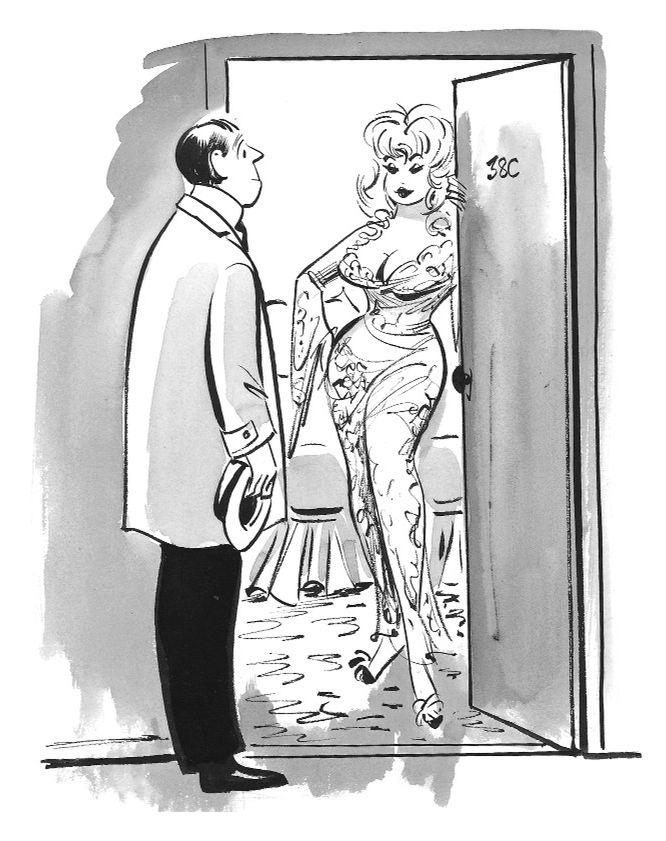

Coffee, Tea or Me? (27 page)

Read Coffee, Tea or Me? Online

Authors: Trudy Baker,Rachel Jones,Donald Bain,Bill Wenzel

“I feel great rapport with you, Trudy,” Scranton said, “and I’d like to help you. Like a father. I want to keep you from falling into the pitfalls my daughter has suffered.” Then he tried to kiss me and pinched my rear end.

“You’re no father.”

“I am. I am. Let me tell you . . .”

It was news time on the radio. To the accompaniment of staccato telegraph keys, whistlers, sirens, drums, and wind machines, all the world’s gruesome headlines were given with breathless excitement.

“We’ll be back in a moment with the details.”

Then a message from a clothing store with “Jingle Bells” playing in the background.

“Let me have the key to the room, Trudy.” Rhonda stood with her hand out. I gave her the key. She left with the captain. Charlie Smagg laid down on the bed and curled up with the pillow. “This news makes me sad,” he said. He switched stations. There was Christmas music everywhere. He settled on the original station. He hummed along with “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.”

“Actually, Sonny Tufts and King Kong are the kings of trivia. Did you know that?” Josh Pierre was still holding court, although one of the girls had left his circle and joined Charlie on the bed.

Every party emits its own particular sense of things to come. You could perceive upon entering Charlie’s room a distinct emanation of future wildness. That’s fine, in many cases. But the people in Charlie’s room weren’t right for some unexplainable reason. Scranton Rigby and his paternal line, the waltzing heavy-equipment salesman, little Josh Pierre, the other girls, and our own crew didn’t seem to mesh. Maybe it was just the time and the place. At any rate, the end result was depressing. The room was terribly hot, the music too loud, and the overt advances of the fellows a little too overt. I wanted to get out of there. “Do you want to throw snowballs?” I asked Rachel.

“Hey, gang,” Rachel announced. “I’ve got a great idea. How about a snowball fight?”

The suggestion was met with mixed reactions. But the lack of unanimity didn’t deter us. Rachel flung open the door, the blast of cold, wet air causing her to catch her breath.

“Come on,” I yelled, “let’s go.”

No one moved except Rachel and me.

Rachel put on her coat and ran outside. Soon, a large, wet snowball came flying through the door and splattered with a dull

sqump

against Josh Pierre’s lapel.

sqump

against Josh Pierre’s lapel.

“Let’s get ’em,” Charlie yelped and raced outside. Others followed. Only Josh remained in the room, a sophisticated sneer on his face showing his contempt for such sophomoric conduct.

The snowball fight was fun until the heavy-equipment salesman pinned me down in the snow and used the spirit of the fight as an excuse to slip his hand under my coat. I let him have it in the face with a solidly packed snowball and slipped out from under him as he sputtered the glaze off his face. Two of the stewardesses were sitting on top of Charlie Smagg and shoving snow down his shirt.

Scranton Rigby, tottering unsteadily on a small snowbank, threw a snowball at me as I ducked behind a bush by the motel’s entrance. He missed me, of course, but made a direct hit on the desk clerk who’d ventured out to watch the fight. That brought him into the fray with a great deal of zeal. He tackled Rachel and her screams indicated more than a simple snow fight. Scranton Rigby, father image that he was, jumped on the desk clerk. The clerk got up, swore at everybody, and went back into the motel. It was only fifteen minutes before the police arrived.

They were nice about asking us to stop the fight and return to our rooms. We all went back to the party room and sat quietly as melting snow formed little puddles on the brown tweed carpet.

Cooled off by the snow and the local policemen, the party resumed with noticeably less gaiety than before the outdoor frolic. Drinking was moderate, chatter was relatively subdued, and dancing was formal to the point of stiffness. Charlie Smagg was sober. Josh Pierre was falling asleep in the chair. The heavy-equipment salesman told jokes and Scranton Rigby laughed at them.

The party started to break up at about 2 A.M. The local radio station was still filling the airwaves with Christmas music, the late hour cutting down on the frequency of commercial messages.

“Wake up, Mr. Pierre,” I said, gently shaking the little fellow’s shoulders.

“Momma, Momma,” he babbled as he came out of his sleepy slump in the chair. “Oh, here I am. Right. Thanks.”

Charlie Smagg was asleep on the bed, the bottle still clutched tightly in his arms. Scranton Rigby reminded me to keep in touch with him.

“If you’re ever in Pittsburgh, drop in,” were the heavy-equipment salesman’s parting words.

“We sure will,” we answered him.

We were outside before we thought about Rhonda and the captain.

“There isn’t anything we can do,” I told Rachel as we shivered against the wind. “We’ll just knock and tell them we’re tired and want to go to bed.”

We did that. We were frozen by the time they came to unlock the door. The captain was dressed but Rhonda was in her robe.

“See you tomorrow, girls,” he said as he returned to Charlie Smagg’s room. Rhonda turned down the covers and climbed into bed. “Good night,” was said all around and sleep came quickly.

The telephone’s harsh jangle brought us out of the first hour of sleep. It was the captain.

“Sorry to bother you but I thought you ought to know we dumped one.”

It took a minute for his terminology to be understood, but I finally realized he meant our airline had lost an airplane.

“Where?”

“Over Wisconsin. It was on the news just now. Not much detail.”

“Any crew names?”

“Not yet. No sense losing sleep over it. We can’t do anything. We’ll find out all about it in the morning. Say good night to Rhonda for me.”

“Sure.”

Our captain, a twenty-year veteran, could go to sleep; he’d been around before when planes went down. But we hadn’t. We turned the radio on and waited impatiently for the next newscast. Then the announcer broke in on the music with a bulletin.

“The plane was believed to be carrying a full load of holiday passengers, but the exact number is not known at this time. Officials of the airline have indicated no known cause for the disaster. Stay tuned to this station for further details.”

We tried to stay awake but couldn’t. We woke up in the morning to a newcast in which they listed the names of the crew members. We didn’t know any of them, except one.

“. . . and Miss Sally Lu Johnson.”

“You know,” Rachel said slowly, “if I had to pick someone from our class at school who would end up like this, I think I’d have picked Sally Lu.”

“She was going to quit when Warren bought his own gas station. Looks like he didn’t make it quick enough.”

I started to cry and so did Rachel. Rhonda didn’t know Sally Lu, but she wept, too.

I guess all stewardesses have a true feeling toward the other girls, whether they’re close friends or not. We work together in such narrow quarters. We share our after-work lives with each other. We depend on each other. Folded away in the back of each of our heads is the knowledge that danger and death are always out there waiting. We know this. We accept it. I think each of us develops almost the same philosophy: if it’s meant to be you, it will happen to you. If it’s not your turn, you’re OK. And this is the way we would want to go—if it must be.

Rhonda tried to comfort us by telling about her own very bad experience. She’d had a big romance going in New Orleans and wanted to stay on for a few days. When she reported in sick, her roommate took over the flight for her. The plane went down in the Rockies. Her roommate’s body was never found. “My first thought was that I’d killed Gerry,” Rhonda told us. “I’d sent her to her death. I was torturing myself with guilt. I didn’t think I could fly anymore. But after a while I had to accept that this is the way it is. We all have a turn. Sally Lu just didn’t make it.”

Breakfast with the entire crew was filled with talk of the crash. Each one of us reported what we’d heard on the radio, and the cockpit boys went into their theories about what might have happened.

“Well, how do you feel girls? Ready to make the trip back?” The captain looked us straight in the eye with the question.

“I’m shook a little,” I answered him.

“Well, don’t be. Did you know that more people are killed at railroad crossings every year than in aircraft accidents?”

“And more people are killed on bicycles,” Charlie threw in.

The statistics weren’t at all comforting. “I don’t think Sally Lu knew about those statistics,” I answered

“Well, you’ll get over it. You have to.”

He was right, of course. And we did. We left the motel for our trip back to Kennedy. We finally got a break in the weather late that afternoon and were at our apartment building at seven that evening.

There was a telegram in the letterbox from Rachel’s mother. It read, “CRASH TERRIBLE THING. THINK YOU MUST STOP FLYING. PLEASE. LOVE MOTHER.”

“It’s funny, Trudy, but I don’t feel that way. I don’t think I’ve ever felt more like flying. Know what I mean?”

“Yes, I do.”

In front of our apartment door a happy surprise was waiting for us. Chuck was sitting bolt upright against the door, fast asleep. I fell into his arms. “You big goof,” I cried, “what are you doing here?”

“I was in Chicago with a forty-eight-hour layover when I heard about Sally Lu. I knew you were socked in up there in Rochester. It must be a helluva Christmas for you, so I dropped by and figured I’d wait for you.” He looked at his watch. “Come on, I’ve just got three hours. I’ll buy you Christmas dinner.”

Rachel suddenly started to remember an appointment with her friends in Great Neck. Chuck grabbed her arm and gave her a bright blue stare with those crazy eyes of his: “No party-pooping. It’s both of you pigeons for Christmas dinner, or nothing, OK?”

“OK,” Rachel said, retrieving her arm. “Do you have your bike outside?”

“This kind of weather I use reindeer,” he replied.

“Come on, kids, let’s go,” I said. We dropped our bags in the apartment and then, each of us clinging to one of his arms, we walked Chuck around the corner to a little French restaurant. I don’t know whether Chuck was in exceptionally great spirits or whether he thought he ought to be to cheer us up. Anyway, he kept us laughing during the entire meal.

“I’ll never get over the things you girls do to each other,” he told us at one point. “Remember your chesty friend Betty?”

“Sure, we see her all the time.”

“Well, she was hot after the captain on a flight I was on to Phoenix a couple of weeks ago. The junior stew was a young kid just out of school—a fresh, on-the-make little doll. We all noticed her because she’d hitched her skirt way up to look like a mini.”

“How did Betty take that?” Rachel wanted to know.

“I think she called and raised a couple of buttons on her blouse,” Chuck answered. “Naturally we drank a lot of coffee that flight and got to know the kid—her name’s Gwen—pretty well. By the time we reached Phoenix, Gwen was flopping all over the captain from behind, chewing at his ear and saying, ‘Tell me about those li’l bitty ol’ dials and buttons, honey. What’s that one over there?’ and she sorta hitched herself over his shoulder to point at the dial, so of course he nestled his head back between her breasts.”

“I bet the captain hated that,” I said.

“Not the captain—Betty. She came barging in yelling, ‘Get your hot pants outta here!’ I had to break up the slugfest. It’s something to see two dames stage a catfight. But that isn’t all.”

Chuck held up his wineglass for a refill. “On the return flight Betty had Gwen demonstrate the life vest and oxygen mask and . . .”

We didn’t let Chuck finish. I said, “Ammonia.” Rachel said, “Pepper.” The three of us burst into such wild laughter that the waiter thought we’d lost our minds. I was right. Betty put ammonia into the oxygen mask, Gwen took a deep breath to illustrate inhalation technique and the ammonia fumes all but killed her.

“You dames are something,” Chuck said with a sigh. “A guy has to be an idiot to get mixed up with any of you.”

That was our Christmas dinner. We forgot all about the rotten time in Rochester. For the moment we stopped thinking about Sally Lu. It was just good to be alive and able to laugh. After coffee Rachel said she had to dash. She raced off on an imaginary errand. Chuck and I went back to the apartment. We had very little time but we put it to the best possible use, the very best.

Who says there isn’t a Santa Claus?

CHAPTER XVIII

“The Saga of Sandy”

“Where does Sandy get the money to do all the things she does, Trudy?” Rachel asked one night as we were watching

Batman.

Batman.

“Beats me. Maybe she has a rich uncle.”

“I don’t think so.”

“How do you know?”

Other books

The Long Fall by Lynn Kostoff

Soulblade by Lindsay Buroker

Something Like Rain (Something Like... Book 8) by Jay Bell

If My Heart Could See You by , Sherry Ewing

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories by Connie Willis

Magnolia Blossoms by Rhonda Dennis

Kill My Darling by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Going to the Chapel by Janet Tronstad

The Boy Who Lost Fairyland by Catherynne M. Valente

Apple Pie Angel by Lynn Cooper