Colin Woodard (27 page)

Authors: American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America

Tags: #American Government, #General, #United States, #State, #Political Science, #History

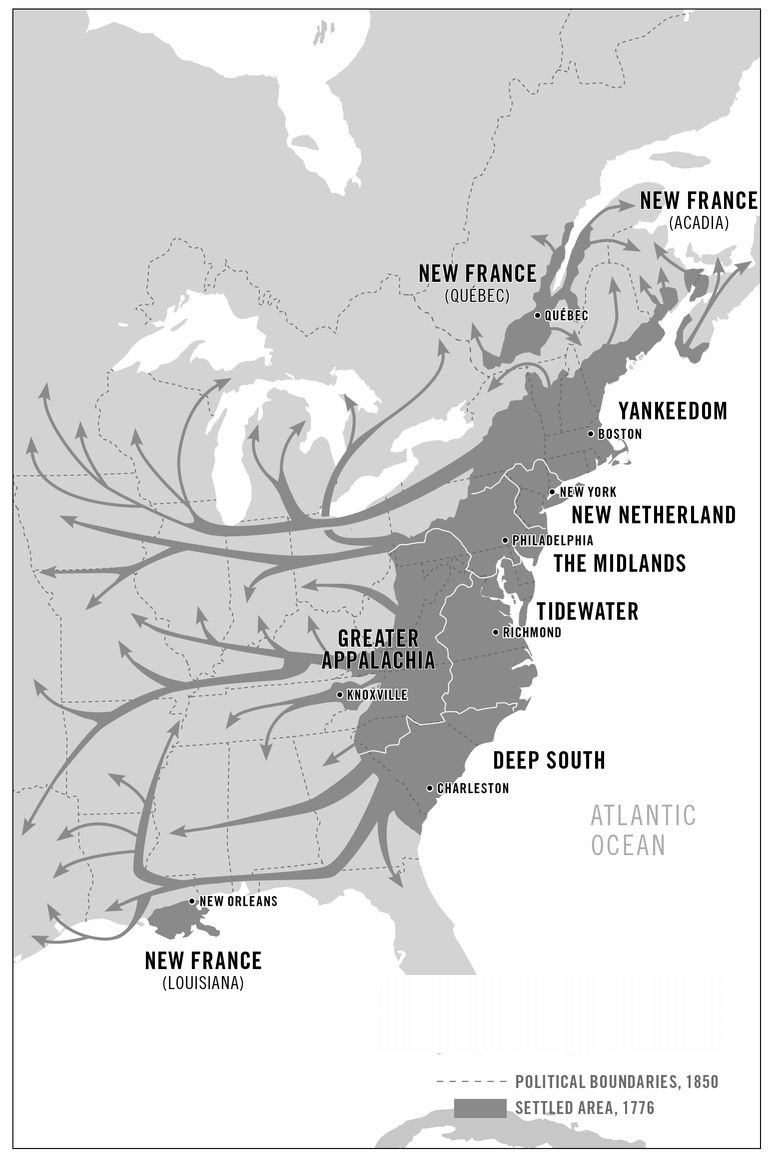

THE EASTERN NATIONS 1776â1850

Â

The states had relinquished any jurisdictional claims to Ohio and the rest of the upper Midwest in 1786, when these former Indian lands became part of the federal government's Northwest Territory. But Connecticut retained title to a three-million-acre strip of northern Ohioâits so-called Western Reserveâwhich was turned over to some of the same Boston speculators who had retailed out much of western New York. Another New England land company obtained a swath of the Muskingum Valley from the federal government. Both parcels were settled almost exclusively by Yankees.

True to form, the New Englanders tended to move west as communities. Entire families would pack their possessions, rendezvous with their neighbors, and journey en masse to their new destination, often led by their minister. On arrival they planted a new townânot just a collection of individual farmsâcomplete with a master plot plan with specific sites set aside for streets, the town green and commons, a Congregational or Presbyterian meeting house, and the all-important public school. They also brought the town meeting government model with them. In a culture that believed in communal freedom and local self-governance, a well-regulated town was the essential civic organism and the very definition of civilization.

Yankee settler groups often viewed their journey as an extension of New England's religious mission, a parallel to those undertaken by their forefathers in the early 1600s. The first group to depart Ipswich, Massachusetts, for the Muskingum Valley in 1787 paraded before the town meeting house to receive a farewell message from their minister modeled on the one the Pilgrims heard before leaving Holland. On the last leg of their journey, they constructed a flotilla of boats to float down the Ohio and named the flagship the

Mayflower of the West

. Similarly, before setting out to found Vermontville, Michigan, ten families in Addison County, Vermont, joined their Congregational minister in drawing up and signing a written constitution loosely modeled on the Mayflower Compact. “We believe that a pious and devoted emigration is to be one of the most efficient means in the hands of God, in removing the moral darkness which hangs over a great portion of the valley of the Mississippi,” the settlers declared before pledging to “rigidly observe the holy Sabbath” and to settle “in the same neighborhood with one another” to re-create “the same social and religious privileges we left behind.” In Granville, Massachusetts, settlers drew up a similar compact before undertaking the journey to create Granville, Ohio.

2

Mayflower of the West

. Similarly, before setting out to found Vermontville, Michigan, ten families in Addison County, Vermont, joined their Congregational minister in drawing up and signing a written constitution loosely modeled on the Mayflower Compact. “We believe that a pious and devoted emigration is to be one of the most efficient means in the hands of God, in removing the moral darkness which hangs over a great portion of the valley of the Mississippi,” the settlers declared before pledging to “rigidly observe the holy Sabbath” and to settle “in the same neighborhood with one another” to re-create “the same social and religious privileges we left behind.” In Granville, Massachusetts, settlers drew up a similar compact before undertaking the journey to create Granville, Ohio.

2

These New England outposts quickly dotted the map of the Western Reserve, their names revealing the origins of their Connecticut founders: Bristol, Danbury, Fairfield, Greenwich, Guilford, Hartford, Litchfield, New Haven, New London, Norwalk, Saybrook, and many more. Not surprisingly, people quickly started calling the region New Connecticut.

The Yankees consciously sought to extend New England culture across the upper Midwest. The emigrants aboard the

Mayflower of the West

were typical. On arrival in eastern Ohio, they founded the town of Marietta, and happily imposed taxes on themselves to fund the construction and operation of a school, church, and library. Nine years after their arrival, they founded the first of the Yankee Midwest's many New Englandâstyle colleges. Marietta College was headed by New Englandâborn Calvinist ministers and dedicated to “assiduously inculcating” the “essential doctrines and duties of the Christian religion.” Also, “No sectarian peculiarities of belief will be taught,” the founding trustees decreed. Similar colleges popped up wherever the Yankees spread, each a powerful outpost of cultural production: Oberlin and Case Western Reserve (in Ohio), Beloit and Olivet (in Michigan), Ripon and Madison (in Wisconsin), Carleton (Minnesota), Grinnell (Iowa), and Illinois College.

3

Mayflower of the West

were typical. On arrival in eastern Ohio, they founded the town of Marietta, and happily imposed taxes on themselves to fund the construction and operation of a school, church, and library. Nine years after their arrival, they founded the first of the Yankee Midwest's many New Englandâstyle colleges. Marietta College was headed by New Englandâborn Calvinist ministers and dedicated to “assiduously inculcating” the “essential doctrines and duties of the Christian religion.” Also, “No sectarian peculiarities of belief will be taught,” the founding trustees decreed. Similar colleges popped up wherever the Yankees spread, each a powerful outpost of cultural production: Oberlin and Case Western Reserve (in Ohio), Beloit and Olivet (in Michigan), Ripon and Madison (in Wisconsin), Carleton (Minnesota), Grinnell (Iowa), and Illinois College.

3

In this way, the Yankees laid down the cultural infrastructure of a large part of Ohio, portions of Iowa and Illinois, and almost the entirety of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. They had near-total control over politics in the latter three states for much of the nineteenth century. Five of the first six governors of Michigan were Yankees, and four had been born in New England. In Wisconsin, nine of the first twelve governors were Yankees, and all the rest were either New Netherlanders or foreign-born. (By contrast, in Illinoisâwhere Midlands and Appalachian cultures were in the majorityânot one of the first six governors was of Yankee descent; all had been born south of the Mason-Dixon line.) A third of Minnesota's first territorial legislature was New Englandâborn, and a great many of the rest were from upstate New York and the Yankee Midwest. In all three upper Great Lakes states, Yankees dominated discussions in the constitutional conventions and transplanted their legal, political, and religious norms. Across the Yankee Midwest, later settlersâbe they immigrants or transplants from the other American nationsâconfronted a dominant culture rooted in New England.

4

4

Nineteenth-century visitors often remarked on the difference between the areas north and south of the old National Road, an early highway that bisected Ohio and which is now called U.S. 40. North of the road, houses were said to be substantial and well maintained, with well-fed livestock outside and literate, well-schooled inhabitants within. Village greens, white church steeples, town hall belfries, and green-shuttered houses were the norm. South of the road, farm buildings were unpainted, the people were poorer and less educated, and the better homes were built with brick in Greco-Roman style. “As you travel north across Ohio,” Ohio State University dean Harlan Hatcher wrote in 1945, “you feel that you have been transported from Virginia into Connecticut.” There were exceptions (Yankees skipped over the marshlands of Indiana and northeastern Ohio en route to Michigan and Illinois), and between Appalachian “Virginia” and Yankee “Connecticut” one passed through a Midland transition zone. But the general observation holds true: the place we call “the Midwest” is actually divided into east-west cultural bands running all the way out to the Mississippi River and beyond.

5

5

Foreign immigrants to the Midwest often chose where to settle based on their degree of affinity or hostility to the dominant culture, and vice versa. The first major wave was German, and, not surprisingly, many of them joined their countrymen in the Midlands. Those who did not faced a choice between the Yankees and the Appalachian folk; few opted to settle in areas controlled by the latter.

Swedes and other Scandinavians, for their part, were comfortable with the Yankees, with whom they shared a commitment to frugality, sobriety, and civic responsibility; a hostility to slavery; and an acceptance of a staterun church. “The Scandinavians are the âNew Englanders' of the Old World,” a Congregational missionary in the Midwest informed his colleagues. “We can as confidently rely upon them to help American Christians rightly [make] . . . âAmerica for Christ' as we can rely upon the good

old

stock of Massachusetts.”

6

old

stock of Massachusetts.”

6

Other groups who fundamentally disagreed with New England values avoided the region on account of the Yankees' reputation for minding other people's business and pressuring newcomers to conform to their cultural norms. Catholicsâwhether Irish, south German, or Italianâdid not appreciate the Yankee educational system, correctly recognizing that the schools were designed to assimilate their children into Yankee culture. In areas where Catholic immigrants cohabitated with Yankees, the newcomers created their own parallel system of parochial schools precisely to protect their children from the Yankee mold. Yankees often reacted with hostility, denouncing Catholic immigrants as unwitting tools of a Vaticandirected conspiracy to bring down the republic. Whenever possible, Catholic immigrants chose to live in the more tolerant, multicultural Midlands or in individualistic Appalachia, where moral crusaders were looked upon as self-righteous and irritating. Even German Protestants found themselves at odds with their Yankee neighbors, who would try to pressure them into giving up their brewing traditions and beer gardens in favor of a solemn, austere observance of the Sabbath. Multiculturalism wouldn't become a Yankee hallmark until much later, after Puritan values ceased to be seen as essential to promoting the common good.

7

7

Political scientists investigating voting patterns have probed electoral records dating back to the early nineteenth century, matching pollingplace returns with demographic information about each precinct. The results have been startling. Previous assumptions about class or occupation being the key factors influencing voter choices have turned out to be completely wrong, with the nineteenth-century Midwest providing some of the most intriguing evidence that ethnographic origins trumped all other considerations from 1850 onward. Poor white German Catholic miners in northern Wisconsin tended to vote entirely differently from poor white English Methodist miners in the same area. English Congregationalists tended to vote alike regardless of whether they lived in cities or on farms. Scandinavian immigrants voted with native-born Yankees in opposition to candidates and policies preferred by immigrant Irish Catholics or native-born Southern Baptists of Appalachian origin.

8

8

As the nation careened toward civil war in the 1850s, areas first settled by Yankees gravitated to the new Republican Party. Counties dominated by immigrants from New England or Scandinavia were the strongest Republican supporters, generally backed by German Protestants. This made Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota reliably Republican straight through the mid-twentieth century; the other states split along national lines. Later, when the Republicans became champions in the fight against civil rights, Yankee-dominated states and counties in the Midwest flipped en masse to the Democrats, just as their colleagues in New England did. The outlines of the Western Reserve are still visible on a county-by-county map of the 2000, 2004, or 2008 presidential elections.

While much of the upper Midwest is indeed part of Greater Yankeedom, its greatest city is not. Chicago, founded by Yankees around Fort Dearborn in the 1830s, quickly took on the role of a border city, a grand trading entrepôt and transportation hub on the boundary of the Yankee and Midland Wests. New Englanders were influential early on, establishing institutions such as the Field Museum (named for Marshall Field of Conway, Massachusetts), the Newberry Library (for Walter Newberry of Connecticut), the

Chicago Democrat

and

Inter Ocean

newspapers, and the Chicago Theological Institute. But New Englanders were soon overwhelmed by new arrivals from Europe, the Midlands, Appalachia, and beyond. Purists fled north to found the very Yankee suburb of Evanston. Other Yankees looked disapprovingly upon the brash, unruly, multi-ethnic metropolis. By the 1870 census, New England natives comprised just one-thirtieth of the city's population.

9

Chicago Democrat

and

Inter Ocean

newspapers, and the Chicago Theological Institute. But New Englanders were soon overwhelmed by new arrivals from Europe, the Midlands, Appalachia, and beyond. Purists fled north to found the very Yankee suburb of Evanston. Other Yankees looked disapprovingly upon the brash, unruly, multi-ethnic metropolis. By the 1870 census, New England natives comprised just one-thirtieth of the city's population.

9

Â

However assiduously New Englanders had set out to transform the frontier, they themselves were also transformed by it. Yankee culture may have maintained its underlying zeal to improve the world, setting it on the path toward the secular Puritanism of the present day, but it was stripped of its commitment to religious orthodoxy.

On the frontier, many Yankees would remain true to the Congregational faith or its near-cousin Presbyterianism, but others experienced a religious conversion. An essentially theocratic society, New England produced an unusual number of intense religious personalitiesâpeople, in the words of the late historian Frederick Merk, “eager to get into direct touch with God, to see God in person, to hear His voice from on high.” In the tightly controlled Yankee homeland, mystics and self-declared prophets generally were kept in check, but out on the frontier, the enforcement of orthodoxy was laxer. The result was an explosion of new religions, starting in western New York, where religious fervor was so incendiary that people started calling it the “Burnt-over District.”

10

10

Many religions came into being, but nearly all of them sought to restore the primitive simplicity of the early Christian faith before it accreted elaborate institutions, a written canon, and a bevy of clerical authorities. If Lutherans, Calvinists, or Methodists had sought to bring people closer to God by eliminating the upper levels of ecclesiastical hierarchy (archbishops, cardinals, and the Vatican), these new evangelicals took things several steps further, removing the middle ranks almost entirely. People were to contact God directly and personally, and would become born again when they did so. They were to seek their own path to the divine, guided by one or more trailblazers who allegedly enjoyed unusually good communication with their maker. Like the prophets, these charismatic leaders believed they had been personally contacted by God and shown the true path to salvation.

Other books

Tommo & Hawk by Bryce Courtenay

Jenna Starborn by Sharon Shinn

The Love Market by Mason, Carol

Haiku by Stephen Addiss

Dead Souls by J. Lincoln Fenn

City of Strangers (Luis Chavez Book 2) by Mark Wheaton

Nemo and the Surprise Party by Disney Book Group

Fiendish Schemes by K. W. Jeter

Fighting for Flight by JB Salsbury

Game On (The Bod Squad Series Book 1) by Gabra Zackman