Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul (28 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

After his wan proclamation, came silence. There were no comments about how beautiful the baby was, no questions about what his name would be.

Even the baby was silent.

I dared not ask what was wrong, though I knew there was something. Doctors and nurses huddled at the end of the delivery room. They worked with frightful efficiency, brandishing a menagerie of medical equipment to prod my baby to breathe. Within minutes they whisked Ethan to intensive care. Soon, the physicians rendered the diagnoses—meningitis, pneumonia—massive, life-threatening infection.

My husband and I began what would become a routine— visiting the intensive-care unit to spend time with our son. As we sat at his bedside, we couldn’t help noting that he wasn’t the baby we’d imagined. His tiny arms were restrained and his head shaved to accommodate piercing intravenous needles. Swaddled in a latticework of tubes and needles, his breathing was performed by the whoosh of a ventilator. More machines beeped and hummed an odd lullaby.

Because of the equipment, we couldn’t hold Ethan. Because he was sedated, we couldn’t even look into his eyes. Still we went, and the first tenuous days melted into weeks. Ethan was our son, and we couldn’t have loved him more if he’d been the rosy Gerber baby of our dreams.

Despite our love, the neonatal intensive care unit was a grim place. We parents wandered the corridors, yet we rarely spoke to each other. Dark circles ringed our eyes, and our faces had “Why me?” expressions. Instead of talking with each other, we spoke to doctors, steeling ourselves for depressing conversations where words like

brain damage

and

seizures

were used with alarming indifference.

To escape, I cried and ate big bags of M&M’s. And I prayed like I never had before, my faith bolstered by my need for a miracle. Mostly I waited and hoped for my baby to get better, while the days faded into each other.

One day, however, was different. I started my hospital visit like all the others, by scrubbing my hands with pink disinfectant soap. As I dried them, I noticed they were raw and bleeding from frequent washing with harsh antiseptic. Next I grabbed a sterilized cotton gown and pulled it over my head. The gown felt scratchy and the sleeves were too tight over my winter sweater. Even the color annoyed me—the sunny yellow seemed too cheery for mothers of sick and dying babies. I would have been more comfortable in drab gray or murky blue.

I trudged down the familiar hallway, barely noticing the piquant smell, a mix of alcohol and baby powder. I looked away from murals of smiling bunnies that seemed out of place in this somber setting. I walked by rows of isolettes and their small occupants, premature infants wrapped in cellophane to keep them warm, newborns with birth defects, and older babies who would never have a home outside the hospital.

At the nursery door, I braced myself to see Ethan and hear the day’s report of his condition. I knew it wouldn’t be promising. At two weeks, Ethan was still on the ventilator, still racked with seizures, still poisoned by menacing bacteria.

Then I heard it. A sound I hadn’t heard since the day Ethan was born.

Laughter.

It was not the polite, tinny laughter of visitors who were trying to relieve tension, but real laughter. Boisterous, robust and loud. It was coming from Ethan’s nursery. The sound was so alien, I wasn’t sure whether I welcomed it or felt threatened by it. Why would anybody laugh here, of all places?

I peeked inside the door to see a group of parents and nurses standing at one end of the nursery, gathered around a nurse named Gloria.

“Good morning!” Gloria called as I walked in the door. “It’s great to see you. How are you doing today?”

“I’m okay,” I said in a bland voice, still mystified by the cheery atmosphere.

Gloria grinned and waved me inside as she continued her one-woman show. I knew Gloria; she had taken care of Ethan. She had struck me as competent, sensitive and happy. But, tonight she looked positively radiant, as she regaled the listeners with funny stories of hospital life.

I wondered, at first, whether the babies were safe, since all the nurses appeared to be playing hooky. But I knew the nurses would notice the most subtle beep or buzzer while they had one eye on Gloria and one on their small charges. I joined the group and listened to Gloria’s impromptu performance. Though I can’t remember any of the stories she told, I remember how I felt while listening to her. At first, I smiled. Then, slowly, I dared to chuckle. Before long, I was laughing along with the crowd.

Initially, a pang of guilt pierced my heart. How could I laugh, when Ethan was fighting to live? But as I watched Gloria, these feelings dissipated. Her broad shoulders heaved and her frizzy, dark curls bounced as she entertained us. Her black eyes sparkled, and her lips turned up in an engaging smile. It was impossible not to be enchanted by her joyous spirit.

The more I laughed, the lighter I felt. My depression lifted, freeing my spirit from suffocating sadness. I welcomed the sliver of light, the brightness of hope. Nothing had changed with Ethan, yet I knew that whatever happened, I could handle it.

Gloria’s one-woman laugh-fest marked a turning point in Ethan’s hospitalization. After that night, I sought out Gloria whenever I visited the hospital. If there was bad news, I wanted to hear it from her. When test results came back from the lab, I wanted Gloria to decipher the numbers for me. When the time came to hold Ethan, to feed him and care for him, I wanted help from Gloria.

Gloria did help, with those tasks and more. She helped Ethan fight off the microscopic intruders that ravaged his body and the miracle I prayed for became a reality. But Gloria helped heal me as much as Ethan. Through the healing power of humor, Gloria gave me the will to smile and the courage to hope.

Lisa Ray Turner

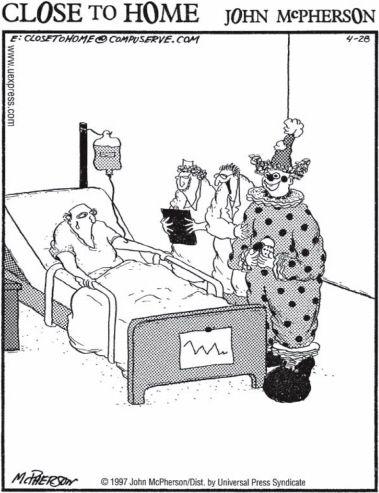

“We’re conducting a study on the healing power of humor. As Boppy performs for you, let us know the precise moment that you feel the kidney stone pass.”

CLOSE TO HOME © John McPherson.

Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL

PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

O

f all the joys that lighten suffering Earth,

what joy is welcomed like a newborn child?

Caroline Norton

I was the nurse caring for the couple’s newborn first child after his cesarean birth. Since the mother was asleep under general anesthesia, the pediatrician and I took our tiny charge directly to the newborn nursery where we introduced the minutes-old baby to his daddy. While cuddling his son for the first time, he immediately noticed the baby’s ears conspicuously standing out from his head. He expressed his concern that some kids might taunt his child, calling him names like “Dumbo” after the fictional elephant with unusually large ears. The pediatrician examined the baby and reassured the new dad that his son was healthy—the ears presented only a minor cosmetic problem, which could be easily corrected during early childhood.

The father was finally optimistic about his child, but was still worried about his wife’s reaction to those large protruding ears.

“She doesn’t take things as easily as I do,” he worried.

By this time, the new mother was settled in the recovery room and ready to meet her new baby. I went along with the dad to lend some support in case this inexperienced mother became upset about her baby’s large ears. The infant was swaddled in a receiving blanket with the head covered for the short trip through the chilly air-conditioned corridor. I placed the tiny bundle in his mother’s arms and eased the blanket back so that she could gaze upon her child for the first time.

She took one look at her baby’s face and looked to her husband and gasped, “Oh, Honey! Look! He has your ears!”

Laura Vickery Hart

F

or health and constant joy in life, give me a

keen and ever-present sense of humor; it is the

next best thing to an abiding faith in providence.

G. B. Cheever

When I was a teenager I worked at a nursing home as a nursing assistant. Although the hours were long and the duties not always pleasant, I developed an understanding, respect and love for the residents. Elmer, a patient with Alzheimer’s, was a favorite of mine.

Elmer was transferred from a facility cited by the state for inadequate care. He had no relatives to watch out for him— no one to care. Faded blue eyes, glistening with the dewdrops of old age, stared vacantly past the world around him. Inadequate care had left him bent at the hips and bent at the knees. Like a child’s zigzag line of indelible ink on the wall, the damage could not be erased. His wasted legs belied the muscles that once strained in the fields in the hot summer sun. Although his arms remained as strong as the mules he once drove, he could not conceive the limitations of his legs. We were forced to keep him in restraints.

But Elmer’s mind, unencumbered by the confines of reality, remained free to enjoy the pleasures of his past. Elmer still smelled the sweet of the evening dew on the new-mown clover. He still wiped the sweat from his favorite horse as they ploughed the frosty ground in the early spring. But Elmer no longer combed the fields and swamps looking for his cows. That chore was mine.

The first evening as I readied Elmer for the night, he asked, “Did ya bring the cows home?”

“Yes,” I replied, “I brought the cows home, Elmer.”

“How many?”

“Ten.”

“Well, ya missed three. Best go back and find them before nightfall. They won’t be safe out there.”

The next night Elmer again asked about the cows. “Bring the cows home?”

“Yes, Sir, I did.”

“How many?”

“Thirteen.”

“Gosh darn girl, ya missed two. Go back to the swamp and get the others. They won’t be safe out there.”

And so it went, night after night. I was rarely able to predict the number of cows that would bring the desired response—“good girl.” Sometimes I was sent to the neighbors to return a few cows because they “surely aren’t ours.” Sometimes I was told to wait out the storm before I went looking for a lost calf. Same time, same place, same station—but

never

same number of cows.

One night I arrived to find Elmer’s bed empty and unmade—not a good sign in a nursing home. I cried out, “Elmer.” No response. I ran to the nurse’s station and asked if Elmer had died. He hadn’t.

“Has he been moved?”

“No, he hasn’t.”

“He’s not there,” I worried out loud.

“He has to be. He can’t go anywhere; he’s tied in.”

Running back to his room, the nurse and I called, “Elmer!

Elmer!

” Searching his room, I noticed his restraints were tied below the bed rails rather than through them. The crossed part, the part that should have been under the bed, was on top. I knelt on the floor and looked under the bed. There, suspended in his restraints, hung Elmer.

“Get the cows home?” he asked patiently.

Susan Townsend

T

he crisis of today is the joke of tomorrow.

H. G. Wells