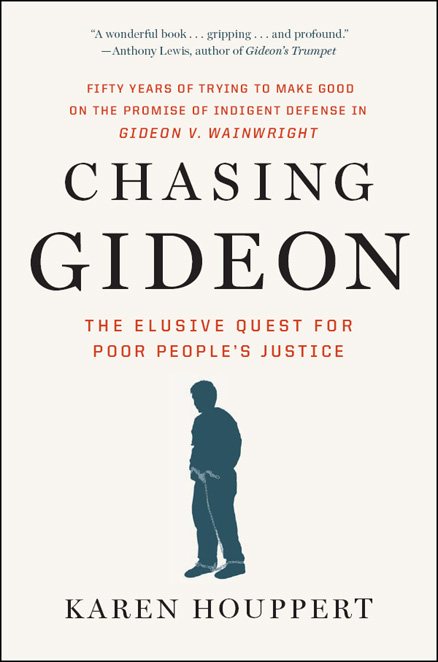

Chasing Gideon

Authors: Karen Houppert

CHASING GIDEON

CHASING GIDEON

The Elusive Quest

for

Poor People's Justice

KAREN HOUPPERT

NEW YORK

LONDON

© 2013 by Karen Houppert

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Earlier and shorter versions of the chapters “A Perfect Storm” and “Death in Georgia” were first published in

The Nation

.

“American Bar Association's Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System by the Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants” copyright © 2010 by the American Bar Association. Reprinted with permission. This information or any or portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2013

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Houppert, Karen, 1962-

Chasing Gideon : the elusive quest for poor people's justice / Karen

Houppert.

pages cm

“Earlier and shorter versions of the chapters “A Perfect Storm” and “Death in Georgia” were first published in The Nation.”

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59558-892-0 (e-book) 1. Legal assistance to the poor--United States. 2. Right to counsel--United States. I. Title.

KF336.H68 2013

345.73'056--dc23

2012047464

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

Book design by Bookbright Media

Composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Adobe Caslon

2Â Â Â 4Â Â Â 6Â Â Â 8Â Â Â 10Â Â Â 9Â Â Â 7Â Â Â 5Â Â Â 3Â Â Â 1

For Zack Houppert-Nunns

Â

Â

Â

M

arch 2013 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision

Gideon v. Wainwright

, which established the constitutional right to free counsel for the poor. Most Americans have a glancing knowledge of this basic right from popular TV shows such as

Law and Order

or

CSI

. We recognize it from the arresting officer who announces as he snaps on the handcuffs, “You have a right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.”

A half century has passed since the Supreme Court ruled in the

Gideon

case and since

New York Times

reporter Anthony Lewis penned his award-winning book recounting Clarence Earl Gideon's request for a lawyer to help him fight his burglary charge. Lewis's book,

Gideon's Trumpet

, was hopeful and optimistic about a future where effective legal assistance is provided for all criminal defendants, regardless of their ability to afford it. But a look at the state of indigent defense today reveals instead a situation in which citizens are routinely being denied their basic constitutional rights.

Enormous changes have taken place in the U.S. criminal justice system since the Supreme Court ruled in the

Gideon

case, including an explosion in the number of prosecutions, and in particular drug arrests, which swelled from fewer than 50 per 100,000 people in 1963 to 750 per 100,000 people by 2000.

1

The advent of mandatory minimum sentences and other harsher approaches to law enforcement,

applied broadly through the so-called War on Drugs, have raised the stakes and changed the dynamics of criminal defense. Plea bargaining, which now resolves more than 90 percent of all cases, positions the lawyer in particular constraints, as does the overwhelming caseload that so many criminal defense lawyers carry.

2

This book focuses on the stories of four defendants in four statesâWashington, Florida, Louisiana, and Georgiaâthat are emblematic of contemporary problems with providing lawyers to poor people throughout the country. In Washington, where teenager Sean Replogle hit another car and the driver later died, crushing caseloads in the public defender's office regularly compromise the quality of representation that poor and working-class defendants receiveâwith devastating consequences for the accused. In Florida, where Clarence Earl Gideon brought his original case and where Miami-Dade County's chief public defender for thirty-two years, Bennett Brummer, appealed to the courts themselves for relief from accepting more clients and providing inadequate representation a new chapter in the Gideon case unfolds. In Louisiana, Gregory Bright served twenty-seven years for a crime he didn't commit and Clarence Jones has sat in jail for more than sixteen months on a burglary charge, waiting for a lawyer to be appointed to him; here, the interplay of race, poverty, cronyism, high incarceration rates, and antiquated funding mechanisms create a dysfunctional indigent defense system in which innocent people are routinely jailed and denied basic access to an attorney. And in Georgia, where a jury sentenced Rodney Young to death in 2012 as valiant but underfunded defenders explained his mental retardation, disparate funding levels for prosecutors and public defenders can tip the balance between life and death.

Taken together, these four stories point to fundamental flaws in the way we provide legal representation to the poor in America. They also hint at solutions for reform, and this book documents some creative efforts to fix a broken system, as well as telling the stories of committed lawyers steadily working to deliver on the promise of

Gideon

.

These cases raise questions about how we as a nation will choose to define “justice.” By justice, do we mean that we will pay lip service

to the notion that everyone has a lawyer to represent them in court? That we will provide a warm body in a suit and tie to stand next to a defendant? Or do we mean to equate justice with fairnessâand actually provide folks who are accused of crimes with meaningful representation? Are we, in fact, committed to a level playing field, the adversarial system of justice in which both sides are properly armed to argue and from which truth emerges? Are we committed to making the system work as it is designed to? Back in the 1800s, Mark Twain joked that “the law is a system that protects everybody who can afford a good lawyer.” In many ways, that remains true.

HAPTER

1

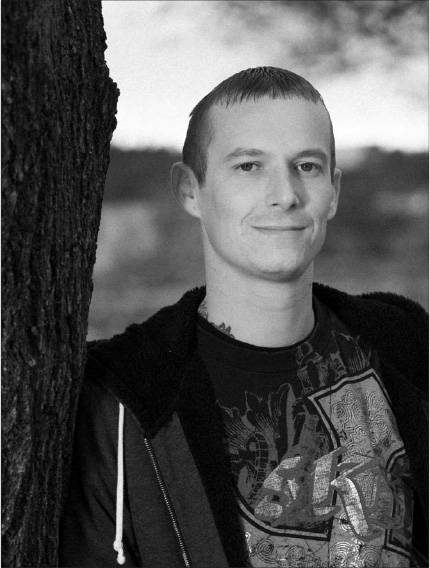

Sean Replogle in 2012. He is now twenty-nine, works in a fast-food restaurant, and recently served the cop who testified against him: “You tried to put me in prison at eighteen and sat next to me for eight days of a trial and you don't even recognize me?” Photo by Barbara Smith.

A C

ASE OF

V

EHICULAR

H

OMICIDE

Â

S

ean Replogle was a blond, rail-thin senior in high school when he turned eighteen on September 16, 2001. He describes himself as a “happy-go-lucky kid” with a lot of friends. Aside from catching it for occasionally skipping, he had never been in trouble at school. He'd certainly never been in trouble with the law. Indeed, it had been his wish since childhood to work in law enforcement; he hoped to be a cop someday. For now, though, he was flipping burgers at McDonald's after school. He worked hard and saved his wages. A few weeks after his eighteenth birthday, he used the $1,700 he had accumulated to buy a thirteen-year-old red Mustang.

His dad, Chuck Replogle, was proud of the fact that Sean had earned the money for his own car. And, in any case, he could not have helped. Chuck Replogle was a widower barely scraping by financially. He taught in a before- and after-school program at a local public elementary school. By working an early morning shift at the school, doing some carpentry in the afternoons, and then returning for a second shift at the school in the afternoons, he had been able to support Sean and his younger sister. Years ago, he made better money as a journeyman carpenter. But his wife took ill when Sean was very young. Disease sucked the life out of her; the hospitals sucked the savings out of the family's bank account. She died when Sean was a preschooler. Then Chuck was injured on the job and

had to find new, less physically demanding work. He loved his work with children, but his meager salary certainly precluded buying a car for his teenage son.

He couldn't even afford to help Sean cover insurance costs for the car. In fact, when Chuck took his son to the insurance office shortly after Sean bought the car and the agent changed the quote he'd given over the phoneâupping the amount by $40 due to Chuck's credit ratingâthey were stuck.

1

Sean was paying for the insurance from his McDonald's earnings and he didn't have the extra money either. He would get his paycheck the next day, Sean told the agent, and come back to settle things.

That, anyway, was the plan.

McDonald's paid Sean on Friday. On Saturday, the boy drove his new Mustang with a friend to the Moneytree to cash their respective checks. On the way home, Sean traveled the same route he had taken to his house hundreds of times before, driving his father's car. He turned onto Garland, a two-way street that ran ruler straight through a mixed-use neighborhood. It cut past a post office, past a slew of squat, sixties-era single-story ranches with flat green patches of lawn and cement drives, past the campers and faux-barn sheds and misshapen shrubs that distinguished the otherwise identical homes, past the Garland Avenue Alliance Church, past the low-slung brick Spokane Guild School & Neuromuscular Center. As Sean approached a cross street, he noticed a Toyota inching out beyond the stop sign to make a left turn. Sean had the right of way and, he says, assumed that the car would see him and brake. It did not.