Complaint: From Minor Moans to Principled Protests (16 page)

Read Complaint: From Minor Moans to Principled Protests Online

Authors: Julian Baggini

The grievance culture is a weed which has driven out its fairer relative, moral complaint. There are other ways of trying to prune it, but if we want to attack it at its roots, we need the soil of ethics, not law.

I said at the beginning of this book that my aim was to counter the perception we have of complaint as negative, trivial and largely pointless with the idea that it can be a positive, constructive force, springing from the very essence of what makes us human. At its noblest, complaint – as a directed expression of a refusal or inability to accept that things are not as they ought to be – lies at the very heart of all campaigns to create a better, more just world. At its worst, wrong complaint is manifest in a grievance culture which undermines ethics and replaces it with a legalistic set of attitudes which undermines responsibility, freedom and a proper sense of life’s contingencies.

But even at a less grand level, being more sensitive to the difference between right and wrong complaint can make numerous small differences to our lives. It can be a terrible waste of energy to complain about those things which either cannot or should not be changed. Inevitably, many if not most of our complaints are of this kind, but as long as we accept that venting our spleens in such cases is no more than a cathartic release, or even a leisure activity we enjoy, this is not a problem. Troubles arise when such complaints lead to frustration and stress as we fail to realise the functional pointlessness of our protests.

It is also helpful to be more conscious of the manner, as well as of the matter, of our complaining. There is no requirement for complaints to be born of anger, or for them to be made rudely. The art of constructive complaint requires knowing when a calm approach is more likely to restore things to how

they ought to be, and when a flying rage is the only thing likely to force the issue. It also requires being specific and proportionate in what we complain about.

There is also some value in reflecting on what our complaints say about ourselves, as individuals as well as generations, nations and perhaps sexes: you shall know us by our complaints. Complaint is not unique in this respect: to a certain degree, almost anything we say or do in particular reflects something more general. But complaint seems to me to be particularly revealing and interesting, partly because it is not usually considered worthy of serious examination and partly because complaining is one of the most human things we do.

It is this which, I think, makes complaint so important. So much of life is about dealing with the gap between how things are and how we think they ought to be. How much imperfection must we accept, and how much should we strive to change? It’s a question we face every day, with jobs, friends, partners, our bodies and minds, and in politics and social justice. It is hardly a distortion to say that such questions are effectively about whether we should complain or persevere, about whether we direct our dissatisfaction at others or whether we need to take responsibility ourselves, and how we put these decisions into practice.

General policies are no substitute here for wise judgement. People who habitually keep their complaints to themselves can be even harder to deal with than those who complain too much: at least with the latter you know what they think. However, having thought about the nature of right and wrong complaint at least gives us the background to make more reflective judgements.

Do not, then, believe those who say we would do better to

complain less, not only because these are often the very people who have most to gain by the status quo being unchallenged but also because it is the quality rather than the quantity of our complaining which counts. To echo Martin Luther King, I do not therefore say ‘Get rid of your discontent’. Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channelled into the creative outlet of constructive, positive complaint and action to bring the world closer to how it ought to be.

THE COMPLAINT SURVEY

The survey I discuss in

Chapter 4

was conducted at this book’s web site,

www.thecomplaintbook.com

. Of the many people who took the survey, only the results of the 920 who completed all of it have been used in the analysis. This appendix includes a partial summary of the main results.

This is what is known as a self-selecting survey, which means that people were not selected to reflect a representative spread of the population but volunteered themselves to answer questions. As such, they are highly unreliable in many respects. Most importantly, the brute totals recorded by the survey should not be taken as an accurate reflection of the population as a whole.

Nevertheless, such surveys can be more indicative of general trends when you look at

relative

answers. For example, it would be unlikely (but not impossible) if the variations in responses which emerge only when you factor in age were artefacts of anything other than age. Whatever the social mix of people who took the survey, if older participants responded systematically differently from younger ones, then that difference is probably a product of either age per se or of shifts in values and beliefs that have occurred between generations. Hence in presenting these results I have in general given relative, not absolute, data.

One final caveat: it is not my belief that any claim made in this book is proven or even made likely by this survey. At most it suggests things which may be true, but whether those things are right is something we must either judge for ourselves or find the harder evidence to back it up.

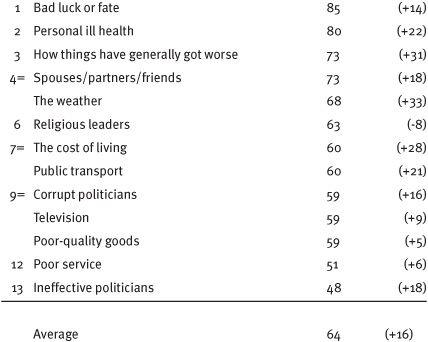

Table 1: What do people complain about most?

Participants were asked to say whether they ‘complain very regularly’, ‘complain quite oft en’, ‘complain from time to time’ or ‘rarely complain’ about thirteen common subjects for complaint. The resulting ‘complaint factor’ is represented as a percentage, where 100 would represent all participants saying they complained very regularly and 0 saying they rarely complained. The number in brackets represents the difference in the complaint factor compared with results when people were asked what they thought

other people

in their country complained about. In every case but one, people judged their own level of complaint to be higher than that of others. The only thing people thought others complained about more than they did themselves was ‘religious leaders’.

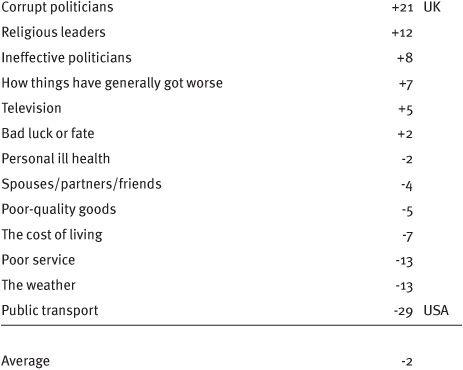

Table 2: What do people complain about in the UK and USA?

Figures here represent the difference in ‘complaint factor’ scores (calculated as for

Table 1

) between the USA and the UK, where a plus score indicates a higher UK level of complaint and a minus score a higher level of US complaint. Note that although there are wide variations on specific complaints, the average is remarkably similar.

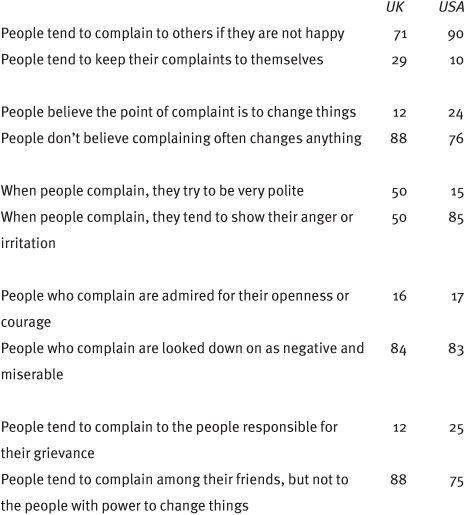

Table 3: How do people complain in the UK and USA?

Figures here represent the percentage of respondents who chose the statement as being more true of their country than the alternative in the pair.

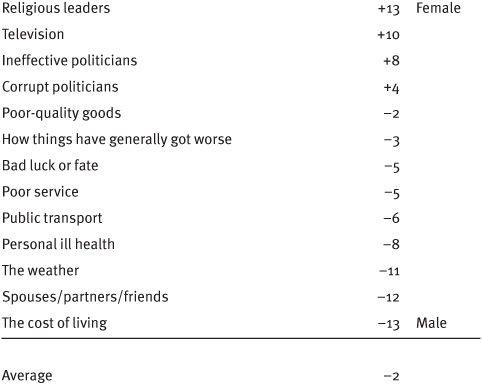

Table 4: What do men and women complain about?

Figures here represent the difference in scores (calculated as for

Table 1

) between men and women, where a plus score indicates a higher female level of complaint and a minus score a higher level of male complaint. Note that there is less variation here than there is in

Table 2

, which compared national differences. Note also how the average level of complaint is again very similar.

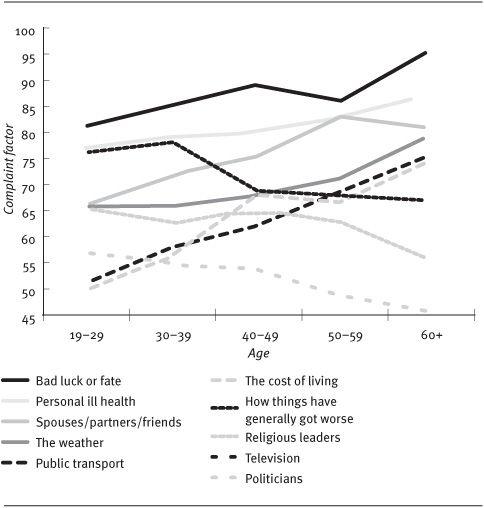

Table 5: What difference does age make?

This graph shows how levels of self-reported complaint varied with age for those subjects where clear trends were evident. The two types of complaint about politicians have been combined into one for this graph. The thick grey line running through the middle is the average complaint factor.

Epicurus,

The Epicurus Reader: Selected Writings and Testimonia

(Hackett, 1994)

Desiderius Erasmus,

The Complaint of Peace

(1517)

David Walter Hall,

The Last Priest

(Lulu.com, 2007)

Charles F. Hanna, ‘Complaint as a Form of Association’,

Qualitative Sociology

, vol. 4, no. 4 (December 1981)

Robert Hughes,

Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America

(Oxford University Press, 1993)

Martin Luther King,

A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr

., ed. Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard (Warner Books, 2002)

Jack Kornfield (ed.),

Teachings of the Buddha

(Shambhala Publications, 1996)

Robin M. Kowalski, ‘Complaints, and Complaining: Functions, Antecedents and Consequences’,

Psychological Bulletin

, vol. 119, no. 2 (1996)