Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

Chernobyl Strawberries (22 page)

In the summer of 1984, the Orwell year, I spent a month studying Bulgarian at the Karl Marx Institute of the University of Sofia. I rarely travelled eastwards in those days, where all there was to see seemed to be more of the same thing. I was doing some research on Byzantine prayers for my final dissertation at Belgrade University, and signing up for a Bulgarian language course, all expenses paid by the communist government of Bulgaria, was a way of getting me into the rich manuscript collections and archives of Sofia. I knew that communist propaganda would be offered in large dollops, and I didn't mind hearing some to earn my keep. I was in no danger of being reconverted.

Sofia was like the Belgrade of my early childhood, a smaller, cosier town, with fewer cars and fewer and emptier shops. Although I was there for the first time, nothing appeared to be really new. To the native speaker of Serbian, the language and the alphabet hid no secrets. The features and the physiques of Bulgarians were barely different from those of Yugoslavs, and even the food was the same. I felt almost at home, but for that noticeable difference in atmosphere which I associated with being behind the Iron Curtain, in the Eastern

Bloc proper. The volume was turned down by a few notches and the lights dimmed.

My schedules were full. We had meal coupons which we were supposed to exchange in particular student canteens, and concerts, folk dances and theatre performances we were supposed to attend almost every evening. We were clearly not supposed to wander too far off the programme. Still, I did not really mind this. I'd steal a few hours in churches and museums, and after about a week I had a feeling that I'd known Sofia all my life. The feeling was compounded by the way that I seemed to keep running into people who knew me. I once popped into a post office at the other end of town, only to be stopped by a stocky young man who asked me if I'd lost my way. For some reason, he knew exactly who I was and where I was studying.

I loved the sombre Soviet atmosphere of the Karl Marx Institute. Our orderly mornings were split evenly between language lessons and history lectures explaining the glories of Bulgaria. There was a lot in those lectures that might have been challenged. The Serbs shared a great deal of history with the Bulgarians, and âshared' was, more often than not, a euphemism for a complicated and sometimes fractious tangle. I was aware of different points of view but I never queried anything. It didn't seem courteous to my hosts, and they were nothing if not hospitable.

My month in Bulgaria was marked by some gloriously incongruous moments. There was, for example, a foreigners' disco at the students' hall of residence, which was obviously

the

place to see and be seen in Sofia. Every evening, it reverberated with the latest Western hits and young things turned and twisted under a complicated light show. Then there were cocktail parties and

receptions for young foreign scholars, with a seemingly endless series of toasts to international friendship proposed by illustrious Bulgarian academics.

One of these cocktail parties ended with a secret ballot in what was effectively a beauty contest. You participated simply by being present, and I came third, some ten votes behind a striking Kazakh girl called Leila and a tomboyish Australian blonde. I still remember Kazashka's exotic face, and her elegant, slim body, which looked glorious even in unflattering Soviet clothes. Somewhere among my papers in Belgrade I keep a diploma which congratulates me on being âMiss Bulgarian Summer School 1984: Second Runner Up', my trophy from the land behind the looking glass.

What âMiss Bulgarian Summer School...' doesn't quite know how to explain is the fact that that summer in Sofia she finally managed to lose her head. What a fantastic, dizzying feeling that was! It began the evening I arrived, while I was checking into my spartan room in the student hall of residence optimistically named Spring Quarters. Sitting just outside my room, there was this amazing young thing. His long body was sprawled across an armchair. He was wearing a blue cotton shirt in the most surreal print imaginable, a pair of green agricultural labourer's trousers and tennis shoes. Behind a pair of unusual gold-and-leather-rimmed glasses glinted a pair of green eyes. His hair was reddish-brown, and his skin hinted at a freckled childhood. His name was Simon.

He was obviously English, as English as the running tèam in

Chariots of Fire

, as English as Sebastian Flyte and the moustachioed First World War officers in my grandfather's albums of the Salonika campaign. Indeed, before long I found out that his grandfather had been just such an officer, fighting

the Bulgarians alongside my forebears. He was the kind of Englishman that I spent much of my English literature courses taking apart and yet had never met before. His Englishness was fascinating, but it wasn't quite what seduced me. Rather, it was the fact that he was both strange and different and yet entirely familiar at the same time, like a long-lost twin. Coming from opposite ends of the continent, we had somehow managed to acquire the same tastes in books, films and music, and we were drawn to the same kind of places. There was no need to be chameleon-like at all. I sensed that he could be dark and difficult and broody, but he made jokes which still make me laugh after twenty years.

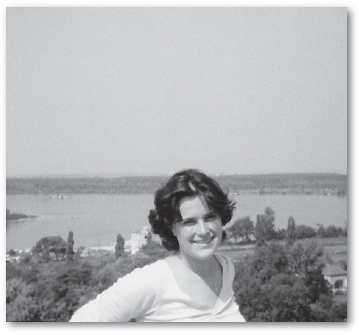

At the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers: an early photograph by Simon

If there was a difference between us, it was that I was intense and openly ambitious, while he affected incredulous ignorance as I went about giving mini-lectures on anything under the sun, particularly if it could be interpreted from a post-structuralist point of view. His amateurishness was a very English affectation, just as my earnestness was a very Central European one. We both earned our Firsts soon after that Bulgarian summer: I as though anything else was out of the question, Simon as though it was an afterthought.

Between Sofia and our wedding day, we had eighteen months of Bavarian rendezvous, simply because Bavaria happened to be approximately halfway between London and Belgrade. The names of Munich underground stations still echo in my head like the most erotic of poems. Allowing yourself to be seduced turned out to be much more exciting than seducing. For one thing, you never knew what was going to happen next. I was ready to follow the boy to the end of the world, to England itself if need be.

WHEN A MAJOR

misfortune overtakes us, people sometimes assume that â if it offers nothing else in return for the anguish â it might bring some kind of deeper spiritual insight. Suffering makes us better people â or so they say; it enables us to exhibit bravery; it makes us stronger; it brings us closer to God. We use such words of comfort because we have difficulty in accepting that suffering may come without any compensation and we create elaborate narratives of redemption around the pointlessness of pain. I can report nothing of this kind. I didn't learn anything, other than just how much pain I can take. While my cancer was attacked by poison, sword and fire, like a medieval beast, I didn't fear death. If one creates life, one doesn't just abandon the scene when the going gets tough. In a very unexpected way, the desire to be healed turned out to be about motherhood.

I continued to set the alarm clock for seven just in case I overslept, but I never did. I worked, I looked after my son and I kept the house clean. I prepared food even when the thought of eating made my stomach turn. I went from room to room with a red plastic bowl, always ready to throw up cleanly. I left handfuls of hair on the carpet, like a moulting dog. My skull emerged white and smoother than an ostrich egg. My little boy

caressed my bald crown and said, âMummy, you look like a hatchling.' I felt younger and more vulnerable than him.

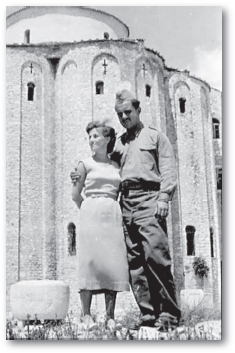

My mother visits my father on leave, 1959

When I should have been resting, I wasted time in bookshops as though there was no tomorrow, or, judging by the extraordinary quantities of books I kept buying, as if there was a superabundance of tomorrows. I wasn't really reading anything. I sniffed the fresh smell of print and caressed unbroken spines. I indulged in macabre calculations. If I had a year to live, then, at four books a month, there was enough time to read forty-eight books; five years â 240; fifty years â 2,400. That finally offered some consolation: even without

cancer, I could hardly expect to be alive fifty years from now, and yet 2,400 books seemed barely satisfactory. I already possessed 2,000 books I hadn't read, and was acquiring more each day. I was also devoting my hours to writing, which seemed a waste of precious time. I resolved to write less and read more. Reader, you are witness to my resolution.

After the first operation, I was told that I had clean, wide margins, like the books I enjoy most. I was given the odds on surviving five years, and they seemed very good, even though I couldn't really deal with odds. I am temperamentally inclined to believe that one in a thousand is somehow more likely to happen than nine out of ten.