Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2273 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

The first number, which appeared in January 1843, had not been quite finished when he wrote to me on the 8th of December: “The Chuzzlewit copy makes so much more than I supposed, that the number is nearly done. Thank God!” Beginning so hurriedly as at last he did, altering his course at the opening and seeing little as yet of the main track of his design, perhaps no story was ever begun by him with stronger heart or confidence. Illness kept me to my rooms for some days, and he was so eager to try the effect of Pecksniff and Pinch that he came down with the ink hardly dry on the last slip to read the manuscript to me. Well did Sydney Smith, in writing to say how very much the number had pleased him, foresee the promise there was in those characters. “Pecksniff and his daughters, and Pinch, are admirable — quite first-rate painting, such as no one but yourself can execute!” And let me here at once remark that the notion of taking Pecksniff for a type of character was really the origin of the book; the design being to show, more or less by every person introduced, the number and variety of humours and vices that have their root in selfishness.

Another piece of his writing that claims mention at the close of 1842 was a prologue contributed to the

Patrician’s Daughter

, Mr. Westland Marston’s first dramatic effort, which had attracted him by the beauty of its composition less than by the courage with which its subject had been chosen from the actual life of the time.

“Not light its import, and not poor its mien;

Yourselves the actors, and your homes the scene.”

This was the date, too, of Mr. Browning’s tragedy of the

Blot on the ‘Scutcheon

, which I took upon myself, after reading it in the manuscript, privately to impart to Dickens; and I was not mistaken in the belief that it would profoundly touch him. “Browning’s play,” he wrote (25th of November), “has thrown me into a perfect passion of sorrow. To say that there is anything in its subject save what is lovely, true, deeply affecting, full of the best emotion, the most earnest feeling, and the most true and tender source of interest, is to say that there is no light in the sun, and no heat in blood. It is full of genius, natural and great thoughts, profound and yet simple and beautiful in its vigour. I know nothing that is so affecting, nothing in any book I have ever read, as Mildred’s recurrence to that ‘I was so young — I had no mother.’ I know no love like it, no passion like it, no moulding of a splendid thing after its conception, like it. And I swear it is a tragedy that must be played; and must be played, moreover, by Macready. There are some things I would have changed if I could (they are very slight, mostly broken lines); and I assuredly would have the old servant

begin his tale upon the scene;

and be taken by the throat, or drawn upon, by his master, in its commencement. But the tragedy I never shall forget, or less vividly remember than I do now. And if you tell Browning that I have seen it, tell him that I believe from my soul there is no man living (and not many dead) who could produce such a work. — Macready likes the altered prologue very much.” . . . There will come a more convenient time to speak of his general literary likings, or special regard for contemporary books; but I will say now that nothing interested him more than successes won honestly in his own field, and that in his large and open nature there was no hiding-place for little jealousies. An instance occurs to me which may be named at once, when, many years after the present date, he called my attention very earnestly to two tales then in course of publication in

Blackwood’s Magazine

, and afterwards collected under the title of

Scenes of Clerical Life

. “Do read them,” he wrote. “They are the best things I have seen since I began my course.”

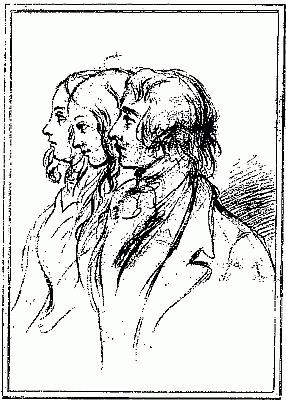

Maclise, R.A. C.H. Jeens.

Eighteen hundred and forty-three

opened with the most vigorous prosecution of his

Chuzzlewit

labour. “I hope the number will be very good,” he wrote to me of number two (8th of January). “I have been hammering away, and at home all day. Ditto yesterday; except for two hours in the afternoon, when I ploughed through snow half a foot deep, round about the wilds of Willesden.” For the present, however, I shall glance only briefly from time to time at his progress with the earlier portions of the story on which he was thus engaged until the midsummer of 1844. Disappointments arose in connection with it, unexpected and strange, which had important influence upon him: but, I reserve the mention of these for awhile, that I may speak of the leading incidents of 1843.

“I am in a difficulty,” he wrote (12th of February), “and am coming down to you some time to-day or to-night. I couldn’t write a line yesterday; not a word, though I really tried hard. In a kind of despair I started off at half-past two with my pair of petticoats to Richmond; and dined there!! Oh what a lovely day it was in those parts.” His pair of petticoats were Mrs. Dickens and her sister Georgina: the latter, since his return from America, having become part of his household, of which she remained a member until his death; and he had just reason to be proud of the steadiness, depth, and devotion of her friendship. In a note-book begun by him in January 1855, where, for the first time in his life, he jotted down hints and fancies proposed to be made available in future writings, I find a character sketched of which, if the whole was not suggested by his sister-in-law, the most part was applicable to her. “She — sacrificed to children, and sufficiently rewarded. From a child herself, always ‘the children’ (of somebody else) to engross her. And so it comes to pass that she is never married; never herself has a child; is always devoted ‘to the children’ (of somebody else); and they love her; and she has always youth dependent on her till her death — and dies quite happily.” Not many days after that holiday at Richmond, a slight unstudied outline in pencil was made by Maclise of the three who formed the party there, as we all sat together; and never did a touch so light carry with it more truth of observation. The likenesses of all are excellent; and I here preserve the drawing because nothing ever done of Dickens himself has conveyed more vividly his look and bearing at this yet youthful time. He is in his most pleasing aspect; flattered, if you will; but nothing that is known to me gives a general impression so life-like and true of the then frank, eager, handsome face.

It was a year of much illness with me, which had ever-helpful and active sympathy from him. “Send me word how you are,” he wrote, two days later. “But not so much for that I now write, as to tell you, peremptorily, that I insist on your wrapping yourself up and coming here in a hackney-coach, with a big portmanteau, to-morrow. It surely is better to be unwell with a Quick and Cheerful (and Co) in the neighbourhood, than in the dreary vastness of Lincoln’s-inn-fields. Here is the snuggest tent-bedstead in the world, and there you are with the drawing-room for your workshop, the Q and C for your pal, and ‘every-think in a concatenation accordingly.’ I begin to have hopes of the regeneration of mankind after the reception of Gregory last night, though I have none of the

Chronicle

for not denouncing the villain. Have you seen the note touching my

Notes

in the blue and yellow?”

The first of these closing allusions was to the editor of the infamous

Satirist

having been hissed from the Drury-lane stage, on which he had presented himself in the character of Hamlet; and I remember with what infinite pleasure I afterwards heard Chief Justice Tindal in court, charging the jury in an action brought by this malefactor against a publican of St. Giles’s for having paid men to take part in the hissing of him, avow the pride he felt in “living in the same parish with a man of that humble station of life of the defendant’s,” who was capable of paying money out of his own pocket to punish what he believed to be an outrage to decency. The second allusion was to a statement of the reviewer of the

American Notes

in the

Edinburgh

to the effect, that, if he had been rightly informed, Dickens had gone to America as a kind of missionary in the cause of international copyright; to which a prompt contradiction had been given in the

Times

. “I deny it,” wrote Dickens, “wholly. He is wrongly informed; and reports, without enquiry, a piece of information which I could only characterize by using one of the shortest and strongest words in the language.”

The disputes that had arisen out of the American book, I may add, stretched over great part of the year. It will quite suffice, however, to say here that the ground taken by him in his letters written on the spot, and printed in my former volume, which in all the more material statements his book invited public judgment upon and which he was moved to reopen in

Chuzzlewit

, was so kept by him against all comers, that none of the counter-statements or arguments dislodged him from a square inch of it. But the controversy is dead now; and he took occasion, on his later visit to America, to write its epitaph.

Though I did not, to revert to his February letter, obey its cordial bidding by immediately taking up quarters with him, I soon after joined him at a cottage he rented in Finchley; and here, walking and talking in the green lanes as the midsummer months were coming on, his introduction of Mrs. Gamp, and the uses to which he should apply that remarkable personage, first occurred to him. In his preface to the book he speaks of her as a fair representation, at the time it was published, of the hired attendant on the poor in sickness: but he might have added that the rich were no better off, for Mrs. Gamp’s original was in reality a person hired by a most distinguished friend of his own, a lady, to take charge of an invalid very dear to her; and the common habit of this nurse in the sick room, among other Gampish peculiarities, was to rub her nose along the top of the tall fender. Whether or not, on that first mention of her, I had any doubts whether such a character could be made a central figure in his story, I do not now remember; but if there were any at the time, they did not outlive the contents of the packet which introduced her to me in the flesh a few weeks after our return. “Tell me,” he wrote from Yorkshire, where he had been meanwhile passing pleasant holiday with a friend, “what you think of Mrs. Gamp? You’ll not find it easy to get through the hundreds of misprints in her conversation, but I want your opinion at once. I think you know already something of mine. I mean to make a mark with her.” The same letter enclosed me a clever and pointed little parable in verse which he had written for an annual edited by Lady Blessington.

Another allusion in the February letter reminds me of the interest which his old work for the

Chronicle

gave him in everything affecting its credit, and that this was the year when Mr. John Black ceased to be its editor, in circumstances reviving strongly all Dickens’s sympathies. “I am deeply grieved” (3rd of May, 1843) “about Black. Sorry from my heart’s core. If I could find him out, I would go and comfort him this moment.” He did find him out; and he and a certain number of us did also comfort this excellent man after a fashion extremely English, by giving him a Greenwich dinner on the 20th of May; when Dickens had arranged and ordered all to perfection, and the dinner succeeded in its purpose, as in other ways, quite wonderfully. Among the entertainers were Sheil and Thackeray, Fonblanque and Charles Buller, Southwood Smith and William Johnson Fox, Macready and Maclise, as well as myself and Dickens.

There followed another similar celebration, in which one of these entertainers was the guest and which owed hardly less to Dickens’s exertions, when, at the Star-and-garter at Richmond in the autumn, we wished Macready good-speed on his way to America. Dickens took the chair at that dinner; and with Stanfield, Maclise, and myself, was in the following week to have accompanied the great actor to Liverpool to say good-bye to him on board the Cunard ship, and bring his wife back to London after their leave-taking; when a word from our excellent friend Captain Marryat, startling to all of us except Dickens himself, struck him out of our party. Marryat thought that Macready might suffer in the States by any public mention of his having been attended on his way by the author of the

American Notes

and

Martin Chuzzlewit

, and our friend at once agreed with him. “Your main and foremost reason,” he wrote to me, “for doubting Marryat’s judgment, I can at once destroy. It has occurred to me many times; I have mentioned the thing to Kate more than once; and I had intended

not

to go on board, charging Radley to let nothing be said of my being in his house. I have been prevented from giving any expression to my fears by a misgiving that I should seem to attach, if I did so, too much importance to my own doings. But now that I have Marryat at my back, I have not the least hesitation in saying that I am certain he is right. I have very great apprehensions that the

Nickleby

dedication will damage Macready. Marryat is wrong in supposing it is not printed in the American editions, for I have myself seen it in the shop windows of several cities. If I were to go on board with him, I have not the least doubt that the fact would be placarded all over New York, before he had shaved himself in Boston. And that there are thousands of men in America who would pick a quarrel with him on the mere statement of his being my friend, I have no more doubt than I have of my existence. You have only doubted Marryat because it is impossible for

any man

to know what they are in their own country, who has not seen them there.”