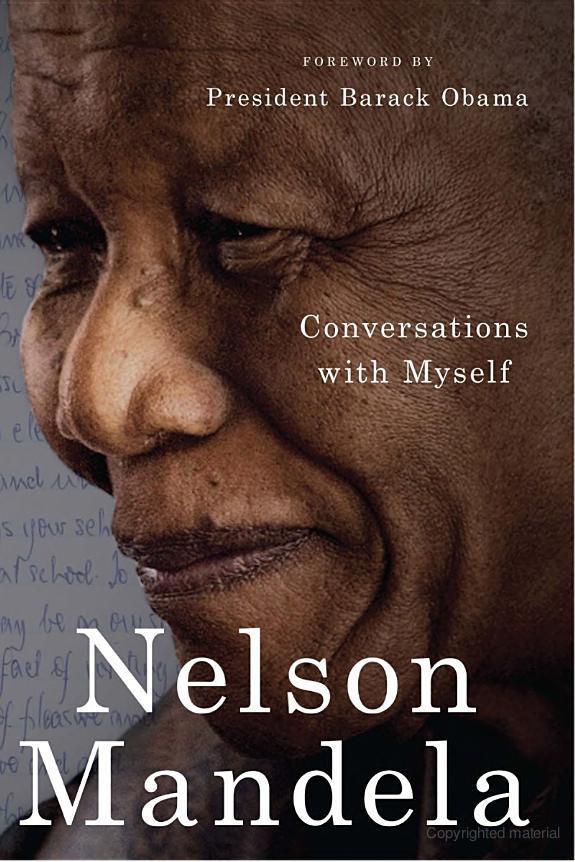

Conversations with Myself

Read Conversations with Myself Online

Authors: Nelson Mandela

For Zenani Zanethemba Nomasonto Mandela,

who passed away tragically on 11 June 2010

at the age of thirteen

…the cell is an ideal place to learn to know yourself, to search realistically and regularly the process of your own mind and feelings. In judging our progress as individuals we tend to concentrate on external factors such as one’s social position, influence and popularity, wealth and standard of education. These are, of course, important in measuring one’s success in material matters and it is perfectly understandable if many people exert themselves mainly to achieve all these. But internal factors may be even more crucial in assessing one’s development as a human being. Honesty, sincerity, simplicity, humility, pure generosity, absence of vanity, readiness to serve others – qualities which are within easy reach of every soul – are the foundation of one’s spiritual life. Development in matters of this nature is inconceivable without serious introspection, without knowing yourself, your weaknesses and mistakes. At least, if for nothing else, the cell gives you the opportunity to look daily into your entire conduct, to overcome the bad and develop whatever is good in you. Regular meditation, say about 15 minutes a day before you turn in, can be very fruitful in this regard. You may find it difficult at first to pinpoint the negative features in your life, but the 10th attempt may yield rich rewards. Never forget that a saint is a sinner who keeps on trying.

...............................................................................

From a letter to Winnie Mandela in Kroonstad Prison, dated 1 February 1975

.

Like many people around the world, I came to know of Nelson Mandela from a distance, when he was imprisoned on Robben Island. To so many of us, he was more than just a man – he was a symbol of the struggle for justice, equality, and dignity in South Africa and around the globe. His sacrifice was so great that it called upon people everywhere to do what they could on behalf of human progress.

In the most modest of ways, I was one of those people who tried to answer his call. The first time that I became politically active was during my college years, when I joined a campaign on behalf of divestment, and the effort to end apartheid in South Africa. None of the personal obstacles that I faced as a young man could compare to what the victims of apartheid experienced every day, and I could only imagine the courage that had led Mandela to occupy that prison cell for so many years. But his example helped awaken me to the wider world, and the obligation that we all have to stand up for what is right. Through his choices, Mandela made it clear that we did not have to accept the world as it is – that we could do our part to seek the world as it should be.

Over the years, I continued to watch Nelson Mandela with a sense of admiration and humility, inspired by the sense of possibility that his own life demonstrated and awed by the sacrifices necessary to achieve his dream of justice and equality. Indeed, his life tells a story that stands in direct opposition to the cynicism and hopelessness that so often afflict our world. A prisoner became a free man; a liberation figure became a passionate voice for reconciliation; a party leader became a president who advanced democracy and development. Out of formal office, Mandela continues to work for equality, opportunity and human dignity. He has done so much to change his country, and the world, that it is hard to imagine the history of the last several decades without him.

A little more than two decades after I made my first foray into political life and the divestment movement as a college student in California, I stood in Mandela’s former cell in Robben Island. I was a newly elected United States Senator. By then, the cell had been transformed from a prison to a monument to the sacrifice that was made by so many on behalf of South Africa’s peaceful transformation. Standing there in that cell, I tried to transport myself back to those days when President Mandela was still Prisoner 466/64 – a time when the success of his struggle was by no means a certainty. I tried to imagine Mandela – the legend who had changed history – as Mandela the man who had sacrificed so much for change.

Conversations with Myself

does the world an extraordinary service in giving us that picture of Mandela the man. By offering us his journals, letters, speeches, interviews, and other papers from across so many decades, it gives us a glimpse into the life that Mandela lived – from the mundane routines that helped to pass the time in prison, to the decisions that he made as President. Here, we see him as a scholar and politician; as a family man and friend; as a visionary and pragmatic leader. Mandela titled his autobiography

Long Walk to Freedom.

Now, this volume helps us recreate the different steps – as well as the detours – that he took on that journey.

By offering us this full portrait, Nelson Mandela reminds us that he has not been a perfect man. Like all of us, he has his flaws. But it is precisely those imperfections that should inspire each and every one of us. For if we are honest with ourselves, we know that we all face struggles that are large and small, personal and political – to overcome fear and doubt; to keep working when the outcome of our struggle is not certain; to forgive others and to challenge ourselves. The story within this book – and the story told by Mandela’s life – is not one of infallible human beings and inevitable triumph. It is the story of a man who was willing to risk his own life for what he believed in, and who worked hard to lead the kind of life that would make the world a better place.

In the end, that is Mandela’s message to each of us. All of us face days when it can seem like change is hard – days when our opposition and our own imperfections may tempt us to take an easier path that avoids our responsibilities to one another. Mandela faced those days as well. But even when little sunlight shined into that Robben Island cell, he could see a better future – one worthy of sacrifice. Even when faced with the temptation to seek revenge, he saw the need for reconciliation, and the triumph of principle over mere power. Even when he had earned his rest, he still sought – and seeks – to inspire his fellow men and women to service.

Prior to my election as President of the United States, I had the great privilege of meeting Mandela, and since taking office I have spoken with him occasionally by phone. The conversations are usually brief – he is in the twilight of his years, and I am faced with the busy schedule that comes with my office. But always, in those conversations, there are moments when the kindness, and generosity, and wisdom of the man shine through. Those are the moments when I am reminded that underneath the history that has been made, there is a human being who chose hope over fear – progress over the prisons of the past. And I am reminded that even as he has become a legend, to know the man – Nelson Mandela – is to respect him even more.

President Barack Obama

The name Nelson Mandela is one of the best known and most revered on earth. The person who carries that name is a hero of his age, one of the great figures in the history of the twentieth century. The story of his almost three-decade imprisonment with other political leaders of his generation has become the birth legend, or creation myth, of ‘the new South Africa’. He has become an icon. His life has been represented in countless publications, from biographies to journal articles, from feature movies to made-for-television documentaries, from coffee-table tomes to newspaper supplements, freedom songs to praise poems, institutional websites to personal blogs. But who is he,

really?

What does he

really

think?

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela himself has contributed fulsomely to the Mandela literature, publications industry and public discourse. His autobiography,

Long Walk to Freedom,

has been a best-seller since its publication in 1994. Authorised work has flowed out of his office since his release from prison in 1990. He has given thousands of interviews, speeches, recorded messages and press conferences.

Long Walk to Freedom

was fundamentally, and very deliberately, the work of a collective. The original manuscript was drafted on Robben Island by what Ahmed Kathrada – his longtime comrade, friend and fellow prisoner – describes as ‘an editorial board’. In the early 1990s Mandela worked closely with author Richard Stengel to update and expand the manuscript, with Kathrada and other advisors forming another collective overseeing the editing process. The same is true of his speeches. Aside from rare moments of improvisation, these are formal presentations of carefully prepared texts. And, not surprisingly, the preparation is usually the work of collectives. Similarly, interviewers over the years have found it almost impossible to penetrate Mandela’s very formal public persona. He is ‘the leader’, ‘the president’, ‘the public representative’, ‘the icon’. Only glimpses of the person behind the persona have shone through. The questions remain: Who is he,

really?

What does he

really

think?

* * *

Conversations with Myself

aims to give readers access to the Nelson Mandela behind the public figure, through his private archive. This archive represents Mandela writing and speaking privately, addressing either himself or his closest confidantes. This is him not geared primarily to the needs and expectations of an audience. Here he is drafting letters, speeches and memoirs. Here he is making notes (or doodling) during meetings, keeping a diary, recording his dreams, tracking his weight and blood pressure, maintaining to-do lists. Here he is meditating on his experience, interrogating his memory, conversing with a friend. Here he is not the icon or saint elevated far beyond the reach of ordinary mortals. Here he is like you and me. As he himself expresses it, ‘In real life we deal, not with gods, but with ordinary humans like ourselves: men and women who are full of contradictions, who are stable and fickle, strong and weak, famous and infamous, people in whose bloodstream the muckworm battles daily with potent pesticides.’

For most of his adult life, Mandela has been a diligent maker of records and an obsessive record-keeper. How else to explain his collection of Methodist Church membership cards recording his annual membership between 1929 and 1934? How else to explain his daily diary entries while travelling through Africa in 1962, or his habit of drafting most letters in a notebook during the prison years? Of course the archive has been ravaged by his years of struggle, of life underground, of life in prison. Records were secreted away or given to others for safe keeping. Some were lost along the way. Records were confiscated by the state, then either destroyed or used in evidence. Today the Mandela private archive is scattered and fragmentary. The single biggest accumulation is to be found in the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue. Significant collections are also held by South Africa’s National Archives, the National Intelligence Agency, the Mandela House Museum, and the Liliesleaf Trust. Myriad fragments are located in the collections of private individuals, mainly in the form of correspondence.

* * *

Conversations with Myself,

as a book project, has its origins in the 2004 inauguration of the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue as the core function of the Nelson Mandela Foundation. At the outset, the Centre’s priority was to document the scattered and fragmented ‘Mandela Archive’, but very quickly the collecting of materials not yet in archival custody became equally important. Mandela himself made his first donation of private papers to the Centre in 2004, and continued through 2009 to add to the collection. Very early on it became apparent to me as the Centre’s Memory Programme Head that an important book could be crafted from the materials, under the Centre’s purview. In 2005 a team of archivists and researchers began the painstaking work of assembling, contextualising, arranging and describing materials. Simultaneously they undertook preliminary identification and selection of items, passages and extracts that could be considered for the book. The team comprised the following members: Sello Hatang, Anthea Josias, Ruth Muller, Boniswa Nyati, Lucia Raadschelders, Zanele Riba, Razia Saleh, Sahm Venter and myself.

In 2008 I began discussing the book with publishers Geoff Blackwell and Ruth Hobday. These discussions crystallised the Centre’s thinking about the book, and introduced the project’s final phase. Mandela was briefed and gave his blessing, but indicated his wish not to be involved personally. Kathrada agreed to be the special advisor to the project. Senior Researcher Venter and Archivists Hatang, Raadschelders, Riba and Saleh were deployed under my direction as project leader for the final selection and compilation process. Crucially, historian and author Tim Couzens was drafted into the team to bring to bear both specialist expertise and the eye of a scholar not enmeshed in the Centre’s daily work. Finally, Bill Phillips – who had worked as senior editor on the

Long Walk to Freedom

project in the 1990s – came in during the project’s final editing phase.

* * *

In a real sense,

Conversations with Myself

is Nelson Mandela’s book. It gives us his own voice – direct, clear, private. But it’s important to acknowledge the editorial role played by the team. The words in this book were winnowed from a mass of material, primarily on the basis of theme, importance and immediacy, and that mass was defined by what exists and what was accessible. While we are confident that the bulk of material in Mandela’s private archive was scrutinised by the team, not everything in the custody of private individuals was located and made available to us. It was by chance, for example, that in the final months we stumbled across the archive kept by former warder Jack Swart, who was with Mandela during the last fourteen months of his incarceration in Victor Verster Prison. Also late in the game, the National Intelligence Agency disclosed to us the existence of a small Mandela collection, most of which was made available to the team. The Agency’s caginess suggests the possibility of further disclosures.

While all of the Mandela private archive was considered for this project, the final selection drew most heavily on four particular parts. Firstly: the prison letters. Some of the most poignant and painful writings are to be found in two hard-covered exercise books in which Mandela carefully drafted copies of letters he subsequently sent through the prison censors on Robben Island. They date from 1969 to 1971 and cover the very worst time of his imprisonment. Stolen from his cell by the authorities in 1971, they were returned to him by a former security policeman in 2004. Throughout his time in prison Mandela was never sure whether his correspondence would reach its destination due to the actions of what he called ‘those remorseless fates’, the censors. His prison files in the National Archives contain numerous letters the authorities wouldn’t post. They are kept together with copies they made of every letter that they did post.

Secondly: two major collections of taped conversations. Here, the spoken voice, not the written word, is heard. These encounters are so intimate, so informal, that Mandela frequently moves into reverie, enters into a dialogue with himself. The first set is about fifty hours of conversations with Richard Stengel, made when the two men were working together on

Long Walk to Freedom.

The second is a set of about twenty hours of conversations with Ahmed Kathrada, who was sentenced with Mandela and six others to life imprisonment on 12 June 1964. Kathrada was asked in the early 1990s to assist Mandela in reviewing the draft texts of both

Long Walk to Freedom

and Anthony Sampson’s authorised biography. The behind-the-scenes interaction of these two old comrades is relaxed. They are often chuckling or laughing out loud. The conversations are interesting not only for what Mandela says, but for how he says it.

Thirdly: the notebooks. Before his imprisonment in 1962, it was a habit of Mandela’s to carry a notebook. He had one with him during his journey through Africa (and to England) in 1962 to learn about revolutionary strategies, to be trained in guerrilla warfare, and to secure support from leaders of newly independent countries and nationalist movements. He had one with him when he was captured shortly after his return to South Africa. He resumed this practice in the years after his release from prison, when he was negotiating South Africa’s transition to democracy, and even, to some extent, during his presidency. These later notebooks contain notes to self,

aide-mémoire,

records of meetings and drafts of letters. There are also several extraordinary chunks of writing, each of many pages (not reproduced here for reasons of space and narrow interest), from meetings of the African National Congress Working Committee, during which he meticulously recorded the points each speaker made. Why he did this is not entirely clear. Probably it was a lawyer’s habit of carefully taking down information from his clients. Perhaps, at over seventy years of age, he felt he could not entirely trust his memory.

And fourthly: the draft of an unfinished sequel to

Long Walk to Freedom.

On 16 October 1998, he took a piece of blue notepaper and with a favoured pen he put down, in a strong and decisive hand, the date in Roman numerals. He followed this with what was his working title: ‘The Presidential Years’. Underneath it he wrote ‘Chapter One’. At some point, at the head of the page, he wrote the word ‘Draft’. The final year of his presidency, his involvement in the Burundi negotiations, political distractions of the moment, the demands of his charitable work, and an endless stream of visitors thwarted the book’s progress. His advisors suggested he get a professional writer to work with him, but he refused. He was very protective of the writing, wanting to do it himself. He did have a research assistant for a while, but he grew impatient with the arrangement. Ultimately, he simply ran out of steam.

* * *

Not surprisingly, the Mandela private archive has no inherent organising principle or system of arrangement. For

Conversations with Myself

we have grouped our selections according to an underlying rationale based partly on the chronology of Mandela’s life, and partly on the major themes of his meditations and reflections. The book comprises four parts, each with its own introduction and each carrying a title drawn from classical modes, forms and genres – pastoral, dramatic, epic and tragicomic. Mandela is steeped in the classics. He studied Latin at school and at university. He read widely in Greek literature, and acted in classics of the theatre while at university and in prison.

The book’s form is inspired most directly by Marcus Aurelius’s

Meditations,

a volume of thoughts, musings and aphorisms penned in the second century AD. Marcus Aurelius was a leader, a Roman emperor, a politician and man of action, a soldier. While not, perhaps, a great philosopher or writer, he knew the benefits of meditation, record-making and daily discipline. He wrote in the midst of action. His book is full of wisdom. Its original title translates literally as ‘To Himself’. Its attributes, and those of its author, are not entirely unrelated to those of a man and a book appearing eighteen centuries later.

Verne Harris

Project Leader

Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue

August 2010