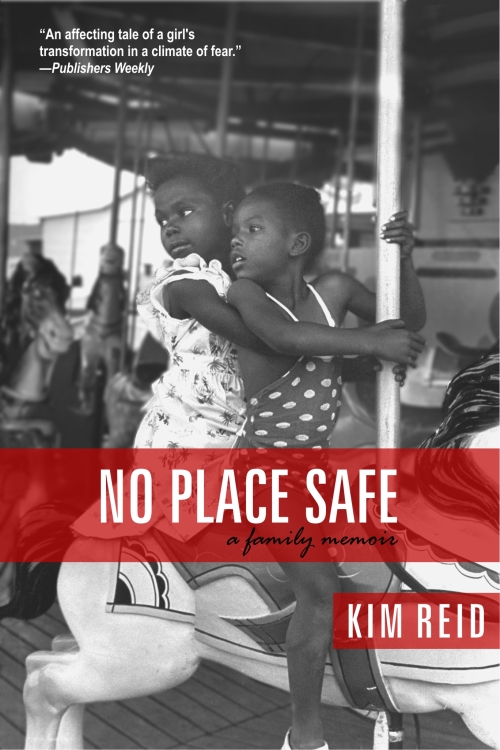

No Place Safe

Authors: Kim Reid

NO PLACE SAFE

A Family Memoir

Kim Reid

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

The summer before I started high school, two boys went missing and a few days later, turned up dead. They were found by a mother and son looking for aluminum cans alongside a quiet wooded road. It was already ninety degrees at noon, even with an overcast sky, because it was the end of July in Atlanta, Georgia, which I imagine is similar to the heat in hell, except with humidity. The mother thought she saw an animal at the bottom of a steep embankment that started its descent just a couple of feet from the road. The combination of heat and damp created a smell that frightened her. Something about the odor must have told her it wasn’t an animal at all, must have made her call her young child to her lest he discover the source. They left off the search for discarded cans and walked to a gas station where the mother called her husband, and he called the police.

The boys were friends; one was about to celebrate his fifteenth birthday, the other had just turned thirteen, the same age as I at the time. One went missing four days after the first, but they were both found on the same day, not two hundred feet apart in a ravine just off Niskey Lake Road. The two detectives first on the scene, responding to a signal 48 (person dead), noted in their report that either side of the road was bordered by trees, like most streets were in Atlanta at the time. Loblolly pine, white oaks, and the occasional stray dogwood that played unwitting hosts for the creeping kudzu vines that threatened to take them over completely. The officers also noted that the woods and ravines lining both sides of the road were “used as a dumping ground for trash.” This was where they found the first body. A vine growing from a nearby tree had already wrapped itself around the boy’s neck, unaware that his last breath had been stolen from him days ago.

While making notes of how the child’s body lay among other thrown-away items littering the road’s shoulder, the detectives caught an odor on a small, hot breeze coming from the north. They knew the smell immediately, and it led them to the second boy’s body. At the time, no one knew the boys were friends because the police didn’t know who they were. By the time school started, only one boy had been positively identified. More than a year would pass before a name could be given to his friend.

*

It wasn’t much more than a blip in the news—two black boys being killed in Atlanta in 1979 didn’t get much coverage. The only reason I knew what I did was because my mother, an investigator with the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office at the time, told me to be a little more careful. She said it was probably just a coincidence, but just as likely not, that the boys were close in age, black and found in the same wooded area.

Warning me to be a little more careful because those boys were killed was a waste of words. By my thirteenth summer, I’d learned to be nothing but careful, whether I wanted to or not. I couldn’t help but think like a cop. Even though they were my favorite, I rarely drank frozen Cokes because I avoided going into the convenience stores where they were sold (an off-duty cop still in uniform is a sitting duck if she walks in during a robbery). At restaurants, I never sat with my back to the door (you need to be aware of everyone who comes in and out, and know your entry and exit points). I always tried to carry myself like I wasn’t scared of shit (even if you are, don’t let them know or they have you). My friends called me Narc.

Ma told me about the boys while we got ready for work, sharing her bathroom mirror. I combed my hair while I studied her use of blush—the sucking in of cheeks to find the bones, the blowing of the brush to prevent over-application. This girly part of her never seemed to go with the other part, the other woman—the one who, as a uniformed officer, carried a .38-caliber service revolver in her thick leather holster, along with other things difficult to associate with a woman, especially a mother: handcuffs, nightstick, and the now illegal blackjack, solid metal covered in leather for handling an uncooperative perpetrator, or

bad guy

as I called them.

Perpetrator

filled my mouth in an uncomfortable way.

My use of cosmetics was limited to tinted lip gloss and a brush to tame my thick and unruly eyebrows. But I watched her anyway, filing away the technique for the time she’d let me use real makeup to turn my face into something that resembled hers.

“I’ll call a friend at the department to see what other information I can get on those two boys,” Ma said while she softened the tip of her eyeliner pencil over a match’s flame.

“Why?” I asked. “People are all the time turning up dead in Atlanta.”

“Something’s not right about it—them dying a few days apart, both being teenage boys and black, turning up in the same location. I’ll look into it, and in the meantime, you be watchful, and look out for your sister.”

Ma didn’t need to add the last part. When wasn’t I watchful? And I didn’t know any other way than to look out for my sister. Bridgette was only nine. I was the oldest, which meant looking out for her was my job.

I just told Ma, Okay, I’ll be careful. She was thinking there might be a pattern. She was always looking for a pattern in

everything.

The fact that the two boys were found so close together but in different stages of decomposition, a clue that they hadn’t been left there on the same day, made Ma think their killer was the same person and was using the wooded spot just off the road as a dumping area. I imagined a car slowing just long enough to open a door and toss out some mother’s child, like an emptied beer bottle or a tread-bare tire.

Beyond that bit of theory, Ma couldn’t come up with more.

Even if she was right about a connection between the victims, I didn’t see what I had in common with the dead boys other than being black and our ages being close. For one thing, they were boys, and everybody knew boys liked risk. Boys looked for trouble, and if none could be found, they’d make some up.

Ma said herself that most homicide victims were left not too far from where they lived or where they were killed. Niskey Lake Road was in southwest Atlanta, a good fourteen or fifteen miles from our house. Though they didn’t know it for sure, the cops were already speculating the boys were poor and messing around with drugs. There was nothing new in this theory—according to the police and the media, all black boys in inner-city Atlanta were poor and dealing. I didn’t know much about drugs other than the joint I’d sampled when I was twelve, during a summer vacation in Cleveland with my grandparents that freed me from Ma’s surveillance.

We did okay financially, considering we lived on a cop’s salary and there were no child support payments waiting in the mailbox, no sugar daddy to take up the slack. Neither of those income sources was my mother’s style. Maybe those boys were from the projects or nearby, and I lived in a house with a pool in the backyard. True, I lived within a couple of miles of two housing projects, but that was on the other side of Jonesboro Road—the side that led down Browns Mill Road to Cleveland Avenue and its pawn shops, check-cashing stores, and fast-food joints that filled our passing car with the smell of old grease. To me, it seemed a world away.

*

In between filling the dog’s water bowl and making sure Bridgette didn’t add more sugar to her Frosted Flakes, I began the morning countdown, telling Ma the time every three minutes to keep her on track because she was never on time for anything. You’d have thought she was an actress instead of a cop, as much time as she took in the morning. It probably would have made her cop life easier, but she didn’t pretend to be a man. She wore her hair long, although as a street cop, she’d had to wear it up. Long hair could get you into trouble when you’re trying to take down a bad guy. This is probably what made her popular with some of the more open-minded male cops, those who didn’t see anything wrong with a female cop as long as she was something to look at.

We rode together in the mornings because we both worked downtown, and I pestered her about the clock until the moment we were in the car. I hated being late for anything, much less a place where I was responsible for things. The source of my obsession with being on time is a mystery because Ma didn’t give me much of an example. Or maybe it’s because she didn’t. There were too many times when I was the last kid picked up from daycare, or school, or basketball games that she couldn’t get to early enough to watch me play. Put-out babysitters, teachers, and coaches would give me the evil eye in between checking the window for any sign of her, though when she finally arrived, they’d say, “Not a problem at all, I understand.”

Normally, I’d catch MARTA, the city bus system, to avoid having to depend on her. She let me start taking public transportation when I was eleven. After that, my tardiness could be blamed only on the bus driver, and even that rarely happened because I always tried to take a bus earlier than I needed to just to make sure I wasn’t late. But it was summertime and I was already getting up earlier than should be legal during summer break. Riding with Ma gave me an extra thirty minutes of sleep. When I’d finally get her out the door, I always thought we’d make it on time as long as we didn’t get stuck at the train tracks. More often than not, we did.

I left Ma in the parking lot in front of her building, the Fulton County Courthouse on Pryor Street, and walked the last half mile to work. Past the old entrance to Underground Atlanta, once a tiny city beneath the city (and now is again). Down Martin Luther King to Courtland and into the Georgia State University campus. And finally, over to Butler Street, where all kinds of things could be seen and heard: fights between spouses, patrol cars coming and going, people grieving, the homeless, people going about their every day, and ambulances screaming to be heard over all the rest.

My job wasn’t a paying one, but it should have been. I was a candy striper at Grady Hospital, which was like being a candy striper in a war zone. It seemed like a good idea when Ma said I needed something to keep me busy during the summer. I figured I’d get to wear a cute nurse’s outfit, and Ma always said I’d wanted to be a doctor since I was six, when she bought me a microscope for Christmas, complete with specimens pressed between small rectangles of glass. The job would give me a chance to find out whether this life of medicine was Ma’s dream or mine. True, I lied to the volunteer agency about my age, saying I was fourteen, but the job shouldn’t have been given to anyone under twenty-one, and even then, I’d have warned them to think twice.

The uniform was the first disappointment because there was nothing cute about it. Instead of being white and form-fitting as I’d imagined, it was a smock of blue-and-white-striped seersucker worn over a white blouse. The top half of the smock was apronlike, square-necked, sleeveless, and a size too small, pressing down my breasts like binding. The bottom half flared out, giving the impression my hips were far wider than they were. The candy striper uniform did nothing to help me broadcast my recently acquired curves. And the job wasn’t like what I remembered from the movies—handing out magazines, filling cups with ice chips.

Back then, Grady was the largest hospital in the Southeast. It was where people were sent when no other hospital wanted them—because they were on Medicaid, because they were shot while trying to kill the person who shot them, because they had no place else to go. It was where the ambulance took Ma after a car chase that ended badly. She said when you’re on the wrong side of the white light, Grady was the place to go if you weren’t ready to check out just yet. Once they saved you, though, it was another story. You had better get moved to another hospital quick.