Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

Chernobyl Strawberries (23 page)

God never spoke to me. It might be that my particular pain did not really stand out in the white noise emanating from the planet like steam from a boiling pot. I certainly wasn't unwilling to get in touch. I lingered in the semi-darkness of churches just before evensong, listening out for the thin, silvery rattle of incense burners. I said prayers in English, Serbian and sometimes even in Greek. (This last sounded most likely to get through, perhaps because I understood so little of it.) It felt a bit like praying for a favourable exam result when you'd already submitted the script: comforting but useless. It might simply be that I could never be sufficiently humble. Yellow-faced and radiation-sick, Baldilocks remained her obstinate self.

None the less, only bookshops and churches gave me the feeling that anything might happen. I didn't really believe in God as much as I believed in books, but I loved the sights and sounds of religion. The Byzantine chant of my ancestral Orthodoxy, curtains of incense and black-clad monks with beards untouched by razors, flocking like ravens on snow-covered forecourts; Anglican cathedrals in which stone seemed

as light as ice cream; the sublime, darkened beauty of London's Tractarian churches; the Baroque waxworks of ripe Catholicism â as far as I was concerned, they all provided a vision of humanity at its most endearingly hopeful. And London was the New Jerusalem: there was no religion in the world which didn't have a meeting house in one of its suburban terraces. Being ill in the British capital at the beginning of the twenty-first century was a bit like being a leper in the Holy Land in AD 33: there was never a shortage of volunteers to wash one's feet.

I went to synagogues and mosques. On balance, I preferred domes to arches: building a sphere, a woman's breast, seemed as close as both God and humanity ever came to perfection. Looking at the webs of unfamiliar script, I realized that the vocabulary of my own, non-existent faith was so bound up in the story of Jesus that I couldn't get him out of my mind. I said God and, pop, up came the long bearded face. Although I might have tried to undo such conditioning, it seemed hardly worth the effort. Since it was unlikely that I was ever going to believe, I might as well remain a Serbian Orthodox agnostic. Other religions appealed as stories, Christianity as a storybook with pictures.

If I believed anything, it was that â as the novelist Danilo Kis once said â reading many books could never be as dangerous as reading just one. My literary hoards offered a sense of peace that no single volume has ever been able to provide on its own, but I did begin to wonder what was behind my obsessive book buying. In my family history, building a library has always seemed a bad idea. Books vanished when your house was hit by a bomb or torched, and they were what had to be left behind when you moved abroad. In difficult times, a diamond ring could always be exchanged for a pot of goose fat in one of the villages surrounding Belgrade. All a book can do is burn.

I am a compulsive reader. Quality doesn't really come into this. On crowded underground trains, when there is no room to open a book, I will read safety warnings and advertisements, breaking the lines in different places to create a poem. Put me into a bare hotel room and I'll go through the phone directories imagining local lives, the way other people may flick through satellite TV channels. On those occasions when I said âyes' to proposals I'd never intended to accept and was then duty-bound to oblige, it happened because I was reading while pretending to listen. If I travelled anywhere, the safe bet is that I carried more books than clothes, fearing that I might run out of things to read. Even then, I went straight to the airport bookshop to buy more.

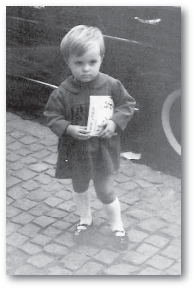

Two years old, with my favourite book

Feverishly starting a new volume, reading to page sixty or thereabouts, and then moving on to the next one, so that I always had at least six or seven books on the go, has always been my particular vice. Books gathered by my pillow, in my desk drawers, in bags abandoned at the bottom of my wardrobe, like sweet wrappers in a child's pocket. The space under my bed was known in my family as the Library of Congress. If I woke up in the middle of the night, I'd reach down there and pull out a book to continue to read from where I last left it, the place marked by a bus ticket from Tel Aviv to Acre dated 1988 or a letter I began writing seven years ago. My memories of places became inseparable from the books I first read while visiting them. Sometimes the connections made geographic sense â like discovering André Aciman's

Out of Egypt

in Alexandria â sometimes not at all. I read Kis's

Early Sorrows

while staying with a retired colonel in Peshawar, and the book still colours my recollections of the North-West Frontier Province with Central European melancholy.

My fondest memories from abroad are those of standing in bookshops, inhaling the familiar smell of leather, paper and fresh print. On one of my earliest visits to England, I discovered paradise in the shadows of St Paul's Cathedral. It was a bookshop where books could be had for free if you plausibly impersonated a visitor from behind the Iron Curtain. I am not sure which democracy-loving, communist-hating organization funded the enterprise. The little shop was well stocked with the works of dissident East European authors and right-wing economic theory. The former enthralled for hours. Every book ever banned in the East seemed to be there, from the grand-daddy of dissidents, my Montenegrin compatriot Milovan Djilas, to the Bulgarian Georgi Markov, who was murdered

with a stab from a poisoned umbrella tip on London's Waterloo Bridge. Elegant novels written by Czech rubbish collectors stood next to Albanian essayists, and imprisoned Romanian poets vied for shelf space with Lithuanian philosophers. When you chose your books, an elderly bookseller (or book-giver) produced a form which required your signature and address. For some unaccountable reason, I gave a Bulgarian name, feeling, perhaps, that the provenance was more suitable for a recipient of such literary gifts. It didn't seem like the sort of place where anyone would ask you to produce your documents: that would be too much like home. By the time I settled in London, my paradise had gone.

In my second year at Belgrade University I decided to become a palaeographer. I gave up work as a youth radio presenter in order to join a course in Byzantine Greek. My mother was distraught. My bright media future was evaporating before her eyes, giving way to musty old libraries and mustier salaries. Working with old manuscripts did not seem at all glamorous to her. She thought I was too good-looking to be a palaeographer. Granny was worried that I might catch bubonic plague from a bug dormant in some twelfth-century manuscript which I happened to open for the first time since its scribe collapsed, hands covered in horrible, pus-filled fistulas, clutching his quill pen. Only my father saw some consolation in the fact that it was the kind of work which was unlikely to lead to imprisonment. There seemed to be nothing remotely political in transcribing thousand-year-old prayers, whereas as a media star I was likely to shoot my mouth off sooner or later.

My medieval literature tutor, an erudite Byzantine scholar who was quietly anti-communist and unapologetically elitist in his ideas of higher education, took much of both the

credit and the blame for this sudden conversion. He guided me and Irena, a fellow literature student and one of my closest friends, to every manuscript collection in Belgrade, there to discover the secrets of book-copying. Irena was a gentle, blonde Montenegrin girl who reminded everyone of Mariel Hemingway in Woody Allen's film

Manhattan

, and our tutor â in his tweed jackets, turtle-neck jumpers and round spectacles â was most comfortingly donnish. Of the three, I was the one who was least like a palaeographer. I could never decide whether to dress like the businesswoman of the year, a lover of Jean-Paul Sartre or a punk.

The archives, with their old bookcases and desks, provided a refuge from an increasingly impoverished, polluted city. Belgrade was becoming like Cairo without the pyramids, or Erzerum with traffic jams and queues. The quiet world of faith inscribed in red initials and black continuous script seemed to provide the best sanctuary I could find. I might not be able to believe in God myself, but I was awed by the belief I witnessed. Irena and I looked at textual variants and transmission errors, we measured column widths, counted accents and breathings, and tabulated the family trees of manuscripts, feeling frighteningly, wonderfully grown up. I am not sure if any English undergraduate would be allowed to lay his or her hands on such treasures. Irena is still a gifted palaeographer. I obviously had no staying power. My mother was right: I was not cut out for archival work. I wanted to be quiet and at peace, but I was one of those children who are always, and in spite of their better judgement, driven to giggles by too much silence.

In fact, while it was highly unlikely that a palaeographer would end up in prison or without a job, as has been known to happen to the critics of contemporary literature, my father was

wrong in thinking that the vellum-bound world was apolitical. You could say, for example, that a manuscript was âprobably Bulgarian' or âpossibly twelfth-century', and cause an international dispute of major proportions. In the Balkans, there has always been an unspoken competition as to who was the first to be civilized as well as to who was the most civilized. Manuscripts provided forensic evidence. Given that medieval monks left relatively few clues pointing to their chosen national identity, one sometimes felt a bit like a Mormon, rechristening one's ancestors. Certainly, whether Methodius the Hypothetical was a Bulgarian, a Serb or quite possibly Greek seemed so much more important than whether T. S. Eliot was British or American. My on-the-one-hand-and-then-on-the-other attitude was never going to be an asset. As a palaeographer, you were expected to have an opinion, and I've never had an unqualified opinion in my life, at least not until I was forty-one.