found. These children are disappearing entirely.’

‘Maybe they’ll turn up.’ Cinderella was tired enough without having to listen to another of Rose’s rants. She’d already put the porridge on, put the risen bread in the oven and after breakfast she’d have to peel the potatoes and vegetables before even having a wash.

‘Of course they won’t. And then we’ll have a whole generation growing up scared to go into the woods and a society even more fuelled by suspicion. If the king doesn’t act soon he’s going to find the people losing their love for him. A visible presence of soldiers or guards at the forest’s edge is what he needs. At the very least.’

Tight lines had formed around her mouth and between her eyes and Cinderella thought they made Rose look older than her twenty-five years. Rose’s hair was fine and poker straight, the sort of hair that could never hold a curl for long, no matter how much lacquer was applied or how long the rollers were in, and although her features were regular enough there was nothing striking or unusual about them. She was, if the truth were to be told, a plain girl. Neither Rose nor her sister Ivy had ever been pretty. They might have come from money, but it was Cinderella who had the looks.

‘Breakfast will be done in a minute.’ She tucked a thick red curl behind one ear and picked up the bucket of ash. ‘As soon as I’ve got this cleared away.’

‘I’d help,’ Rose said. ‘But mother says I have to keep my hands soft.’

‘Will take more than soft hands to get you wed,’ Cinderella muttered under her breath as she headed for the door.

‘What did you say?’

‘A mouse!’ The shriek was so loud and unexpected that Cinderella, whose arms were aching, jumped and dropped the bucket of ash, mainly down her own coat. ‘There’s a mouse!’ her step-mother shrieked again, appearing in the doorway, her face pale and her hair still in rollers and firmly under a net from the night before. ‘It’s gone down to the kitchen! We can’t have a mouse. Not here. Not now. Not with Ivy coming!’

‘What is going on here today?’ She stared in dismay at the cloud of ash that was settling across the floor and surfaces of her pride and joy, her dining room. ‘Oh, Cinderella, we don’t have time for this. Get it cleaned up. I want this place spotless by nine.’ She turned to bustle away and then paused. ‘No, I want it spotless by eight. And Rose, once you’ve had breakfast it’s time for a facial and manicure. There’s a girl coming at half-past nine. Highly recommended.’

Cinderella looked down at her own chapped hands. ‘I wouldn’t mind a manicure.’

‘Don’t be so ridiculous,’ her step-mother snapped. ‘Why would you need one? Rose is the daughter of an Earl. People are beginning to remember that. And anyway, they’re expensive, we can only afford one. Now come on, I want everything perfect for Ivy and the Viscount.’ She swept out of the room, the mouse and the ash forgotten, and Rose followed her, leaving Cinderella standing in the pile of grey dust. She was living up to her name at least, she thought as she got down on her knees once more and reached for the pan and brush.

I

vy and her Viscount arrived just after noon, in a glorious carriage driven by two perfectly matching grey ponies. Cinderella watched from the window as her step-mother ran out to greet them, loitering perhaps a little longer than necessary in the freezing weather, in order to make sure all the neighbours saw her daughter’s fine winter wolf stole and the rich blue of her dress. Cinderella thought she might kill for a dress like that, or even for a single ride in that beautiful carriage. Kill she might, but she wasn’t sure she would kiss the Viscount for any of it.