Complete Works of Emile Zola (926 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

Sandoz, who had grown pale, watched the large ruddy coils of smoke rolling in the wind.

‘It was fated,’ he mused in an undertone. ‘Our excessive activity and pride of knowledge were bound to cast us back into doubt. This century, which has already thrown so much light over the world, was bound to finish amid the threat of a fresh flow of darkness — yes, our discomfort comes from that! Too much has been promised, too much has been hoped for; people have looked forward to the conquest and explanation of everything, and now they growl impatiently. What! don’t things go quicker than that? What! hasn’t science managed to bring us absolute certainty, perfect happiness, in a hundred years? Then what is the use of going on, since one will never know everything, and one’s bread will always be as bitter? It is as if the century had become bankrupt, as if it had failed; pessimism twists people’s bowels, mysticism fogs their brains; for we have vainly swept phantoms away with the light of analysis, the supernatural has resumed hostilities, the spirit of the legends rebels and wants to conquer us, while we are halting with fatigue and anguish. Ah! I certainly don’t affirm anything; I myself am tortured. Only it seems to me that this last convulsion of the old religious terrors was to be foreseen. We are not the end, we are but a transition, a beginning of something else. It calms me and does me good to believe that we are marching towards reason, and the substantiality of science.’

His voice had become husky with emotion, and he added:

‘That is, unless madness plunges us, topsy-turvy, into night again, and we all go off throttled by the ideal, like our old friend who sleeps there between his four boards.’

The hearse was leaving transversal Avenue No. 2 to turn, on the right, into lateral Avenue No. 3, and the painter, without speaking, called the novelist’s attention to a square plot of graves, beside which the procession was now passing.

There was here a children’s cemetery, nothing but children’s tombs, stretching far away in orderly fashion, separated at regular intervals by narrow paths, and looking like some infantile city of death. There were tiny little white crosses, tiny little white railings, disappearing almost beneath an efflorescence of white and blue wreaths, on a level with the soil; and that peaceful field of repose, so soft in colour, with the bluish tint of milk about it, seemed to have been made flowery by all the childhood lying in the earth. The crosses recorded various ages, two years, sixteen months, five months. One poor little cross, destitute of any railing, was out of line, having been set up slantingly across a path, and it simply bore the words: ‘Eugenie, three days.’ Scarcely to exist as yet, and withal to sleep there already, alone, on one side, like the children who on festive occasions dine at a little side table!

However, the hearse had at last stopped, in the middle of the avenue; and when Sandoz saw the grave ready at the corner of the next division, in front of the cemetery of the little ones, he murmured tenderly:

‘Ah! my poor old Claude, with your big child’s heart, you will be in your place beside them.’

The under-bearers removed the coffin from the hearse. The priest, who looked surly, stood waiting in the wind; some sextons were there with their shovels. Three neighbours had fallen off on the road, the ten had dwindled into seven. The second cousin, who had been holding his hat in his hand since leaving the church, despite the frightful weather, now drew nearer. All the others uncovered, and the prayers were about to begin, when a loud piercing whistle made everybody look up.

Beyond this corner of the cemetery as yet untenanted, at the end of lateral Avenue No. 3, a train was passing along the high embankment of the circular railway which overlooked the graveyard. The grassy slope rose up, and a number of geometrical lines, as it were, stood out blackly against the grey sky; there were telegraph-posts, connected by thin wires, a superintendent’s box, and a red signal plate, the only bright throbbing speck visible. When the train rolled past, with its thunder-crash, one plainly distinguished, as on the transparency of a shadow play, the silhouettes of the carriages, even the heads of the passengers showing in the light gaps left by the windows. And the line became clear again, showing like a simple ink stroke across the horizon; while far away other whistles called and wailed unceasingly, shrill with anger, hoarse with suffering, or husky with distress. Then a guard’s horn resounded lugubriously.

‘

Revertitur in terram suam unde erat

,’ recited the priest, who had opened a book and was making haste.

But he was not heard, for a large engine had come up puffing, and was manoeuvring backwards and forwards near the funeral party. It had a loud thick voice, a guttural whistle, which was intensely mournful. It came and went, panting; and seen in profile it looked like a heavy monster. Suddenly, moreover, it let off steam, with all the furious blowing of a tempest.

‘

Requiescat in pace

,’ said the priest.

‘Amen,’ replied the choirboy.

But the words were again lost amid the lashing, deafening detonation, which was prolonged with the continuous violence of a fusillade.

Bongrand, quite exasperated, turned towards the engine. It became silent, fortunately, and every one felt relieved. Tears had risen to the eyes of Sandoz, who had already been stirred by the words which had involuntarily passed his lips, while he walked behind his old comrade, talking as if they had been having one of their familiar chats of yore; and now it seemed to him as if his youth were about to be consigned to the earth. It was part of himself, the best part, his illusions and his enthusiasm, which the sextons were taking away to lower into the depths. At that terrible moment an accident occurred which increased his grief. It had rained so hard during the preceding days, and the ground was so soft, that a sudden subsidence of soil took place. One of the sextons had to jump into the grave and empty it with his shovel with a slow rhythmical movement. There was no end to the matter, the funeral seemed likely to last for ever amid the impatience of the priest and the interest of the four neighbours who had followed on to the end, though nobody could say why. And up above, on the embankment, the engine had begun manoeuvring again, retreating and howling at each turn of its wheels, its fire-box open the while, and lighting up the gloomy scene with a rain of sparks.

At last the pit was emptied, the coffin lowered, and the aspergillus passed round. It was all over. The second cousin, standing erect, did the honours with his correct, pleasant air, shaking hands with all these people whom he had never previously seen, in memory of the relative whose name he had not remembered the day before.

‘That linen-draper is a very decent fellow,’ said Bongrand, who was swallowing his tears.

‘Quite so,’ replied Sandoz, sobbing.

All the others were going off, the surplices of the priest and the choirboy disappeared between the green trees, while the straggling neighbours loitered reading the inscriptions on the surrounding tombs.

Then Sandoz, making up his mind to leave the grave, which was now half filled, resumed:

‘We alone shall have known him. There is nothing left of him, not even a name!’

‘He is very happy,’ said Bongrand; ‘he has no picture on hand, in the earth where he sleeps. It is as well to go off as to toil as we do merely to turn out infirm children, who always lack something, their legs or their head, and who don’t live.’

‘Yes, one must really be wanting in pride to resign oneself to turning out merely approximate work and resorting to trickery with life. I, who bestow every care on my books — I despise myself, for I feel that, despite all my efforts, they are incomplete and untruthful.’

With pale faces, they slowly went away, side by side, past the children’s white tombs, the novelist then in all the strength of his toil and fame, the painter declining but covered with glory.

‘There, at least, lies one who was logical and brave,’ continued Sandoz; ‘he confessed his powerlessness and killed himself.’

‘That’s true,’ said Bongrand; ‘if we didn’t care so much for our skins we should all do as he has done, eh?’

‘Well, yes; since we cannot create anything, since we are but feeble copyists, we might as well put an end to ourselves at once.’

Again they found themselves before the burning pile of old rotten coffins, now fully alight, sweating and crackling; but there were still no flames to be seen, the smoke alone had increased — a thick acrid smoke, which the wind carried along in whirling coils, so that it now covered the whole cemetery as with a cloud of mourning.

‘Dash it! Eleven o’clock!’ said Bongrand, after pulling out his watch. ‘I must get home again.’

Sandoz gave an exclamation of surprise:

‘What, already eleven?’

Over the low-lying graves, over the vast bead-flowered field of death, so formal of aspect and so cold, he cast a long look of despair, his eyes still bedimmed by his tears. And then he added:

‘Let’s go to work.’

THE END

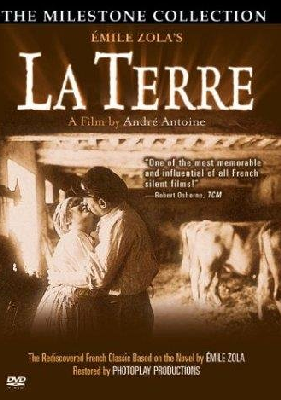

THE EARTH

Translated by Ernest Alfred Vizetelly

Published in 1887 in

Le Figaro

,

La Terre

is set in a rural community in the Beauce, an area of central France. The novel features Jean Macquart, whose childhood in the south of France was recounted in

La Fortune des Rougon

, and who will go on to appear prominently in the later novel

La Débâcle

.

La Terre

describes the steady disintegration of a family of agricultural workers in Second Empire France, in the years immediately before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Offering a vivid description of the hardships and brutality of rural life in the late nineteenth century, it is a powerful work of naturalist fiction and is considered among the author’s greatest achievements.

The novel portrays Jean Macquart as an itinerant farm worker, who has come to Rognes to work as a day labourer. Although he had been a corporal in the French Army and a veteran of the Battle of Solferino, he now must undergo menial work to earn his bread. In time Macquart begins to court a local girl, Françoise Mouche, who lives in the village with her sister Lise. However, Lise is married to Buteau, a sinister man from the village, who is attracted to both sisters.

A view of the Beauce area — the setting of the novel

CONTENTS

CHAPTER VI