Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers (2 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Teachers Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Every time I speak, I realize that it is because of her kindness and encouragement. In the loneliest part of my childhood, she taught me to speak the language and understand life in America.

For a number of years, my father tried to get our family out of Poland.

The government did not allow us to leave. Warsaw would give us a passport but then not our visa. Once the passport expired, we would be granted a visa.

You can imagine my father's frustration.

One day, a Polish Communist official was expelled from France. This man was a friend of my father. So my dad asked him to intervene on our behalf in Warsaw. Our papers almost miraculously appeared.

I said good-bye to my teacher and schoolmates. Fearing some unknown reversal of fortune, we took only what we could carry and quickly departed for the United States.

I met Holly when my parents put me into St. Stanislaus Catholic School in Youngstown, Ohio. This was a Polish parish. Almost all the nuns who taught at St. Stan's spoke Polish. My parents knew that a language barrier would cause me difficulty in an American public school.

Even though in 1964 I was almost eight, the nuns decided that I should begin in first grade. They knew of a little girl in the first grade who possibly could help me.

My desk was put into the back of the classroom, right next to Holly's. When the teacher spoke, Holly occasionally would lean over to me, brush her shoulder-length, dark-mahogany hair away from her face, hang it over her right ear and whisper to me a Polish translation of what the teacher had just said.

At first, I spent most of my time staring as I looked around the classroom. In my school in Poland, there was no statue of a man nailed to a cross hanging over the blackboard.

In my classroom in Poland, we did not have one single picture on the walls. Nor had I ever seen a picture of a black-bearded man with a tall hat or a silver-haired old man who appeared to be trying hard not to smile.

Holly told me that they were among America's former presidents and that they were being honored that month.

Holly seemed to enjoy helping me. Her birthday party was the only one I was invited to that year. She even took time from her friends Grace and Cheryl and played with me at recess.

She was my translator on the playground. However, when kids called me a “dumb Polack,” she would explain to me that they were not being nice. To this day, I still don't understand why some of them called me “Herman the German.” Maybe it was because I was European.

Even though a nun taught our class, Holly was my true teacher. By teaching me English, she allowed me to become involved in class.

I soon forgot about my cherished ice skates, which I had left behind in Poland. I stopped crying at night for my Polish friends, grandparents, aunts and uncles. Holly made me look forward to going to my new American school.

By the end of the school year, because of Holly, I was starting to understand English. And the little girl who had given me the gift of language had also become my friend.

That summer, we moved only a block away from Holly's house. She and I played together as often as possible.

To Holly Warchol, wherever life has taken her, I would like to whisper

dzekuje

â“thank you” in Polishâinto her ear.

Stan K. Sujka

Stan K. Sujka

I

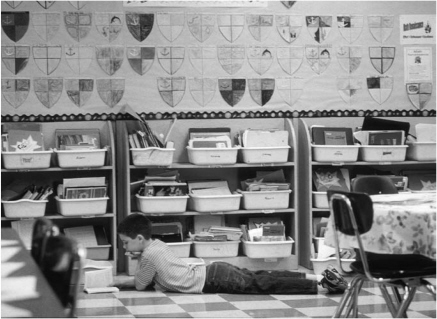

joyously anticipate the second semester of first grade. The children have matured by then, and many are good readers. Because they are capable of writing simple and sometimes even complex sentences, I introduce them to journal writing. I am propelled by the students' excitement as they each receive a brightly colored spiral notebook. They eagerly date their entry each day. I give them topics or story starters to start them offâ for instance, “I Get Scared When . . .” or “My Favorite Animal.” For many, creating an illustration with their entry is a favorite part of journal keeping and is particularly important to the child who is struggling with writing skills. Quite often, too, we have a “free” writing day when they initiate all their own ideas.

Although writing in a journal is primarily a personal endeavor, the children often ask to read their writing aloud to their classmates or to me. I am gratified as a teacher when they stand close to me andâquietly but excitedlyâread what they have just written. There is magic in their effort to phonetically write and then read words freely without correction or criticism. They smile and giggle as they read their own words. Describing everything from slightly exaggerated camping trips to painful feelings of hurt and sadness, I marvel that at such a young age they are able to express themselves with great depth and creativity. The interest the children show in each others' journal entries is amazing, too.

They listen and laugh spontaneously as their classmates share funny experiences about learning to swim or ride a bike. They identify easily with getting embarrassed at a friend's birthday party when they get cake frosting all over their mouth and nose.

It wasn't, however, until one spring Open House that I truly saw the power of journal writing. The journals, like other projects, were laid out on the desks. Most parents opened the journal, turned a few pages and glanced at the words. But that day, I noticed one little boy who went to his desk and sat down. His mother knelt beside him and listened as he read. Then she put her arm around him and spoke softly. I heard her say, “I didn't remember that! Really?” He nodded, and they both laughed.

Here was the value of writing and the importance of self-expression. The child, through his own words, was conveying who he was. He was grown up and powerful. For an instant, his writing allowed his mother to see inside him. She grasped the journal in her hands, pressed it to her chest and said, “I'll treasure this.” The little boy looked into his mother's eyes, quickly put his head down and grinned.

Julia Graff

Julia Graff

S

econd-grade math can be challenging, and not just for the students. As a second-grade teacher I was always looking for new ways to help my students understand the concepts of “borrowing” and “carrying” when doing addition and subtraction problems.

Lynn was having a particularly hard time with subtraction. Every attempt to help her understand was met with the same blank look. Her difficulty focusing on a task was not helping matters.

Determined to help her be successful, I worked with Lynn, one-on-one, every day for a few minutes during recess. We tried large-muscle activities, manipulatives and worksheets. Sometimes we would sit together at her desk and work. She enjoyed the extra attention, but still the concept eluded her.

One day, it seemed as if the light was finally beginning to dawn for Lynn and subtraction. We were standing at the chalkboard working on a subtraction problem. Her normally distracted demeanor was subdued, and she was intently watching me, hanging on my every word.

Silently I was congratulating myself and reveling in one of those rewarding moments in teaching when you know that learning is taking place.

When I finished my explanation, I was confident that we had had a breakthrough. Lynn's attention had not wavered.

“Do you think you understand it now, Lynn?” I asked, sure that I was destined for the Teachers Hall of Fame.

Lynn paused, still focused on me. With furrowed brow, she cocked her head to one side. Pointing her finger up toward me, she finally spoke. “Mrs. Henderson,” she asked, “are those your real teeth?”

Sara Henderson

Sara Henderson