Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (18 page)

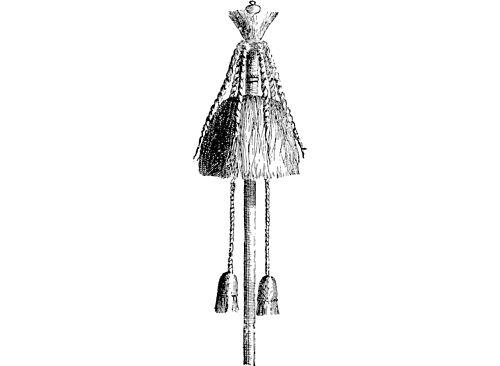

Horsetail banner: symbol of Ottoman authority

The mobilization for the season’s campaign was extraordinarily efficient. Within the Muslim heartlands it was not a press gang. Men came at the call to arms with a willingness that amazed European eyewitnesses such as George of Hungary, another prisoner in the empire at this time:

When recruiting for the army is begun, they gather with such readiness and speed you might think they are invited to a wedding not a war. They gather within a month in the order they are summoned, the infantrymen separately from the cavalrymen, all of them with their appointed chiefs, in the same order which they use for encampments and when preparing for battle… with such enthusiasm that men put themselves forward in the place of their neighbours, and those left at home feel an injustice has been done to them. They claim they will be happier if they die on the battlefield among the spears and arrows of the enemy than at home … Those who die in war like this are not mourned but are hailed as saints and victors, to be set as an example and given high respect.

‘Everyone who heard that the attack was to be against the City came running’, added Doukas, ‘both boys too young to march and old men bent double with age.’ They were fired by the prospect of booty and personal advancement and holy war, themes that were woven together in the Koran: by Islamic holy law, a city taken by force could be legitimately subjected to three days of plunder. Enthusiasm was made all the keener by knowledge of the objective: the Red Apple of Constantinople was popularly, but perhaps mistakenly, held to possess fabulous hoards of gold and gems. Many came who had not been summoned: volunteers and freelance raiders, hangers-on, dervishes and holy men inspired by the old prophecies who stirred the populace with words of the Prophet and the glories of martyrdom. Anatolia was on fire with excitement and remembered that ‘the promise of the Prophet foretold that that vast city … would become the abode of the people of the Faith’. Men flocked from the four corners of Anatolia – ‘from Tokat, Sivas, Kemach, Erzurum, Ganga, Bayburt and Trabzon’ – to the collecting points at Bursa; in Europe they came to Edirne. A huge force was gathering: ‘cavalry and foot soldiers, heavy infantry and archers and slingers and lancers’. At the same time, the Ottoman logistical machine swung into action, collecting, repairing and manufacturing armour, siege equipment, cannons, tents, ships, tools, weapons and food. Camel trains criss-crossed the long plateau. Ships were patched up at Gallipoli. Troops were ferried across the Bosphorus at the Throat Cutter. Intelligence was gathered from Venetian spies. No army in the world could match the Ottomans in the organization of a military campaign.

In February, troops of the European army under its leader, Karaja Bey, started to clear the hinterland of the city. Constantinople still had some fortified outposts on the Black Sea, the north shore of the Marmara and the Bosphorus. Greeks from the surrounding countryside retreated into the strongholds. Each was systematically encircled. Those that surrendered were allowed to go unharmed; others, such as those at a tower near Epibatos on the Marmara, resisted. It was stormed and the garrison slaughtered. Some could not be quickly taken; they were bypassed but kept under guard. News of these events filtered back to Constantinople and intensified the woe of the population, now riven by religious feuding. The city itself was already under careful observation by three regiments from Anatolia lest Constantine should sally out and disrupt preparations. Meanwhile the sapper

corps was at work strengthening bridges and levelling roads for the convoys of guns and heavy equipment that started to roll across the Thracian landscape in February. By March a detachment of ships from Gallipoli sailed up past the city and proceeded to ferry the bulk of the Anatolian forces into Europe. A great force was starting to converge.

Finally on 23 March Mehmet set out from Edirne in great pomp ‘with all his army, cavalry and infantry, travelling across the landscape, devastating and disturbing everything, creating fear and agony and the utmost horror wherever he went’. It was a Friday, the most holy day of the Muslim week, and carefully chosen to emphasize the sacred dimension of the campaign. He was accompanied by a notable religious presence: ‘the ulema, the sheikhs and the descendants of the Prophet … repeating prayers … moved forward with the army, and rode by the rein of the Sultan’. The cavalcade also probably included a state functionary called Tursun Bey, who was to write a rare firsthand Ottoman account of the siege. At the start of April, this formidable force converged on the city. The first of April was Easter Sunday, the most holy day in the Orthodox calendar, and it was celebrated throughout the city with a mixture of piety and apprehension. At midnight candlelight and incense proclaimed the mystery of the risen Christ in the city’s churches. The haunting and simple line of the Easter litany rose and fell over the dark city in mysterious quartertones. Bells were rung. Only St Sophia itself remained silent and unvisited by the Orthodox population. In the preceding weeks people had ‘begged God not to let the City be attacked during Holy Week’ and sought spiritual strength from their icons. The most revered of these, the Hodegetria, the miracle-working image of the Mother of God, was carried to the imperial palace at Blachernae for Easter week according to custom and tradition.

The next day Ottoman outriders were sighted beyond the walls. Constantine dispatched a sortie to confront them and in the ensuing skirmish some of the raiders were killed. As the day wore on however, ever increasing numbers of Ottoman troops appeared over the horizon and Constantine took the decision to withdraw his men into the city. All the bridges over the fosse were systematically destroyed and the gates closed. The city was sealed against whatever was to come. The sultan’s army began to form up in a sequence of well-rehearsed manoeuvres that combined caution with deep planning. On 2 April, the main force came to a halt five miles out. It was organized into constituent units and each

regiment was assigned its position. Over the next few days it moved forward in a series of staged advances that reminded watchers of the remorseless advance of ‘a river that transforms itself into a huge sea’ – a recurrent image in the chroniclers’ accounts of the incredible power and ceaseless motion of the army.

A Janissary

The preparatory work progressed with great speed. Sappers began cutting down the orchards and vineyards outside the walls to create a clean field of fire for the guns. A ditch was dug the length of the land wall and 250 yards from it, with an earth rampart in front as a protection for the guns. Latticework wooden screens were placed on top as a further shield. Behind this protective line, Mehmet moved the main army into its final position about a quarter of a mile from the land walls: ‘According to custom, the day that camp was to be made near Istanbul the army was ordered by regiment into rows. He ranged at the centre of the army around his person the white-capped Janissary archers, the Turkish and European crossbowmen, and the musketeers and cannonneers. The red-capped

azaps

were placed on his right and left, joined at the rear by the cavalry. Thus organised, the army marched in formation on Istanbul.’ Each regiment had its allotted place: the Anatolian troops on the right, in the position of honour, under their Turkish commander Ishak Pasha, assisted by Mahmut Pasha, another Christian renegade; the Christian, Balkan troops on the left under Karaja Pasha. A further large detachment under the Greek convert Zaganos Pasha were sent to build a roadway over the marshy ground at the top of the Horn and to cover the hills down to the Bosphorus, watching the activities of the Genoese settlement at Galata in the process. On the evening of 6 April, another Friday, Mehmet arrived to take up his carefully chosen position on the prominent hillock of Maltepe at the centre of his troops and opposite the portion of the walls that he considered to be the most vulnerable to attack. It was from here that his father Murat had conducted the siege of 1422.

Before the appalled gaze of the defenders on the wall, a tented city sprang up in the plain. According to one writer ‘his army seemed as numberless as grains of sand, spread … across the land from shore to shore’. Everything in an Ottoman campaign was conducted with a sense of order and hushed purpose that was all the more threatening for its quietness. ‘There is no prince’, conceded the Byzantine chronicler Chalcocondylas, ‘who has his armies and camps in better order, both in abundance of victuals and in the beautiful order they use in encamping without any confusion or embarrassment.’ Conical tents were ranged in ordered clusters, each unit with its officer’s tent at its centre and a distinctive banner flying from its principal pole. In the heart of the encampment, Mehmet’s richly embroidered red and gold pavilion had been erected with due ritual. The tent of the sultan was the visual symbol of his majesty – the image of his power and an echo of the khanate origins of the sultans as nomadic leaders. Each sultan had a ceremonial tent made at his accession; it expressed his particular kingship. Mehmet’s was sited beyond the outer reach of crossbow fire, and was by custom protected by a palisade, ditch and shields and surrounded in carefully formed concentric circles ‘as the halo encircles the moon’ by the protecting corps of his most loyal troops: ‘the best of the infantry, archers and support troops and the rest of his personal corps, which were the finest in the army’. Their injunction, on which the safety of the empire depended, was to guard the sultan like the apple of their eye.

The encampment was carefully organized. Standards and ensigns fluttered from the sea of tents: the

ak sancak

, the supreme white and gold banner of the sultan, the red banner of his household cavalry, the banners of the Janissary infantry – green and red, red and gold – the structural emblems of power and order in a medieval army. Elsewhere the watchers on the walls could make out the brightly coloured tents of the viziers and leading commanders, and the signifying hats and clothes of the different corps: the Janissaries in the distinctive white headdresses of the Bektashi order, the

azaps

in red turbans, cavalrymen in pointed turban helmets and chain-mail coats, Slavs in Balkan costumes. Watching Europeans commented on the array of men and equipment. ‘A quarter of them’, declared the Florentine merchant Giacomo Tetaldi, ‘were equipped with mail coats or leather tunics, of the others many were armed in the French manner, others in the Hungarian and others still had iron helmets, Turkish bows and crossbows.

The rest of the soldiers were without equipment apart from the fact that they had shields and scimitars – a type of Turkish sword.’ What further astonished the watchers on the walls were the vast numbers of animals. ‘Whilst conceding that these are found in greater numbers than men in military encampments, to carry supplies and food,’ noted Chalcocondylas, ‘only these people … not only take enough camels and mules with them to meet their needs, but also use them as a source of enjoyment, each one of them being eager to show the finest mules or horses or camels.’

The defenders could only survey this purposeful sea of activity with trepidation. As sunset approached the call to prayer would rise in a sinuous thread of sound above the tents from dozens of points as the muezzins called the men to prayer. Camp fires would be lit for the one meal of the day – for the Ottoman army campaigned frugally – and smoke drifted in the wind. A bare 250 yards from their citadel, they could catch the purposeful sounds of camp activity: the low murmuring of voices, the hammering of mallets, the sharpening of swords, the snorting and braying of horses, mules and camels. And far worse, they could probably make out the fainter sound of Christian worship from the European wing of the army. For an empire intent on holy war, the Ottomans ruled their vassals with remarkable tolerance: ‘although they were subjects of the Sultan, he had not compelled them to resign their Christian faith, and they could worship and pray as they wished’, Tetaldi noted. The help the Ottomans received from Christian subjects, mercenaries, converts and technical experts was a theme of repeated lament for the European chroniclers. ‘I can testify’, howled Archbishop Leonard, ‘that Greeks, Latins, Germans, Hungarians, Bohemians and men from all the Christian countries were on the side of the Turks … Oh, the wickedness of denying Christ like this!’ The vituperation was not wholly justified; many of the Christian soldiers came under duress as vassals of the sultan. ‘We had to ride forward to Stambol and help the Turks,’ remembered Michael the Janissary, recording that the alternative was death. Among those brought unwillingly to the siege was a young Orthodox Russian, Nestor-Iskander. He had been captured by an Ottoman detachment near Moldavia on the fringes of southern Russia and circumcised for conversion to Islam. When his troop reached the siege he evidently escaped into the city and wrote a lively account of the events that ensued.