Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (121 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

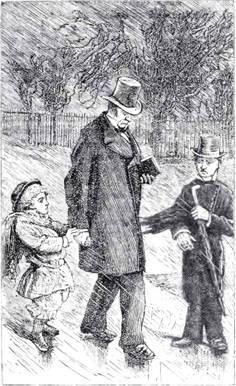

The page stood stock-still in astonishment for an instant — then pulled the new silk umbrella from under his arm, and turned the corner in a violent hurry. His suspicions had not deceived him. There was Mr. Thorpe himself walking sternly homeward through the rain, before church was over. He led by the hand “Master Zack,” who was trotting along under protest, with his hat half off his head, hanging as far back from his father’s side as he possibly could, and howling all the time at the utmost pitch of a very powerful pair of lungs.

Mr. Thorpe stopped as he passed the page, and snatched the umbrella out of Snoxell’s hand, with unaccustomed impetuity; said sharply, “Go to your mistress, go on to the church;” and then resumed his road home, dragging his son after him faster than ever.

“Snoxy! Snoxy!” screamed Master Zack, turning round towards the page, so that he tripped himself up and fell against his father’s legs at every third step; “I’ve been a naughty boy at church!”

“Ah! you look like it, you do,” muttered Snoxell to himself sarcastically, as he went on. With that expression of opinion, the page approached the church portico, and waited sulkily among his fellow servants and their umbrellas for the congregation to come out.

When Mr. Goodworth and Mrs. Thorpe left the church, the old gentleman, regardless of appearances, seized eagerly on the despised gingham umbrella, because it was the largest he could get, and took his daughter home under it in triumph. Mrs. Thorpe was very silent, and sighed dolefully once or twice, when her father’s attention wandered from her to the people passing along the street.

“You’re fretting about Zack,” said the old gentleman, looking round suddenly at his daughter. “Never mind! leave it to me. I’ll undertake to beg him off this time.”

“It’s very disheartening and shocking to find him behaving so,” said Mrs. Thorpe, “after the careful way we’ve brought him up in, too!”

“Nonsense, my love! No, I don’t mean that — I beg your pardon. But who can be surprised that a child of six years old should be tired of a sermon forty minutes long by my watch? I was tired of it myself I know, though I wasn’t candid enough to show it as the boy did. There! there! we won’t begin to argue: I’ll beg Zack off this time, and we’ll say no more about it.”

Mr. Goodworth’s announcement of his benevolent intentions towards Zack seemed to have very little effect on Mrs. Thorpe; but she said nothing on that subject or any other during the rest of the dreary walk home, through rain, fog, and mud, to Baregrove Square.

Rooms have their mysterious peculiarities of physiognomy as well as men. There are plenty of rooms, all of much the same size, all furnished in much the same manner, which, nevertheless, differ completely in expression (if such a term may be allowed) one from the other; reflecting the various characters of their inhabitants by such fine varieties of effect in the furniture-features generally common to all, as are often, like the infinitesimal varieties of eyes, noses, and mouths, too intricately minute to be traceable. Now, the parlor of Mr. Thorpe’s house was neat, clean, comfortably and sensibly furnished. It was of the average size. It had the usual side-board, dining-table, looking-glass, scroll fender, marble chimney-piece with a clock on it, carpet with a drugget over it, and wire window-blinds to keep people from looking in, characteristic of all respectable London parlors of the middle class. And yet it was an inveterately severe-looking room — a room that seemed as if it had never been convivial, never uproarious, never anything but sternly comfortable and serenely dull — a room which appeared to be as unconscious of acts of mercy, and easy unreasoning over-affectionate forgiveness to offenders of any kind — juvenile or otherwise — as if it had been a cell in Newgate, or a private torturing chamber in the Inquisition. Perhaps Mr. Goodworth felt thus affected by the parlor (especially in November weather) as soon as he entered it — for, although he had promised to beg Zack off, although Mr. Thorpe was sitting alone by the table and accessible to petitions, with a book in his hand, the old gentleman hesitated uneasily for a minute or two, and suffered his daughter to speak first.

“Where is Zack?” asked Mrs. Thorpe, glancing quickly and nervously all round her.

“He is locked up in my dressing-room,” answered her husband without taking his eyes off the book.

“In your dressing-room!” echoed Mrs. Thorpe, looking as startled and horrified as if she had received a blow instead of an answer; “in your dressing-room! Good heavens, Zachary! how do you know the child hasn’t got at your razors?”

“They are locked up,” rejoined Mr. Thorpe, with the mildest reproof in his voice, and the mournfullest self-possession in his manner. “I took care before I left the boy, that he should get at nothing which could do him any injury. He is locked up, and will remain locked up, because” —

“I say, Thorpe! won’t you let him off this time?” interrupted Mr. Goodworth, boldly plunging head foremost, with his petition for mercy, into the conversation.

“If you had allowed me to proceed, sir,” said Mr. Thorpe, who always called his father-in-law

Sir,

“I should have simply remarked that, after having enlarged to my son (in such terms, you will observe, as I thought best fitted to his comprehension) on the disgrace to his parents and himself of his behavior this morning, I set him as a task three verses to learn out of the ‘Select Bible Texts for Children;’ choosing the verses which seemed most likely, if I may trust my own judgment on the point, to impress on him what his behavior ought to be for the future in church. He flatly refused to learn what I told him. It was, of course, quite impossible to allow my authority to be set at defiance by my own child (whose disobedient disposition has always, God knows, been a source of constant trouble and anxiety to me); so I locked him up, and locked up he will remain until he has obeyed me. My dear,” (turning to his wife and handing her a key), “I have no objection, if you wish, to your going and trying what

you

can do towards overcoming the obstinacy of this unhappy child.”

Mrs. Thorpe took the key, and went up stairs immediately — went up to do what all women have done, from the time of the first mother; to do what Eve did when Cain was wayward in his infancy, and cried at her breast — in short, went up to coax her child.

Mr. Thorpe, when his wife closed the door, carefully looked down the open page on his knee for the place where he had left off — found it — referred back a moment to the last lines of the preceding leaf — and then went on with his book, not taking the smallest notice of Mr. Goodworth.

“Thorpe!” cried the old gentleman, plunging head-foremost again, into his son-in-law’s reading this time instead of his talk, “You may say what you please; but your notion of bringing up Zack is a wrong one altogether.”

With the calmest imaginable expression of face, Mr. Thorpe looked up from his book; and, first carefully putting a paper-knife between the leaves, placed it on the table. He then crossed one of his legs over the other, rested an elbow on each arm of his chair, and clasped his hands in front of him. On the wall opposite hung several lithographed portraits of distinguished preachers, in and out of the Establishment — mostly represented as very sturdily-constructed men with bristly hair, fronting the spectator interrogatively and holding thick books in their hands. Upon one of these portraits — the name of the original of which was stated at the foot of the print to be the Reverend Aaron Yollop — Mr. Thorpe now fixed his eyes, with a faint approach to a smile on his face (he never was known to laugh), and with a look and manner which said as plainly as if he had spoken it: “This old man is about to say something improper or absurd to me; but he is my wife’s father, it is my duty to bear with him, and therefore I am perfectly resigned.”

“It’s no use looking in that way, Thorpe,” growled the old gentleman; “I’m not to be put down by looks at my time of life. I may have my own opinions I suppose, like other people; and I don’t see why I shouldn’t express them, especially when they relate to my own daughter’s boy. It’s very unreasonable of me, I dare say, but I think I ought to have a voice now and then in Zack’s bringing up.”

Mr. Thorpe bowed respectfully — partly to Mr. Goodworth, partly to the Reverend Aaron Yollop. “I shall always be happy, sir, to listen to any expression of your opinion — ”

“My opinion’s this,” burst out Mr. Goodworth. “You’ve no business to take Zack to church at all, till he’s some years older than he is now. I don’t deny that there may be a few children, here and there, at six years old, who are so very patient, and so very — (what’s the word for a child that knows a deal more than he has any business to know at his age? Stop! I’ve got it! —

precocious

— that’s the word) — so very patient and so very precocious that they will sit quiet in the same place for two hours; making believe all the time that they understand every word of the service, whether they really do or not. I don’t deny that there may be such children, though I never met with them myself, and should think them all impudent little hypocrites if I did! But Zack isn’t one of that sort: Zack’s a genuine child (God bless him)! Zack — ”

“Do I understand you, my dear sir,” interposed Mr. Thorpe, sorrowfully sarcastic, “to be praising the conduct of my son in disturbing the congregation, and obliging me to take him out of church?”

“Nothing of the sort,” retorted the old gentleman; “I’m not praising Zack’s conduct, but I

am

blaming yours. Here it is in plain words: —

You

keep on cramming church down his throat; and

he

keeps on puking at it as if it was physic, because he don’t know any better, and can’t know any better at his age. Is that the way to make him take kindly to religious teaching? I know as well as you do, that he roared like a young Turk at the sermon. And pray what was the subject of the sermon? Justification by Faith. Do you mean to tell me that he, or any other child at his time of life, could understand anything of such a subject as that; or get an atom of good out of it? You can’t — you know you can’t! I say again, it’s no use taking him to church yet; and what’s more, it’s worse than no use, for you only associate his first ideas of religious instruction with everything in the way of restraint and discipline and punishment that can be most irksome to him. There! that’s my opinion, and I should like to hear what you’ve got to say against it?”

“Latitudinarianism,” said Mr. Thorpe, looking and speaking straight at the portrait of the Reverend Aaron Yollop.

“You can’t fob me off with long words, which I don’t understand, and which I don’t believe you can find in Johnson’s Dictionary,” continued Mr. Goodworth doggedly. “You would do much better to take my advice, and let Zack go to church, for the present, at his mother’s knees. Let his Morning Service be about ten minutes long; let your wife tell him, out of the New Testament, about Our Savior’s goodness and gentleness to little children; and then let her teach him, from the Sermon on the Mount, to be loving and truthful and forbearing and forgiving, for Our Savior’s sake. If such precepts as those are enforced — as they may be in one way or another — by examples drawn from his own daily life; from people around him; from what he meets with and notices and asks about, out of doors and in — mark my words, he’ll take kindly to his religious instruction. I’ve seen that in other children: I’ve seen it in my own children, who were all brought up so. Of course, you don’t agree with me! Of course you’ve got another objection all ready to bowl me down with?”

“Rationalism,” said Mr. Thorpe, still looking steadily at the lithographed portrait of the Reverend Aaron Yollop.

“Well, your objection’s a short one this time at any rate; and that’s a blessing!” said the old gentleman rather irritably. “Rationalism — eh? I understand that

ism,

I rather suspect, better than the other. It means in plain English, that you think I’m wrong in only wanting to give religious instruction the same chance with Zack which you let all other kinds of instruction have — the chance of becoming useful by being first made attractive. You can’t get him to learn to read by telling him that it will improve his mind — but you can by getting him to look at a picture book. You can’t get him to drink senna and salts by reasoning with him about its doing him good — but you can by promising him a lump of sugar to take after it. You admit this sort of principle so far, because you’re obliged; but the moment anybody wants (in a spirit of perfect reverence and desire to do good) to extend it to higher things, you purse up your lips, shake your head, and talk about Rationalism — as if that was an answer! Well! well! it’s no use talking — go your own way — I wash my hands of the business altogether. But now I

am

at it I’ll just say this one thing more before I’ve done: — your way of punishing the boy for his behavior in church is, in my opinion, about as bad and dangerous a one as could possibly be devised. Why not give him a thrashing, if you

must

punish the miserable little urchin for what’s his misfortune as much as his fault? Why not stop his pudding, or something of that sort? Here you are associating verses in the Bible, in his mind, with the idea of punishment and being locked up in the cold! You may make him get his text by heart, I dare say, by fairly tiring him out; but I tell you what I’m afraid you’ll make him learn too, if you don’t mind — you’ll make him learn to dislike the Bible as much as other boys dislike the birch-rod!”